|

American Civil War Prisoners of War

Union and Confederate Prisons Homepage

American Civil War POWs Homepage

Union

and Confederate Prisons and Prisoners of War

| Civil War Prisoner of War |

|

| Library of Congress |

Introduction to Civil War Prisons

The

exigencies of Civil War (1861-1865) applied to the soldier, the grunt on the battlefield, but it also extended to

the infantryman who became the prisoner of war. Union and Confederate prisons were unimaginable horror chambers employing

slow agonizing deaths to its guests. Early in the war prisoner exchanges were common, but many on both sides believed that

the war would only last 90 days. As months became years, it was obvious to Union and Confederate commanders that the

continued battlefield gridlock and stalemate had to cease. The once honored prisoner exchanges were now viewed

by Northern politicians such as Lincoln and Stanton as merely recruiting stations and reinforcements for the

dwindling Confederate military. Attrition was the answer to winning the war, was the prevailing thought of Secretary

of War Stanton. The Union Army could replace soldiers, but that was not the case in the South, so halting all exchanges

indicated that the Confederacy would soon be unable to field an army. While it was true that it spelled the final

hurrah for the men in gray, it also meant that until the war ended the Union prisoners could no longer hold to hopes

of being exchanged, but they would now have to endure prison life knowing that only their death or complete Union victory

would liberate them. Although the South continued to field an army for nearly two years after the prisoner exchanges

halted in the summer of 1863, it was not able to adequately feed and clothe its men on the march. Since Rebel soldiers marching

into the fray lacked shoes, uniforms, medicine, and food, how would Yankee prisoners fair in the Heart of Dixie? But

the Confederacy continued to plead with Washington that it was vital to resume exchanges because they could not

feed nor clothe Union prisoners. For the sake of humanity, we want for medicine, we can not feed nor clothe nor shelter

the prisoners, so for their lives will you not exchange them? By failing to resume large scale prisoner exchanges,

several thousand Union soldiers would die in Confederate prisons.

"Captain

Wirz was unjustly held responsible for the hardship and mortality of Union prisoners at Andersonville, but the Federal

authorities must share the blame for these things with the Confederacy, since they well knew the inability of the Confederates

to meet the reasonable wants of their prisoners of war, as they lacked a supply of their own needs, and since the Federal

authorities failed to exercise a humane policy in the exchange of those captured in battle." Former Andersonville prisoner-of-war Lt.

James Madison Page, Company A, 6th Michigan Cavalry. After the execution of Wirz, Page, a Union officer, who had spent

seven months as a prisoner at Andersonville, leveled unprecedented allegations against Washington, including remarks

that Wirz was merely a scapegoat, his trial was unconstitutional, and the court was filled with perjurers. He also said

that the trial was a feeble attempt by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to divert

attention away from himself, because it was Stanton's no prisoner exchange policy that killed the Union prisoners. Federal propaganda and political

cover-ups wrote Page in his 1908 best seller, The True Story of Andersonville Prison: A Defense of Major Henry Wirz,

were disingenuous efforts by Washington insiders for their halting all prisoner exchanges, which resulted in thousands

of Union men dying needlessly in Confederate prisons. Although Page had spent seven months as a prisoner at Andersonville, his

captivity and imprisonment included several months at other Confederate prisons during 1863-64.

Overview of Civil War Prisons

When the Civil War began, neither side expected a long conflict. Although

there was no formal exchange system at the beginning of the war, both armies paroled prisoners. Captured men were conditionally

released on their oath of honor not to return to battle. This allowed them to return to camps of instruction as noncombatants.

It also meant that neither side had to provide for the prisoners' needs. An exchange system set up in 1862 lasted less than

a year. North and South found themselves with thousands of prisoners of war.

The confined soldiers suffered terribly. The most common problems confronting

prisoners both North and South were overcrowding, poor sanitation, and inadequate food.

Mismanagement by prison officials, as well as by the prisoners themselves, worsened matters. The end of the war saved hundreds

of prisoners from an untimely death, but for many the war's end came too late. Of 194,732 Union soldiers held in Confederate

prison camps, some 30,000 died while captive. Union forces held about 220,000 Confederate prisoners, nearly 26,000 of whom

died. The mortality rates for some of the Civil War prison camps are shown below.

Union and Confederate Prisons and Prisoners

"We will not exchange able bodied men for

skeletons. We do not propose to reinforce the Rebel army by exchanging prisoners," Union Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton

Regarding the treatment of the Prisoner of War: “For the Northern side there is no excuse;

for the Southern side there is one--and but one. The Union prisoners were starved, as I have said before, because we were

starving ourselves; our children were crying for bread, and our Confederate soldiers were fighting on half-rations of parched

corn and peas. The North had plenty of food, clothing, and provisions, but they intentionally withheld every provision from

the Confederate prisoner… And it was done with calculated cruelty that has gone unmatched in any civilized society.”

