|

Indian Removal and Trail of Tears

Setting the Stage

When English and European

immigrants arrived on the North American continent, they found many people whose appearance, lifestyle, and spiritual beliefs

differed from those they were familiar with. During the course of the next two centuries, their interactions varied between

cooperation and communication to conflict and warfare. The newcomers needed land for settlement, and they sought it by sale,

treaty, or force.

Between 1790 and 1830, tribes

located east of the Mississippi River, including the Cherokees, Chickasaws, Choctaws, Creeks, and Seminoles, signed many treaties

with the United States. Presidents George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and

James Madison struggled to find a balance between the obligation of the new nation to uphold its treaty commitments and the

desires of its new citizens for more land. Ultimately, the federal government was unwilling or unable to protect the Indians

from the insatiable demands of the settlers for more land.

The Louisiana Purchase added

millions of less densely populated square miles west of the Mississippi River to the United States. Thomas Jefferson suggested that the eastern American Indians might

be induced to relocate to the new territory voluntarily, to live in peace without interference from whites. A voluntary relocation

plan was enacted into law in 1824 and some Indians chose to move west.

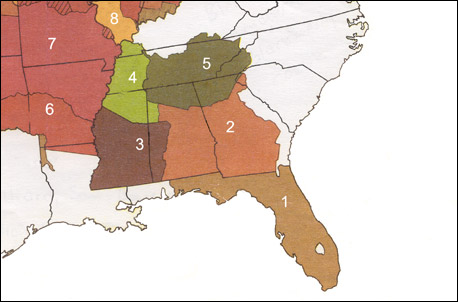

| Map of Southeastern Native American Indian Tribes |

|

| Indian Removal and Trail of Tears Map |

Land occupied by Southeastern Tribes, 1820s.

(Adapted from Sam Bowers Hilliard, "Indian Land Cessions" [detail], Map

Supplement 16, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 62, no. 2 [June 1972].)

Key:

1. Seminole

2. Creek

3. Choctaw

4. Chickasaw

5. Cherokee

6.

Quapaw

7. Osage

8. Illinois Confederation

The 1828 election of President

Andrew Jackson, who made his name as an Indian fighter, marked a change in federal policies. As part of his plans for the

United States, he was determined to remove the remaining tribes from the east and

relocate them in the west. Between the 1830 Indian Removal Act and 1850, the U.S.

government used forced treaties and/or U.S. Army action to move about 100,000 American Indians living east of the Mississippi

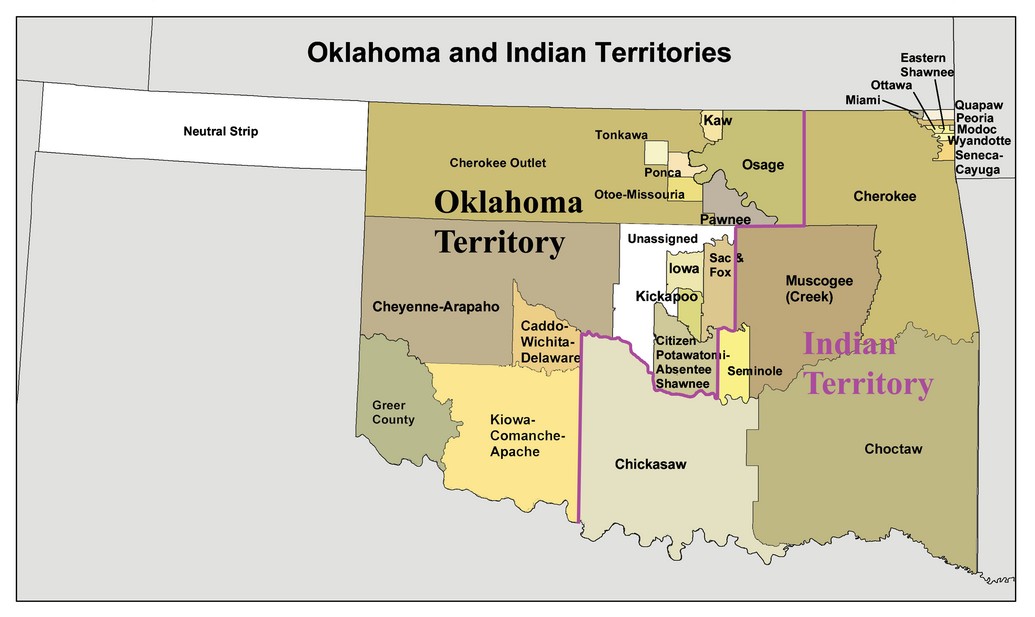

River, westward to Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma.

