|

Westward

Expansion 1803-1861

United States and Manifest Destiny

Westward Expansion History

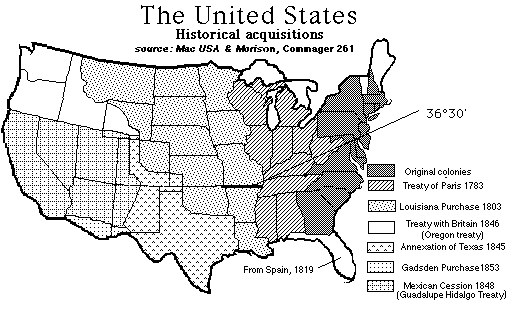

U.S. Acquisition of Land and Growth

| US Westward Expansion Map |

|

| US Westward Territory Expansion Map |

Between 1803 and 1861 the people and the institutions of the United States expanded into what is now Oklahoma

(see Manifest Destiny). This phenomenon did not take place in isolation, nor was it a sequence of random events that were of little

consequence to the basic sweep of national development. Instead, it was part of a much larger story that was programmed intentionally

by eastern centers of power to meet predetermined objectives. The agents of expansion, consequently, usually found in Oklahoma

what they were looking for exploitable natural resources, commercial opportunities, an agricultural paradise, a Great American

Desert, a resettlement zone, and a military and administrative problem. Oklahoma did

not become part of the United States until 1803, when the new American republic acquired the Louisiana Purchase. The U.S. Congress divided the purchased domain into two territories:

Orleans in the south and Louisiana in the north. The Territory of Louisiana included what is now Oklahoma and had its

administrative center at St. Louis. In 1812, northern Louisiana became the Territory of Missouri; in 1819 southern Louisiana,

including Oklahoma, was organized as the Territory of Arkansas. The territorial governors of Arkansas exercised administrative

jurisdiction over Oklahoma for the next thirty years.

President Thomas Jefferson believed that Louisiana was the stuff of empire.

For the United States, it could provide needed natural resources, living room for an expanding population, a barrier against

foreign aggression, opportunities for profitable commerce, and the space for the resettlement of eastern Indians. Jefferson

recognized, however, that effective use of Louisiana's resources required better knowledge of its people, its topography,

its flora and fauna, and its rocks and minerals. His desire for that kind of information caused him and his successors to

dispatch a series of military expeditions to undertake scientific exploration of the province once it passed into the possession

of the United States.

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark commanded the earliest and the best known

of these expeditions. Between 1804 and 1806 it gathered detailed information about the northern reaches of Louisiana, in addition

to impressing the Indians about the power and might of the Great Father in Washington. What it had done in the north, Jefferson

hoped that other expeditions would do in the south and southwest.

In 1806 the president dispatched two of these. One, led by Capt. Richard Sparks,

was to ascend Red River to the Wichita Villages and then go by horseback to the Rocky Mountains. The other, commanded by Capt.

Zebulon M. Pike, was to search out the origins of Red River by going overland to the Rockies and then south to the river.

Confronted early by units of Spanish cavalry, the Sparks expedition (also known as the Freeman-Custis expedition or Red River

expedition) aborted without achieving any of its goals. The Pike expedition, however, was more successful and heralded important

consequences for Oklahoma.

In July 1806, Pike departed from St. Louis on a route that took him up the

Missouri River to the Osage villages and then across Kansas to the Great Bend of the Arkansas River. At that point Lt. James

B. Wilkinson and five men went east down the Arkansas, while Pike and the rest of his command continued west to the Rocky

Mountains and south to an uncertain future in New Mexico. Wilkinson's route took him through Oklahoma during November and

December, where water in the river, when not frozen, was barely deep enough to float dugout canoes.

As brutal as the crossing had been, Wilkinson's report to the Jefferson administration

contributed much to the knowledge base of southern Louisiana and of Oklahoma. He established that the Osage Indians were numerous

and at war with intruder eastern tribes. He recorded that exploitable resources seemed abundant, for he had heard of lead

mines and a salt-encrusted prairie. Wilkinson also made particular note of a seven-foot waterfall on the Arkansas River (Webber

Falls).

| USA Westward Expansion Map |

|

| US Westward Expansion Map |

Nothing in Wilkinson's report intrigued government officials more than his

reference to a salt prairie, which renewed interest in long-circulating rumors about a "salt mountain." In 1811, George C.