Statistics indicate that the U.S. Government exchanged and paroled

329,963 "Rebels" and the Confederacy exchanged and paroled 152,015 "Federals." Because exchanges and paroles often occurred

on the battlefield, the soldiers were not subjected to the privations of prison. Once Total War was implemented, however, the

exchanges halted abruptly. The North had recognized that the paroled and exchanged prisoners were merely being recycled

into the Confederate army, thus prolonging what it now viewed as a war of attrition. Of 194,732 Union soldiers who were held

in Confederate prison camps, some 30,000 died in prison. While Union forces detained nearly 220,000 Confederate prisoners,

nearly 26,000 died. An exact number of deaths will never be known because of poorly kept and destroyed records.

| High Resolution Photo of Civil War Prisoners |

|

| Confederate prisoners captured in the Shenandoah Valley being guarded in a Union camp, May 1862. |

| Union Camp Chase Prison |

|

| Confederate graves at Camp Chase Cemetery |

While

the North had no shortage of troops, the South, however, could not afford to lose a single soldier. It was now simply a

war of attrition, but, on the other hand, although it favored the Union on the battlefield, it had strong ramifications for

the Federal prisoners.

Grant,

in his Memoirs, discusses why the Federal government, as late as 1863, paroled the enemy during the Civil War. On

the Confederate capitulation at Vicksburg, Grant wrote: "The enemy surrendered this morning. The only terms allowed is their

parole as prisoners of war. This I regard as a great advantage to us at this moment. It saves, probably, several days in the

capture, and leaves troops and transports ready for immediate service. Sherman, with a large force, moves immediately on Johnston,

to drive him from the State. I will send troops to the relief of Banks, and return the 9th army corps to Burnside."

At

Vicksburg alone, 31,600 prisoners were surrendered, with 172 cannon, approximately 60,000 muskets, and a large amount of ammunition.

Whole regiments were captured and paroled at Vicksburg, and most of the paroled Confederates simply reformed or mustered into

their prior (paroled) units and then returned to battle.

The

attitude of United States Secretary of War Stanton and of General Grant that no exchange so long as the North held the excess

of prisoners was a necessity of war is best seen in their own communications on the subject. On August 8, 1864, Grant sent

the following telegram to General Butler: "On the subject of exchange of prisoners, however, I differ with General Hitchcock.

It is hard on our men held in Southern prisons not to release them, but it is humanity to those left in the ranks to fight

our battles. To commence a system of exchange now, which liberates all prisoners taken, we will have to fight on until the

whole South is exterminated. If we hold those already caught, they amount to no more than so many dead men. At this particular

time to release Rebel prisoners would insure Sherman's defeat and compromise our safety here."