Among the relocated tribes were the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole. The Choctaw relocation began in 1830; the Chickasaw relocation was in 1837; the Creek were removed by force in 1836 following negotiations

that started in 1832; and the Seminole removal triggered a 7-year war that ended in 1843. The trails they followed became

known as the Trail of Tears, and the Cherokee were among the last to go and this is the

Cherokee story:

The Cherokee Nation in the 1820s

Cherokee culture thrived for thousands

of years in the southeastern United States before European contact. When the Europeans

settlers arrived, the Indians they encountered, including the Cherokee, assisted them with food and supplies. The Cherokees

taught the early settlers how to hunt, fish, and farm in their new environment. They introduced them to crops such as corn,

squash, and potatoes; and taught them how to use herbal medicines for illnesses.

By the 1820s, many Cherokees had

adopted some of the cultural patterns of the white settlers as well. The settlers introduced new crops and farming techniques.

Some Cherokee farms grew into small plantations, worked by African slaves. Cherokees built gristmills, sawmills, and blacksmith

shops. They encouraged missionaries to set up schools to educate their children in the English language. They used a syllabary

(characters representing syllables) developed by Sequoyah (a Cherokee) to encourage literacy as well. In the midst of the

many changes that followed contact with the Europeans, the Cherokee worked to retain their cultural identity operating "on

a basis of harmony, consensus, and community with a distaste for hierarchy and individual power."

In 1822, the treasurer of the

American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions reported on some of the changes that had been made:

It used to be said, a few years since, with the greatest of confidence, and is sometimes repeated

even now, that "Indians can never acquire the habit of labour." Facts abundantly disprove this opinion. Some Indians not only

provide an abundant supply of food for their families, by the labour of their own hands, but have a surplus of several hundred

bushels of corn, with which they procure clothing, furniture, and foreign articles of luxury.

Two leaders played central roles

in the destiny of the Cherokee. Both had fought alongside Andrew Jackson in a war against a faction of the Creek Nation which

became known as the Creek War (1813-1814). Both had used what they learned from the whites to become slave holders and rich

men. Both were descended from Anglo-Americans who moved into Indian territory to trade and

ended up marrying Indian women and having families. Both were fiercely committed to the welfare of the Cherokee people.

Major Ridge and John Ross shared

a vision of a strong Cherokee Nation that could maintain its separate culture and still coexist with its white neighbors.

In 1825, they worked together to create a new national capitol for their tribe, at New Echota in Georgia. In 1827, they proposed a written constitution that would put the tribe

on an equal footing with the whites in terms of self government. The constitution, which was adopted by the Cherokee National

Council, was modeled on that of the United States.

Both men were powerful speakers and well able to articulate their opposition to the constant pressure from settlers and the

federal government to relocate to the west. Ridge had first made a name for himself opposing a Cherokee proposal for removal

in 1807. In 1824 John Ross, on a delegation to Washington, D.C. wrote:

We appeal to the magnanimity of the American Congress for justice, and the protection of the

rights, liberties, and lives, of the Cherokee people. We claim it from the United

States, by the strongest obligations, which imposes it upon them by treaties; and we expect

it from them under that memorable declaration, "that all men are created equal."

Not all tribal elders or tribal

members approved of the ways in which many in the tribe had adopted white cultural practices and they sought refuge from white

interference by moving into what is now northwestern Arkansas.

In the 1820s, the numbers of Cherokees moving to Arkansas

territory increased. Others spoke out on the dangers of Cherokee participation in Christian churches, and schools, and predicted

an end to traditional practices. They believed that these accommodations to white culture would weaken the tribe's hold on

the land.

Even as Major Ridge and John Ross

were planning for the future of New Echota and an educated, well-governed tribe, the state of Georgia increased its pressure on the federal government to release Cherokee lands

for white settlement. Some settlers did not wait for approval. They simply moved in and began surveying and claiming territory

for themselves. A popular song in Georgia

at the time included this refrain:

All I ask in this creation

Is a pretty little wife and a big plantation

Way up yonder in the Cherokee Nation.