Sibley, an Indian agent at Fort Osage, was finally able to confirm the reports when he visited the Great Salt Plains in Alfalfa

County and the Big Salt Plain in Woods County. Impressed by the vast sheets of salt that glistened "like a brilliant field

of snow" and by rocks of salt sixteen inches thick, Sibley reported that there was in northern Oklahoma an "inexhaustible

store of ready made salt" just waiting to enter "into channels of commerce."

An expedition eight years later, undertaken as a private enterprise by the

noted English botanist Thomas Nuttall, substantiated the growing sense that Oklahoma was a place of natural wonder and economic

promise. In the spring of 1819, Nuttall accompanied a military unit out of Fort Smith that followed the Poteau and Kiamichi

rivers to Red River. "Nothing," he enthused, "could exceed the beauty of these plains" with their uncommon variety of flowers,

which possessed "all the brilliancy of tropical productions."

The image of Oklahoma as portrayed by Sibley and Nuttall was dramatically

revised by reports published in the wake of a military expedition that crossed Oklahoma in the late summer 1820. Commanded

by Maj. Stephen H. Long of the Corps of Topographical Engineers, its mission was to search out once and for all the sources

of the Red and Arkansas rivers and to descend each to the Mississippi River. In June Long led his command west from Omaha

to the Rocky Mountains and then south to the headwaters of the Arkansas River. There, as had Pike before him, he divided his

column, sending Capt. John R. Bell and eleven men down the Arkansas while he continued south to the headwaters of the Red

River.

Like Wilkinson fourteen years earlier, Bell found the Arkansas route tough

going. Only this time the problem was not cold but hot temperatures. Three soldiers deserted, taking with them the journals

of zoologist Thomas Say. Bell and his remaining men were glad to reach Fort Smith on September 9, 1820. Based upon his memory

rather than his notes, Say later published an account of the expedition that described the Arkansas River valley in unenthusiastic

terms.

In the meantime, Major Long continued southward from the Arkansas, looking

for the headwaters of the Red River. His party also included a noted scientist, Edwin James. In due time, Long encountered

a broad stream which he took to be the Red River. Although cognizant of abundant wildlife, botanist James was more impressed

by the scorching, mid-August heat and the dry bed of what turned out to be the Canadian River. From his perspective, the entire

region was little more than a "wide sandy desert" and should "forever remain the unmolested haunt of the native hunter, the

bison, the prairie wolf and the marmot." Its only value to the nation was as a barrier to the "ruinous diffusion" of the American

people. James and his superior, Major Long, reached Fort Smith on September 13, embarrassed that they had explored the wrong

river but relieved that the "Great American Desert" was behind them.

| United States growth and expansion Map |

|

| Map in motion of United States growth and expansion |

Although separated by one year only, the portraits of Oklahoma as presented

by Nuttall and the military explorers were as different as night and day. One, painted in the spring, was hopeful and enthusiastic;

the other, painted in late summer, was pessimistic and apathetic. Given their time and place, both observations were probably

correct. At least for the next one hundred twenty years, however, the perception of the Long expedition prevailed in the national

consciousness. Oklahoma was part of the Great American Desert twelve months a year, an image that eastern power brokers would

use to shape its future.

While some Americans traversed Oklahoma in the interest of scientific knowledge,

others explored it in the interest of financial profit. Among the latter were the Chouteau brothers, Pierre and Auguste, as

well as Joseph Bogy, who had established profitable fur trading houses in the Three Forks region (where the Verdigris and

Neosho rivers enter the Arkansas River) at about the same time the United States acquired Louisiana. Over the next decade,

they were joined by Nathaniel Pryor, George W. Brand, Henry Barbour, Tom Slover, Hugh Love, and A. P. Chouteau. Because of

their commercial interests and activities, their collective knowledge of Oklahoma's resources and people made the "discoveries"

of Pike and Wilkinson in 1807 and Long and Bell in 1819 old news. Hunters like Alexander McFarland, who operated out of Pecan

Point on the Kiamichi River and entrepreneurs like Natchez-based Anthony Glass possessed similar knowledge regarding the Red

River. In 1808, Glass spent most of the year with the Wichita Indians at their Twin Village site trading for horses and searching

for a meteorite the tribe considered sacred.