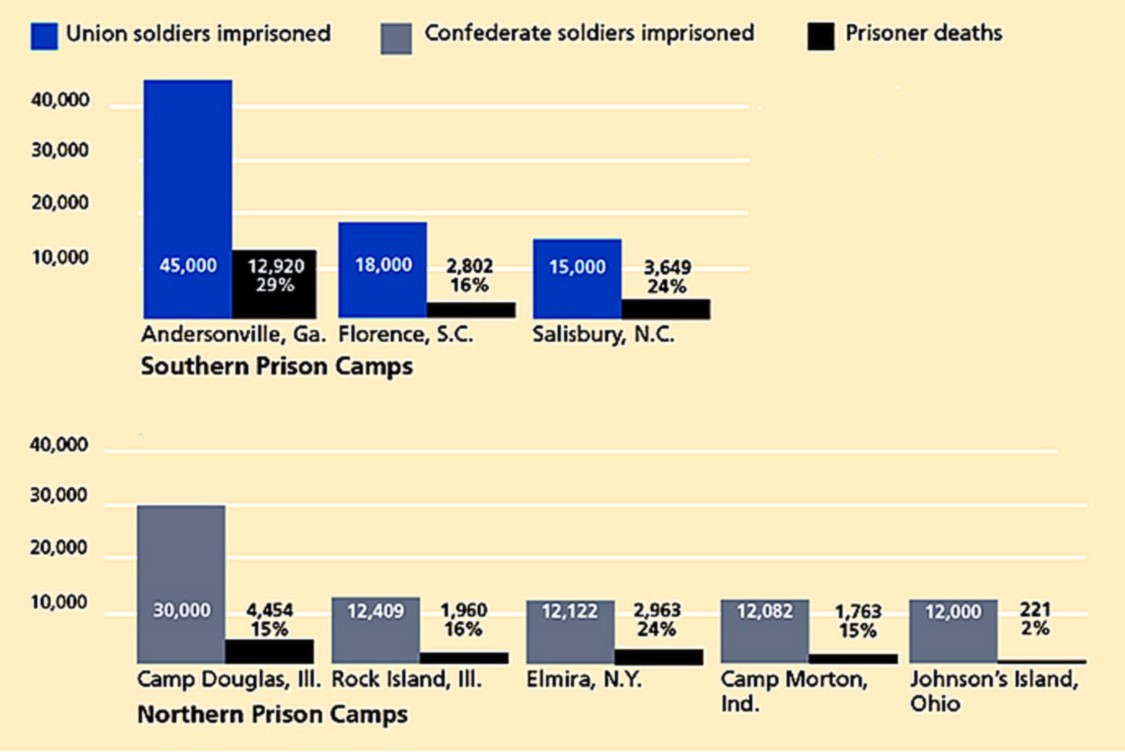

| Northern and Southern Civil War Prisons |

|

| Mortality Rates in Selected Union and Confederate Prisons |

(About) Comparison

of occupancy and mortality rates at selected Union and Confederate military prisons. National Park Service: NPS/Andersonville

National Historic Site.

| Civil War Prisoners |

|

| Civil War POWs |

"General Grant is a great general. I know him well. He stood by me

when I was crazy, and I stood by him when he was drunk; and now, sir, we stand by each other always." Words of General William

Tecumseh Sherman in 1864 regarding his successful March to the Sea

To Exchange or Not to Exchange Prisoners

of War

Grant states in his Memoirs that "the exchanged Confederate was equal on the defensive to three Union

soldiers attacking." In other words, an exchanged Confederate soldier would divert and engage three Union soldiers. Grant

simply did not want to allow and permit the South that luxury.

Stanton's words are well known: "We will not exchange able bodied men for

skeletons. We do not propose to reenforce the Rebel army by exchanging prisoners."

In a letter from Washington September

30, 1864, H. W. Halleck, major general and chief of staff, says to Major General Foster, in charge of exchange of prisoners

at Hilton Head, S C.: "Hereafter no exchange of prisoners shall be entertained except on the field when captured."

General Grant in a telegram August 21, 1864, to Secretary Stanton says: "Please

inform General Foster that under no circumstances will he be authorized to make an exchange of prisoners of war. Exchange

simply reenforces the enemy at once, while we do not get the benefit for two or three months, and lose the majority entirely.

I telegraph this from just hearing that some five or six hundred prisoners have been sent to General Foster."

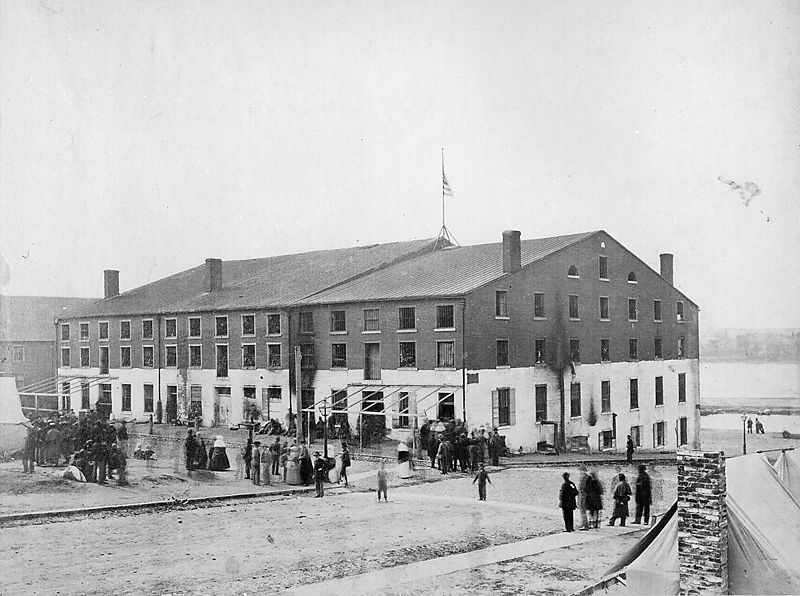

| Confederate Prisoner of War Camp Libby |

|

| Libby Prison in April 1865 |

Skeletons For Soldiers, No Thank You

On one occasion, when General Ould had effected arrangements with General

Butler for an exchange at Fortress Monroe, Grant's order that no able bodied man should be exchanged without his consent came

into effect. (General Butler stated on the floor of Congress that after he had arranged with the Confederate authorities for

an exchange of prisoners on his own terms, the whole plan was defeated by the intercession of Mr. Stanton and General Grant.