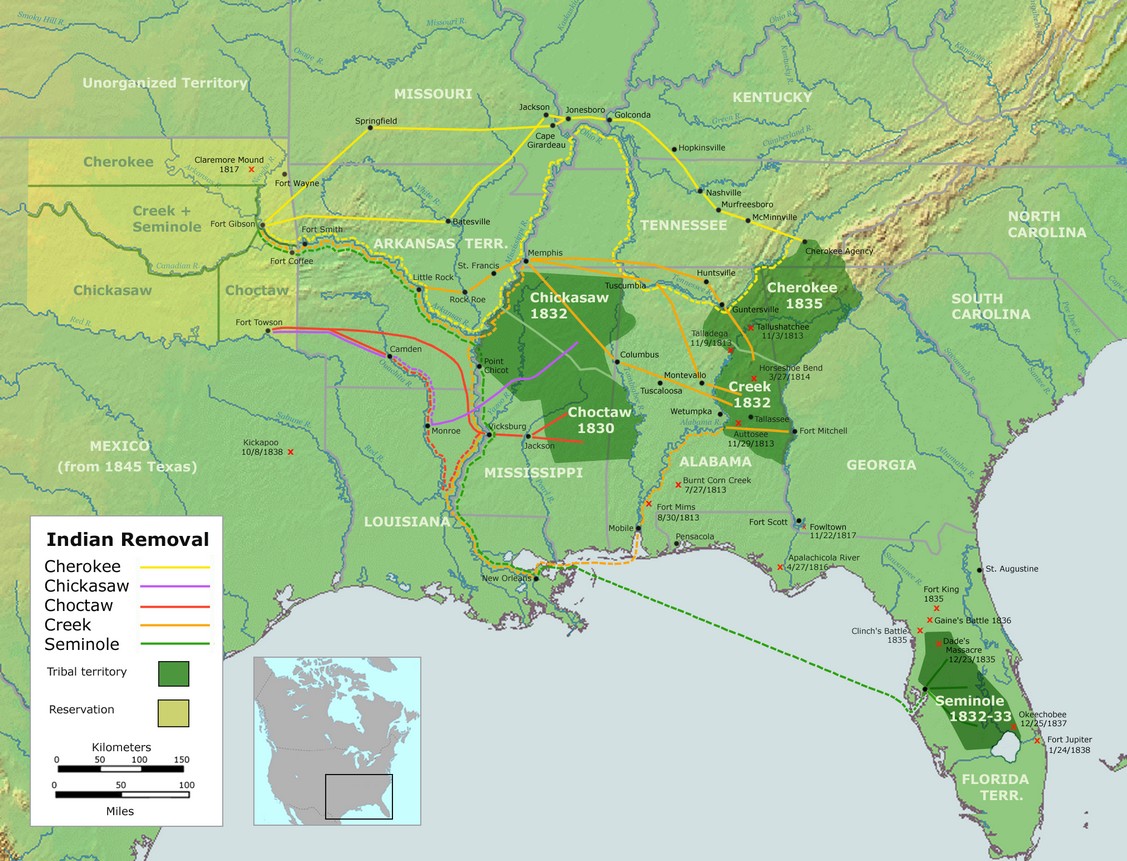

| Indian Removal and Trail of Tears Map |

|

| (Map) Indian Removal and Trail of Tears |

"You cannot remain where you now are...."

The Cherokees might have been

able to hold out against renegade settlers for a long time. But two circumstances combined to severely limit the possibility

of staying put. In 1828 Andrew Jackson became president of the United States. In 1830--the same year

the Indian Removal Act was passed--gold was found on Cherokee lands. There was no holding back the tide of Georgians, Carolinians,

Virginians, and Alabamians seeking instant wealth. Georgia

held lotteries to give Cherokee land and gold rights to whites. The state had already declared all laws of the Cherokee Nation

null and void after June 1, 1830, and also prohibited Cherokees from conducting tribal business, contracting, testifying against

whites in court, or mining for gold. Cherokee leaders successfully challenged Georgia

in the U.S. Supreme Count, but President Jackson refused to enforce the Court's decision.

Most Cherokees wanted to stay

on their land. Chief Womankiller, an old man, summed up their views:

My sun of existence is now fast approaching to its setting, and my aged bones will soon be

laid underground, and I wish them laid in the bosom of this earth we have received from our fathers who had it from the Great

Being above.