Following the negotiation of the Adams-Onís Treaty with Spain in 1819, the activities of the Three Forks and Red River traders foreshadowed an even greater commercial, natural,

and strategic interest in Oklahoma. Among other things, the treaty set the southern and western boundary with Texas. Spain

had hoped that a clearly defined border would assure its continued possession of Mexico, but its officials miscalculated.

In 1821 the colony declared and won its independence. This unexpected development galvanized the Three Forks traders and merchants

into extraordinary commercial activity.

Assuming that new authorities in Mexico would welcome American manufactured

goods in Santa Fe, something that Spanish colonial officials had not, two notable trading expeditions left Three Forks for

New Mexico in 1821. One, led by Hugh Glenn and Jacob Fowler, was formed from residents of the Three Forks area; the other,

led by Thomas James, was organized in St. Louis. Both carried trade goods for Mexican as well as Indian customers; both were

prepared to trap for furs if the opportunity presented itself.

On the way west, the two groups took different routes. The Glenn-Flower party

followed the Arkansas River, while the James party followed the Cimarron River. With the former stopping near Pueblo, Colorado,

to trade with the Indians and to trap for beaver, only the latter enjoyed a hearty welcome in Santa Fe. It was not the first

American party, however, to set out goods in Market Square. That honor belonged to William Becknell of Franklin, Missouri,

who arrived a few days earlier by following an overland trail that cut across the Panhandle of Oklahoma. Over the next thirty

years, tens of thousands followed this Santa Fe Trail to New Mexico, including the noted Josiah Gregg.

| United States Westward Expansion Map |

|

| The nation expands westward toward Pacific Ocean |

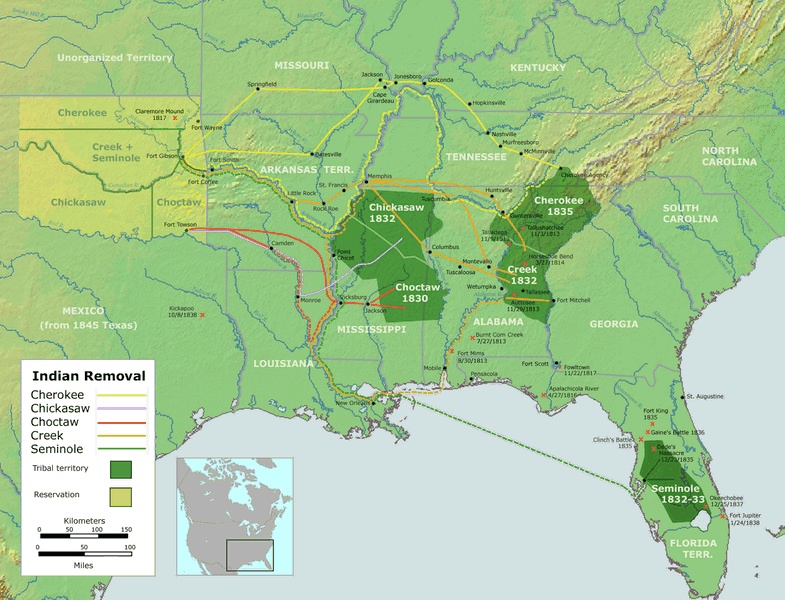

In purchasing Louisiana Territory, President Jefferson had envisioned

it as an area suitable for the relocation of American Indian people east of the Mississippi River who declined to embrace

the cultural and political sovereignty of the people and government of the United States. By 1820 this aspiration had become

settled government policy, with removal first voluntary and then mandated (Indian Removal and Trail of Tears). Government officials very early selected Oklahoma, already identified in the national psyche as marginally useful

for agriculture, as a suitable Indian Colonization Zone, or Indian Territory. No decision or event impacted Oklahoma more. Most obvious was that tens

of thousands of tribal people poured into the region.