They claimed that by such an exchange Lee would get thirty thousand fresh troops, and that Grant's position at Petersburg

would be endangered and the war prolonged.) A little later Grant telegraphed to Butler to take all the sick and wounded the

Confederates would send him, but to return no more in exchange therefor.

At one time President Davis ordered General Lee to go under a flag of truce to Grant and ask in the name of humanity

that exchange of prisoners be granted, showing him how proper care of the captives was beyond control of the South. Grant

did not allow the interview, and treated everything with a deaf ear. On Lee's testimony before the Congressional Reconstruction

Committee he said: "I made several efforts to exchange the prisoners after the cartel was suspended." When his attempts at

exchange had met only with failure, General Lee reported to President Davis: "We have done everything in our power to mitigate

the suffering of prisoners, and there is no just cause for a sense of further responsibility on our part."

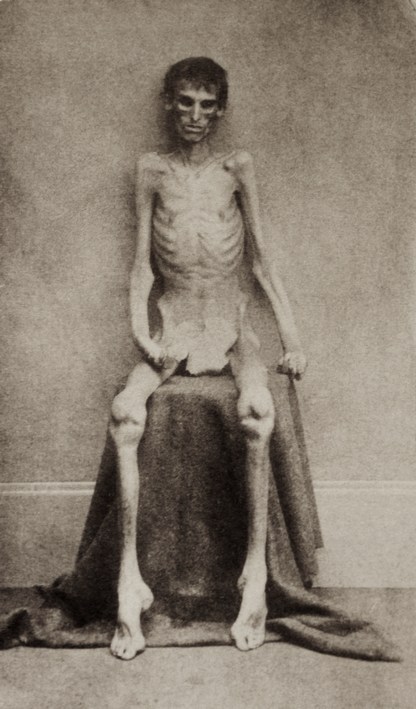

Approximately 13,000 Union prisoners died at the Confederate's Andersonville

Prison, Georgia, because of starvation, malnutrition, diarrhea, and disease. Meanwhile, Prisoner of War Camp Douglas in Chicago

was considered the “Andersonville of the North,” because of similar conditions that resulted in nearly 6,000 Confederate

deaths.

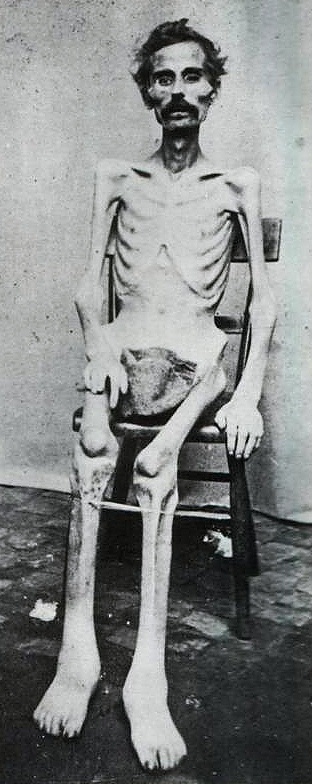

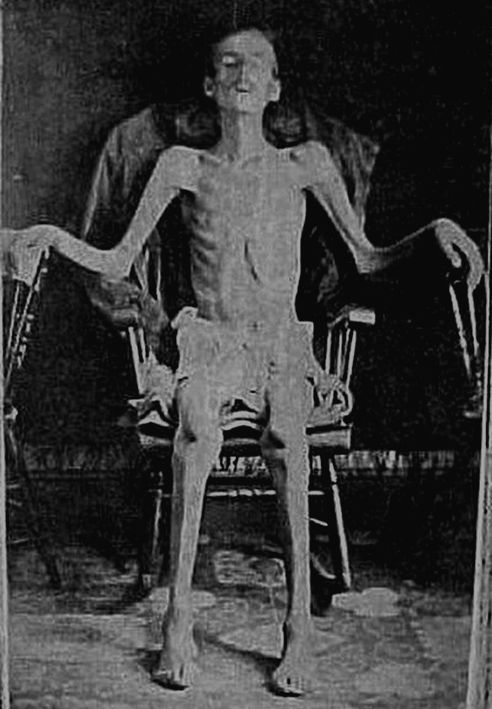

| Union and Confederate Prisoners of War |

|

| American Civil War POW |

| Civil War Prisoner |

|

| Survivor of Andersonville Prison |

Regarding prisoner exchange, during Union General Stoneman's Raid in North

Carolina in 1865, General Gillem, commanding the cavalry division, appropriated and sacked the house