Yet some Cherokees felt that it

was futile to fight any longer. By 1832, Major Ridge, his son John, and nephews Elias Boudinot and Stand Watie had concluded

that incursions on Cherokee lands had become so severe, and abandonment by the federal government so certain, that moving

was the only way to survive as a nation. A new treaty accepting removal would at least compensate the Cherokees for their

land before they lost everything. These men organized themselves into a Treaty Party within the Cherokee community. They presented

a resolution to discuss such a treaty to the Cherokee National Council in October 1832. It was defeated. John Ross, now Principal

Chief, was the voice of the majority opposing any further cessions of land. The two men who had worked so closely together

were now bitterly divided.

The U.S. government submitted a new treaty to the Cherokee National Council in 1835.

President Jackson sent a letter outlining the treaty terms and urging its approval:

My Friends: I have long viewed your condition with great interest. For many years I have been

acquainted with your people, and under all variety of circumstances in peace and war. You are now placed in the midst of a

white population. Your peculiar customs, which regulated your intercourse with one another, have been abrogated by the great

political community among which you live; and you are now subject to the same laws which govern the other citizens of Georgia and Alabama.

I have no motive, my friends, to deceive you. I am sincerely desirous to promote your welfare.

Listen to me, therefore, while I tell you that you cannot remain where you now are. Circumstances that cannot be controlled,

and which are beyond the reach of human laws, render it impossible that you can flourish in the midst of a civilized community.

You have but one remedy within your reach. And that is, to remove to the West and join your countrymen, who are already established

there. And the sooner you do this the sooner you will commence your career of improvement and prosperity.

John Ross persuaded the council

not to approve the treaty. He continued to negotiate with the federal government, trying to strike a better bargain for the

Cherokee people. Each side--the Treaty Party and Ross's supporters--accused the other of working for personal financial gain.

Ross, however, had clearly won the passionate support of the majority of the Cherokee nation, and Cherokee resistance to removal

continued.

In December 1835, the U.S. resubmitted the treaty to a meeting of 300 to 500 Cherokees

at New Echota. Older now, Major Ridge spoke of his reasons for supporting the treaty:

I am one of the native sons of these wild woods. I have hunted the deer and turkey here, more

than fifty years. I have fought your battles, have defended your truth and honesty, and fair trading. The Georgians have shown

a grasping spirit lately; they have extended their laws, to which we are unaccustomed, which harass our braves and make the

children suffer and cry. I know the Indians have an older title than theirs. We obtained the land from the living God above.

They got their title from the British. Yet they are strong and we are weak. We are few, they are many. We cannot remain here

in safety and comfort. I know we love the graves of our fathers. We can never forget these homes, but an unbending, iron necessity

tells us we must leave them. I would willingly die to preserve them, but any forcible effort to keep them will cost us our

lands, our lives and the lives of our children. There is but one path of safety, one road to future existence as a Nation.

That path is open before you. Make a treaty of cession. Give up these lands and go over beyond the great Father of Waters.

Twenty men, none of them elected

officials of the tribe, signed the treaty, ceding all Cherokee territory east of the Mississippi

to the U.S. in exchange for $5 million and new homelands in Indian Territory. Major Ridge is reported to have said that he was signing his own death warrant.

The Treaty of New Echota was widely

protested by Cherokees and by whites. The tribal members who opposed relocation considered Major Ridge and the others who

signed the treaty traitors. After an intense debate, the U.S. Senate approved the Treaty of New Echota on May 17, 1836, by

a margin of one vote. It was signed into law on May 23. As John Ross worked to negotiate a better treaty, the Cherokees tried

to sustain some sort of normal life--even as white settlers carved up their lands and drove them from their homes. Removal

had become inevitable. It was simply a matter now of how it would be accomplished.