Equally important was that the designation accelerated American expansion

into Oklahoma. Not only did the population of tribal people increase, but so too did the number of individuals and groups

who exchanged goods, provided services, and secured peace. These included commercial entrepreneurs like Holland Coffee, who

opened a trading post on Cache Creek in 1836, and Abel Warren, who operated a trading house in Love County after 1837. It

also included missionaries like Cyrus Byington, Cyrus Kingsbury, Robert Loughridge, William S. Robertson, Evan Jones, and

Joseph S. Murrow, artists like John Mix Stanley, and writers like Victor Tixier. Above all, it included the U.S. Army.

In Oklahoma, the principal role of the army was to keep the peace between

resident tribes (the Osages, Wichitas, Apaches, Comanches, and Kiowas) and emigrant tribes (Cherokees, Choctaws, Chickasaws,

Creeks, and Seminoles). Early on, the conflict between the two groups threatened to undermine the entire removal policy by

discouraging eastern emigration. To institute and enforce a peace, the army first established Fort Smith on the Arkansas River

(1817), Fort Gibson on the Neosho River (1824), and Fort Towson on the Red River (1824). As Indian removals accelerated during

the presidency of Andrew Jackson, tension between the emigrant tribes and the resident tribes, especially the Plains tribes,

increased. In 1834 the number of posts more than doubled, including Fort Coffee (on the Arkansas River), Camp Holmes (on the

Canadian River), Camp Arbuckle (in Tulsa County), and Camp Washita (on the Washita River).

The army seldom, if ever left one of these posts to do battle with a "hostile"

tribe. At the same time, commanders often dispatched troops on reconnaissance missions designed to impress all tribal groups

with the military muscle of the United States. In 1833 one such mission of Mounted Rangers out of Fort Gibson became world

famous. It included the noted American writer Washington Irving and two prominent Europeans, Charles Latrobe and Count Albert-Alexandre

de Pourtales, all three of whom wrote notable memoirs of the experience. The next year the Rangers and a new unit, the First

U.S. Dragoon Regiment, participated in an even more remarkable mission, known as the Leavenworth-Dodge Expedition.

Commanded by Gen. Henry Leavenworth and junior officers Henry Dodge, Nathan

Boone, and Jefferson Davis, the five-hundred-man expedition hoped to facilitate a peace between the Osages and the Kiowas,

Wichitas, and Comanches. The warfare between these four tribes had been a principal concern of the so-called Stokes Commission,

appointed in 1832 by President Andrew Jackson to bring peace to Indian Territory. Riding some three hundred miles southwest of Fort Gibson to the Wichita villages and

back, a journey documented ethnographically by artist George Catlin, the column met its strategic goals. Specifically, the

Comanches and Wichitas signed treaties of peace and amity with the Stokes Commission at Camp Holmes (or Mason in Cleveland

County) in 1835, and the Kiowas signed at Fort Gibson in 1837. But the mission exacted a huge price. Some 150 dragoons died

in the Oklahoma heat, including General Leavenworth.

| American Territorial Growth Map |

|

| ("From Sea to Shining Sea") |

While the army was facilitating the occupation of Oklahoma by tens of thousands

of eastern Indians, it was also marking trails and building roads utilized by both Indians and non-Indians. Among the more

important of these were local roads that connected the different forts. Some roads, however, had national significance. In

April 1849, following the discovery of gold in California, Capt. Randolph B. Marcy with the help of a trusted Delaware guide,

Black Beaver, marked a route west from Fort Smith along the south bank of the Canadian River. The next year they selected

the site for Camp Arbuckle, commissioned to protect travelers along the road. Camp Arbuckle was relocated and renamed Fort

Arbuckle in 1851. The road paralleled ones described a decade earlier (1839 and 1840) by the noted Santa Fe trader Josiah

Gregg and by the 1845 expedition that Lt. James W. Abert had led eastward from Santa Fe. Marcy's return route through Texas

and Indian Territory to Fort Smith was subsequently followed by thousands of argonauts going to the gold fields and became

the route of the Butterfield Overland Mail. In 1853, Lt. Amiel Weeks Whipple, with artist Balduin Möllhausen in his command,

traversed the same course along the 35th Parallel, reviewing it as a suitable corridor for an intercontinental railroad to

California.