of Mr. Albert Hagler. Gillem, furthermore, was especially impertinent to Mrs. Hagler, an accomplished young lady, though she

parried his attacks with the civility of a lady. On one occasion he said to her rudely, "I know you are a rebel from the way

you move--an't you a rebel?" She replied, "General Gillem, did you ever hear the story of the tailor's wife and the scissors?" "Yes." "Then I am a rebel as high as I can reach." Coarseness, however, can not always be met playfully, and Mrs. Hagler

incurred his anger to its fullest extent when, in reply to his violent denunciation of the Confederates for starving their

prisoners, she ventured to suggest that the Federal authorities might have saved all this suffering had they agreed to [prisoner]

exchange and take them North, where provisions were plenty. The General's reply to this was the giving

his men tacit license to plunder and destroy the houses of Mrs. Howard's daughter (Mrs. Hartley) and niece (Mrs. Clark), who

both lived near her. No houses in the place suffered more severely than theirs. The house of her daughter, Mrs. Hartley, was

pillaged from top to bottom. Barrels of sorghum were broken and poured over the wheat in the granary, and over the floors

of the house. Furniture and crockery were smashed, and what was not broken up was defiled in a manner so disgusting as to

be unfit for use. Mrs. Clark, the niece, was driven out of her house by the brutality of her plunderers.

Aftermath

General Grant in his "Memoirs" bluntly but honestly gives

the reason for not exchanging prisoners. It seems that it was decided at Washington that exchange meant the reinforcement

of the rebel army, and he goes on to explain that the exchanged rebel soldier behind barricades and fortifications fighting

on the defensive was equivalent to three Union soldiers attacking him. This was the Stanton policy, and if this atrocious and inhuman doctrine is anyway meritorious, the "War Secretary"

is entitled to the credit.

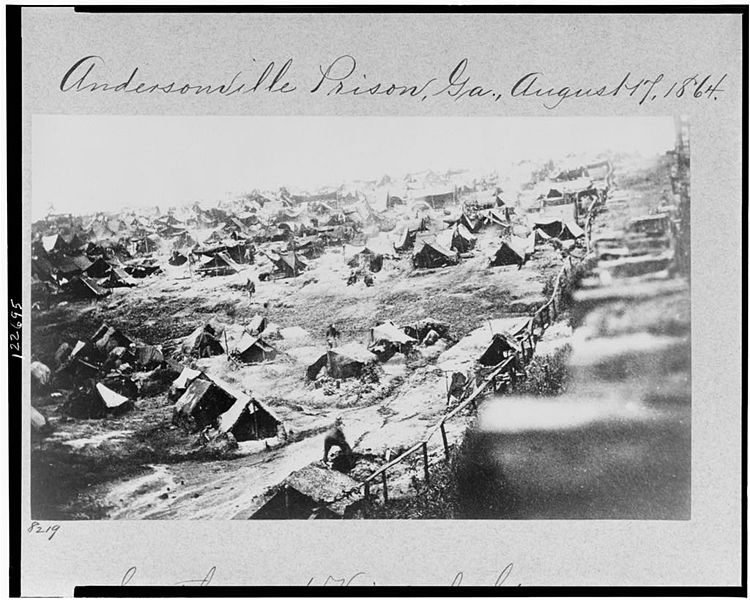

| Confederate Andersonville Prison |

|

| Andersonville Prison, August 17, 1864, with 33,000 captives. NPS |

| Union Prisoner of War Camp Elmira, NY |

|

| Confederate monument at Woodlawn National Cemetery in Elmira |

(Right) "The 100."

When A.J. Riddle took this photograph on August 17, 1864, there were nearly 33,000 Union prisoners confined within Andersonville's 26-1/2

acres. In May of '64, 708 prisoners died, but while scorching temperatures loomed during August, approximately 3,000

died -- an average of 100 prisoners per day.

"The Government held a large excess of prisoners, and the rebels

were anxious to exchange man for man; but our authorities acted upon the coldblooded theory of the Secretary of War,

that we could not afford to give well-fed, rugged men for invalids and skeletons. Those 5,000 loyal graves at Salisbury, North Carolina, will ever remain fitting monuments of

rebel cruelty and the atrocious inhumanity of Edwin M. Stanton, who steadfastly refused

to exchange prisoners. The war office at Washington preferred to let us die rather

than exchange us! The refusal upon the part of our government to exchange prisoners was now an assured fact. The sick

lost hope and died. Those in better condition physically became disheartened and sick. It is no wonder that during August,

1864, nearly 3,000 prisoners died at Andersonville." Lieut. James Madison Page, Company A, 6th Michigan Cavalry,

after spending seven months at Andersonville.

In December 1865, the New

York News printed a contrarian story that sent shockwaves across the Northern states. "Stanton wanted to treat the

populace at the North to a bloody spectacle; they believed he wanted to divert attention from his own barbarous and persistent

refusal to exchange prisoners of war; they believed he deliberately resolved to make poor Wirz the scapegoat of the iniquities

of his own Government and of himself, and to this end he violated the spirit and the letter of the military convention between

Johnston and Sherman as well as the fundamental law of the land. They believed, moreover, that the military commission before

which Wirz was tried, setting aside all decency and catching at the spirit of the Secretary of War, was overbearing and dictatorial,

and that he did not have a fair trial. And, finally, they believed the war minister of the Government, taking counsel of his

passions, his prejudices, and his hatreds, sought by the conviction and execution of Wirz to write a false chapter in the

history of the war and to infamize the South. The revulsion

of feeling in the North over the unjust execution of poor Wirz was too strong even for "the great War Secretary" to face,

and Jefferson Davis, Alex. H. Stephens, General Cobb, Josiah H. White, R. R. Stevenson, W. J. W. Kerr, Captain Reed, and last

but not least, Colonel Ould, the "Confederate Commissioner of Exchange," were never brought to trial. Therefore, poor ill-fated

Wirz must have "conspired" single-handed and alone to starve and murder Union prisoners."

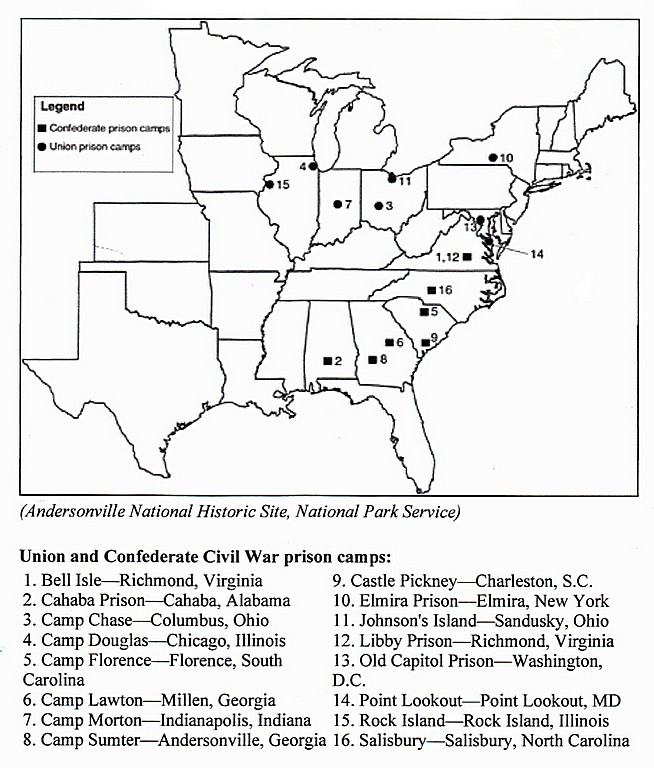

| (Map) List of Civil War Prisons |

|

| Map of Union and Confederate Prison Camps |

Common Causes of Death in the Civil War Prison

Abscess - Swollen, inflamed area in body tissues with

localized collection of pus.

Anasarca - Abnormal accumulation of fluid in tissues

and cavities of the body, resulting in swelling. Also known as dropsy.

Ascites - Accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity.

Asphyxia - Loss of consciousness due to suffocation;

inadequate oxygen, and too much carbon dioxide.

Catarrh - Inflammation of mucus membranes of nose and

throat causing increased flow of mucus. (Common cold).

Constipation - Condition in which feces are hard and

elimination is infrequent and difficult.

Diarrhea - Frequent, loose bowel movements. Symptoms

of other diseases.

Diphtheria - Acute, highly contagious disease. Characterized

by abdominal pain and intense diarrhea.

Dysentery - Various intestinal inflammations characterized

by abdominal pain and intense diarrhea.

Enteritis - Inflammation of intestines.

Erysipelas - Acute infectious disease of skin or mucus

membranes. Characterized by local inflammation and fever.

Gastritis - Inflammation of stomach.

Hemorrhoids - Painful swelling of vein in region of

the anus, often with bleeding.

Hepatitis - Inflammation of liver, often accompanied

by fever and jaundice.

Hydrocele - Accumulation of fluid in the scrotum.

Icterus - Characterized by yellowish skin, eyes, and

urine. Also known as jaundice.