The army also conducted new boundary and additional topographical surveys.

In 1850 and 1851, for example, two different expeditions that included noted naturalist S.W. Woodhouse marked the boundary

between the Creek and Cherokee Nations. In1852 Marcy systematically surveyed the sources of Red River, a goal set one-half

century earlier by President Jefferson.

By 1861, then, most of Jefferson's expectations for the Louisiana Purchase

had been realized, at least in Oklahoma. Early official and unofficial exploring parties demonstrated that it was a land of

natural beauty brimming with exploitable resources. Subsequent expeditions proved its value as a barrier to the diffusion

of the American population and to the northward expansion of Spanish influence. Three Forks and Red River traders demonstrated

that Oklahoma had commercial potential, especially in exchanges with the Osages, Wichitas, Comanches and Kiowas, but also

as a gateway to Santa Fe and even California. The successful concentration of eastern Indians illustrated the appropriateness

of Oklahoma as a resettlement zone for tribal people who did not welcome American hegemony. And the administrative and peacekeeping

activities under taken by the U.S. Army proved that colonies like Indian Territory were expensive. In all of this, Oklahoma

faithfully fulfilled the expectations of eastern centers of economic and political power, a pattern of cause and effect that

shaped the course of the state's history then and now.

(Sources listed at bottom of page.)

Recommended Reading: Seizing

Destiny: The Relentless Expansion of American Territory. From Publishers Weekly: In an admirable and important addition to his distinguished oeuvre, Pulitzer Prize–winner

Kluger (Ashes to Ashes, a history of the tobacco wars) focuses on the darker side of America's rapid expansion westward. He

begins with European settlement of the so-called New World, explaining that Britain's

successful colonization depended not so much on conquest of or friendship with the Indians, but on encouraging emigration.

Kluger then fruitfully situates the American Revolution as part of the story of expansion: the Founding Fathers based their

bid for independence on assertions about the expanse of American virgin earth and after the war that very land became the

new country's main economic resource. Continued below...

The heart of

the book, not surprisingly, covers the 19th century, lingering in detail over such well-known episodes as the Louisiana Purchase

and William Seward's acquisition of Alaska. The final chapter looks at expansion in the 20th century. Kluger

provocatively suggests that, compared with western European powers, the United States

engaged in relatively little global colonization, because the closing of the western frontier sated America's expansionist hunger. Each chapter of this long, absorbing book is rewarding

as Kluger meets the high standard set by his earlier work. Includes 10 detailed maps.

Recommended

Reading: Manifest Destiny: American Expansion and the Empire of Right (Critical Issue Book). From Booklist:

In this concise essay, Stephanson explores the religious antecedents to America's

quest to control a continent and then an empire. He interprets the two competing definitions of destiny that sprang from the

Puritans' millenarian view toward the wilderness they settled (and natives they expelled). Here was the God-given chance to

redeem the Christian world, and that sense of a special world-historical role and opportunity has never deserted the American

national self-regard. But would that role be realized in an exemplary fashion, with America

a model for liberty, or through expansionist means to create what Jefferson called "the empire

of liberty"? Continued below…

The antagonism

bubbles in two periods Stephanson examines closely, the 1840s and 1890s. In those times, the journalists, intellectuals, and

presidents he quotes wrestled with America's purpose in fighting each decade's war, which added

territory and peoples that somehow had to be reconciled with the predestined future. …A sophisticated analysis of American

exceptionalism for ruminators on the country's purpose in the world.