Laryngitis - Inflammation of the larynx.

Nephritis - Acute or chronic disease of kidneys, characterized

by inflammation and degeneration.

Pleurisy - Inflammation of membranes covering lungs

and lining of chest cavity. Characterized by difficult and painful breathing. Also known as pleuritis.

Rubeola - Measles.

Scurvy - Disease resulting from deficiency of ascorbic

acid (Vitamin C), which is found in fresh fruits and vegetables. Characterized by weakness, spongy gums, and bleeding from

mucus membranes. Also known as scorbutus.

Smallpox - Acute, highly contagious disease. Characterized

by prolonged fever, vomiting, and pustular skin eruptions.

Tonsillitis - Inflammation of tonsils.

Typhoid - Acute infections disease, characterized by

fever and diarrhea.

Ulcus - Ulcer.

(Sources and related reading listed at bottom of page.)

Recommended

Reading: Portals to Hell: Military Prisons of the Civil War. Description: The military prisons of the Civil War, which held more than four hundred

thousand soldiers and caused the deaths of fifty-six thousand men, have been nearly forgotten. Lonnie R. Speer has now brought

to life the least-known men in the great struggle between the Union and the Confederacy, using their own words and observations as they endured a true

“hell on earth.” Continued below...

Drawing on scores of previously unpublished firsthand accounts, Portals to Hell presents the prisoners’

experiences in great detail and from an impartial perspective. The first comprehensive study of all major prisons of both

the North and the South, this chronicle analyzes the many complexities of the relationships among prisoners, guards, commandants,

and government leaders. It is available in paperback and hardcover.

Recommended Reading: So Far from Dixie: Confederates in Yankee Prisons (Hardcover) (312 pages). Description: This book is the gripping history of five men who were sent to

Elmira,

New York's infamous POW camp, and survived to document their stories. You will

hear and even envision the most stirring and gripping true stories of each soldier that lived and survived the most

horrible nightmares of the conflict while tortured and even starved as "THE PRISONER OF WAR."

Recommended Reading: To

Die in Chicago: Confederate Prisoners at Camp Douglas 1862-65 (Hardcover) (446 pages). Description: The author’s research is exacting, methodical, and painstaking.

He brought zero bias to the enterprise and the result is a stunning achievement that is both scholarly and readable. Douglas,

the "accidental" prison camp, began as a training camp for Illinois volunteers. Donalson and Island

#10 changed that. The long war that no one expected… combined with inclement weather – freezing temperatures -

primitive medical care and the barbarity of the captors created in the author’s own words "a death camp." Stanton's

and Grant's policy of halting the prisoner exchange behind the pretense of Fort

Pillow accelerated the suffering. Continued below...

In the latest

edition, Levy found the long lost hospital records at the National Archives which prove conclusively that casualties were

deliberately “under reported.” Prisoners were tortured, brutality was tolerated and corruption was widespread.

The handling of the dead rivals stories of Nazi Germany. The largest mass grave in the Western Hemisphere is filled with....the

bodies of Camp Douglas dead, 4200 known and 1800 unknown.

No one should be allowed to speak of Andersonville until they have absorbed the horror of Douglas, also known as “To

Die in Chicago.”

Recommended Reading: The True Story of Andersonville Prison:

A Defense of Major Henry Wirz. Description: During

the Civil War, James Madison Page was a prisoner in different places in the South. Seven months of that time was spent at

Andersonville. While at that prison, he

became well acquainted with Major Wirz – who had previously held the rank of captain. Page takes the stand and states

that "Captain Wirz was unjustly held responsible for the hardship and mortality of Andersonville."

It was his belief that both Federal and Confederate authorities must share culpability. Why? Continued below...

Because the Union knew the inability of the Confederacy to meet

the reasonable wants of its prisoners of war, as it lacked supplies for its own needs – particularly for its

Confederate soldiers - and since the Federal authorities failed to exercise a humane policy in the exchange of those captured

in battle... that policy was commonly referred to as prisoner exchange. The writer, "with malice toward none and charity for all", denies conscious prejudice, and makes the sincere

endeavor to put himself in the other fellow's place and make such a statement of the matter in hand as will satisfy all lovers

of truth and justice.

Editor’s Recommended

Viewing: Secrets of the Civil War (A&E) (DVD) (593 minutes).

Description: Nearly a century and half have passed since Lee surrendered at Appomattox, but the words and images created during the

Civil War still bring home the impact of the bloodiest conflict seen on American shores. Continued below…

Now, HISTORY reveals the lesser

known aspects of the civil war in 9 compelling documentaries: Tales of the Gun: Guns of the Civil War, The Lost Battle of

the Civil War, The Most Daring Mission of the Civil War, April 1865, Battlefield Detectives: The Civil War: Antietam, Battlefield

Detectives: The Civil War: Gettysburg, Battlefield Detectives: The Civil War: Shiloh, Secret Missions of the Civil War, and

Eighty Acres of Hell (aka "Douglas Prisoner of War Camp" in Chicago and "The Andersonville

of the North”). Also, with nearly 10 hours of Civil War history, this is welcome addition to school and local libraries,

as well as the Civil War buff.

Recommended Reading: This Republic

of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. Publishers

Weekly: Battle

is the dramatic centerpiece of Civil War history; this penetrating study looks instead at the somber aftermath. Historian

Faust (Mothers of Invention) notes that the Civil War introduced America

to death on an unprecedented scale and of an unnatural kind—grisly, random and often ending in an unmarked grave far

from home. Continued below...

She surveys the many ways the Civil War generation coped with the trauma: the concept of the Good Death—conscious,

composed and at peace with God; the rise of the embalming industry; the sad attempts of the bereaved to get confirmation of

a soldier's death, sometimes years after war's end; the swelling national movement to recover soldiers' remains and give them

decent burials; the intellectual quest to find meaning—or its absence—in the war's carnage. In the process, she

contends, the nation invented the modern culture of reverence for military death and used the fallen to elaborate its new

concern for individual rights. Faust exhumes a wealth of material—condolence letters, funeral sermons, ads for mourning

dresses, poems and stories from Civil War–era writers—to flesh out her lucid account. The result is an insightful,

often moving portrait of a people torn by grief.

Recommended Viewing:

Civil War Terror (History Channel) (DVD). Description: This is the largely

untold story of a war waged by secret agents and spies on both sides of the Mason Dixon Line. These are tales of hidden conspiracies

of terror that specifically targeted the civilian populations. Engineers of chemical weapons, new-fangled explosives and biological

warfare competed to topple their enemy. Continued below…

With insight from Civil War authorities,

we debunk the long-held image of a romantic and gentlemanly war. To revisit the past, we incorporate written sources, archival

photographs and newspaper headlines. Our reenactments bring to life key moments in our historical characters' lives and in

each of the horrific terrorist plots.

Recommended Viewing: The Civil War - A Film by Ken Burns. Review: The

Civil War - A Film by Ken Burns is the most successful public-television miniseries in American history. The 11-hour Civil War didn't just captivate a nation,

reteaching to us our history in narrative terms; it actually also invented a new film language taken from its creator. When

people describe documentaries using the "Ken Burns approach," its style is understood: voice-over narrators reading letters

and documents dramatically and stating the writer's name at their conclusion, fresh live footage of places juxtaposed with

still images (photographs, paintings, maps, prints), anecdotal interviews, and romantic musical scores taken from the era

he depicts. Continued below...

The Civil War uses all of these devices to evoke atmosphere and resurrect an event that many knew

only from stale history books. While Burns is a historian, a researcher, and a documentarian, he's above all a gifted storyteller,

and it's his narrative powers that give this chronicle its beauty, overwhelming emotion, and devastating horror. Using the

words of old letters, eloquently read by a variety of celebrities, the stories of historians like Shelby Foote and rare, stained

photos, Burns allows us not only to relearn and finally understand our history, but also to feel and experience it. "Hailed

as a film masterpiece and landmark in historical storytelling." "[S]hould be a requirement for every

student."

Sources:

Service: NPS; Andersonville National Historic Site; Library of Congress; National Archives; Exchange of Civil War Prisoners,

by John Broadus Mitchell, 342 Confederate Veteran, July 1911; Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant; Spencer, Cornelia

Phillips, The Last Ninety Days of the War in North Carolina, 1866; History Channel (A&E Networks);

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; Chipman, Norton P. The Horrors of Andersonville Rebel Prison. San Francisco:

Bancroft, 1891; Genoways, Ted & Hugh H. Genoways (eds.). A Perfect Picture of Hell: Eyewitness Accounts by Civil War Prisoners

from the 12th Iowa. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2001; McElroy, John. Andersonville: A Story of Rebel Military Prisons

Toledo: D.R. Locke, 1879; Ransom, John. Andersonville Diary. Auburn, NY: Author, 1881; Spencer, Ambrose, A Narrative of Andersonville.

New York: Harper, 1866; Stevenson, R. Randolph. The Southern Side, or Andersonville Prison. Baltimore: Turnbull, 1876; Voorhees,

Alfred H. The Andersonville Prison Diary of Alfred H. Voorhees. 1864.

|