Recommended Reading: What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America,

1815-1848 (Oxford History of the United States)

(Hardcover: 928 pages). Review: The newest volume in

the renowned Oxford History of the United States-- A brilliant portrait of an era that saw dramatic transformations in American

life The Oxford History of the United States

is by far the most respected multi-volume history of our nation. The series includes two Pulitzer Prize winners, two New York

Times bestsellers, and winners of the Bancroft and Parkman Prizes. Now, in What Hath God Wrought, historian Daniel Walker

Howe illuminates the period from the battle of New Orleans to the end of the Mexican-American

War, an era when the United States expanded

to the Pacific and won control over the richest part of the North American continent. Continued below…

Howe's panoramic

narrative portrays revolutionary improvements in transportation and communications that accelerated the extension of the American

empire. Railroads, canals, newspapers, and the telegraph dramatically lowered travel times and spurred the spread of information.

These innovations prompted the emergence of mass political parties and stimulated America's economic development from

an overwhelmingly rural country to a diversified economy in which commerce and industry took their place alongside agriculture.

In his story, the author weaves together political and military events with social, economic, and cultural history. He examines

the rise of Andrew Jackson and his Democratic party, but contends that John Quincy Adams and other Whigs--advocates of public

education and economic integration, defenders of the rights of Indians, women, and African-Americans--were the true prophets

of America's future. He reveals the power

of religion to shape many aspects of American life during this period, including slavery and antislavery, women's rights and

other reform movements, politics, education, and literature. Howe's story of American expansion -- Manifest Destiny -- culminates

in the bitterly controversial but brilliantly executed war waged against Mexico

to gain California and Texas for the United States. By 1848, America had been transformed. What Hath God Wrought provides a monumental narrative

of this formative period in United States

history.

Recommended Reading:

The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861

(Paperback), by David M. Potter. Review: Professor

Potter treats an incredibly complicated and misinterpreted time period with unparalleled objectivity and insight. Potter masterfully

explains the climatic events that led to Southern secession – a greatly divided nation – and the Civil War: the social, political

and ideological conflicts; culture; American expansionism, sectionalism and popular sovereignty; economic and tariff

systems; and slavery. In other words, Potter places under the microscope the root causes

and origins of the Civil War. He conveys the subjects in easy to understand language to edify the reader's

understanding (it's not like reading some dry old history book). Delving

beyond surface meanings and interpretations, this book analyzes not only the history, but the historiography of the time period

as well. Continued below…

Professor Potter

rejects the historian's tendency to review the period with all the benefits of hindsight. He simply traces the events, allowing

the reader a step-by-step walk through time, the various views, and contemplates the interpretations of contemporaries and

other historians. Potter then moves forward with his analysis. The Impending Crisis is the absolute gold-standard of historical

writing… This simply is the book by which, not only other antebellum era books, but all history books should be judged.

Recommended

Reading: CAUSES OF THE CIVIL WAR: The Political, Cultural, Economic and Territorial

Disputes Between the North and South. Description: While South Carolina’s preemptive strike

on Fort Sumter and Lincoln's

subsequent call to arms started the Civil War, South Carolina's secession and Lincoln's military actions were simply the last in a chain of events stretching as far back

as 1619. Increasing moral conflicts and political debates over slavery-exacerbated by the inequities inherent between an established

agricultural society and a growing industrial one-led to a fierce sectionalism which manifested itself through cultural, economic,

political and territorial disputes. This historical study reduces sectionalism to its most fundamental form, examining the

underlying source of this antagonistic climate. From protective tariffs to the expansionist agenda, it illustrates the ways

in which the foremost issues of the time influenced relations between the North and the South.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: Brad Agnew, Fort Gibson: Terminal on the Trail of Tears (Norman:

University of Oklahoma Press, 1980). Ray Allen Billington and Martin Ridge, Westward Expansion: A History of the American

Frontier (1949; rev. ed., Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2001). Grant Foreman, Pioneer Days in the Early Southwest

(Cleveland, Ohio: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1926). William H. Goetzmann, Army Exploration in the American West, 1803-1863

(New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1959). Josiah Gregg, Commerce of the Prairies, ed. by Max L. Moorhead (Norman: University

of Oklahoma Press, 1954). Stan Hoig, Beyond the Frontier: Exploring the Indian Country (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press,

1998). Joseph A. Stout, Jr., ed., Frontier Adventurers: American Exploration in Oklahoma (Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Historical

Society, 1976).

W. David Baird

© Oklahoma Historical Society

|