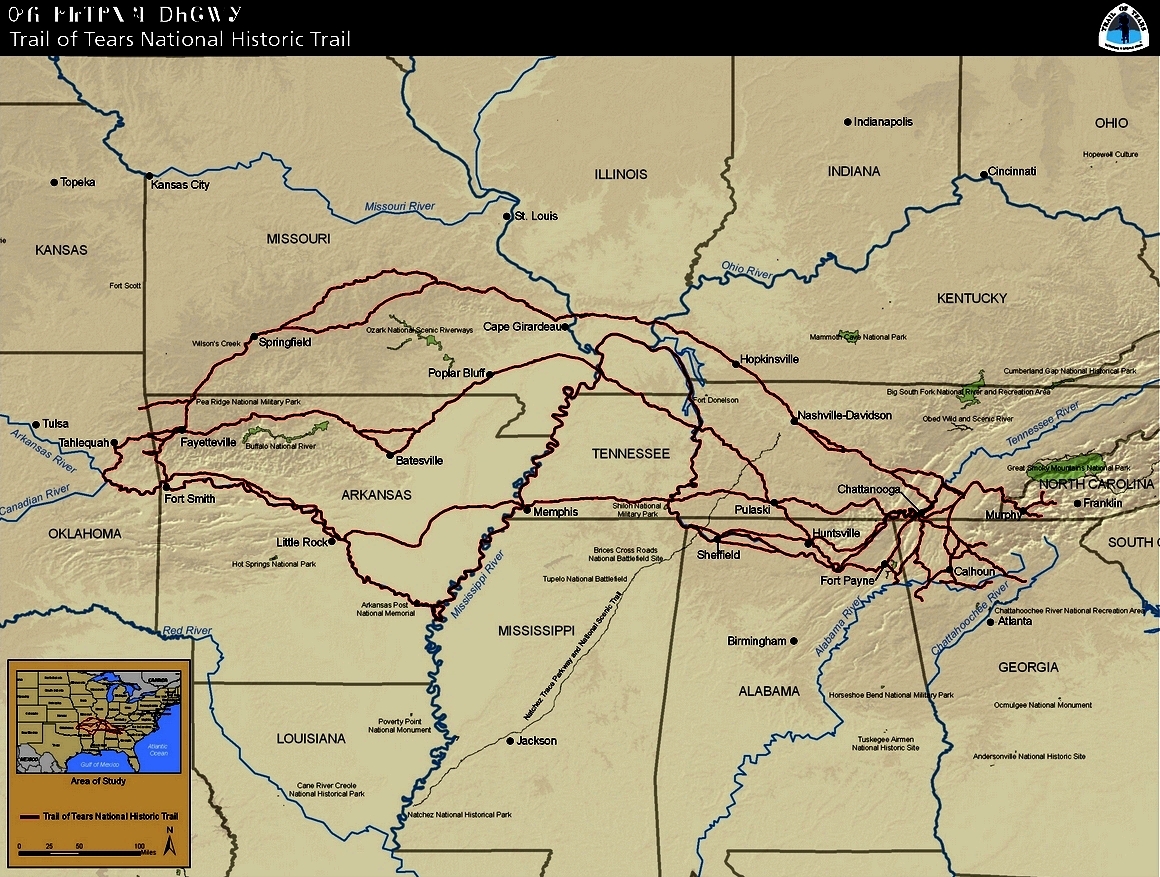

| Indian Removal and Trail of Tears Map |

|

| High Resolution Map of Indian Removal and Trail of Tears |

"Every Cherokee man, woman or child must

be in motion..."

For two years after the Treaty

of New Echota, John Ross and the Cherokees continued to seek concessions from the federal government, which remained disorganized

in its plans for removal. Only the eager settlers with their eyes on the Cherokee lands moved with determination. At the end

of December 1837, the government warned Cherokee that the clause in the Treaty of New Echota requiring that they should "remove

to their new homes within two years from the ratification of the treaty" would be enforced. In May, President Van Buren sent

Gen. Winfield Scott to get the job done. On May 10, 1838, General Scott issued the following proclamation:

Cherokees! The President of the United States has sent me, with a powerful army, to cause you, in obedience

to the Treaty of 1835, to join that part of your people who are already established in prosperity, on the other side of the

Mississippi. . . . The full moon of May is already on the

wane, and before another shall have passed away, every Cherokee man, woman and child . . . must be in motion to join their

brethren in the far West.

Federal troops and state militias

began to move the Cherokees into stockades. In spite of warnings to troops to treat them kindly, the roundup proved harrowing.

A missionary described what he found at one of the collection camps in June:

The Cherokees are nearly all prisoners. They have been dragged from their houses, and encamped

at the forts and military posts, all over the nation. In Georgia,

especially, multitudes were allowed no time to take any thing with them except the clothes they had on. Well-furnished houses

were left prey to plunderers, who, like hungry wolves, follow in the trail of the captors. These wretches rifle the houses

and strip the helpless, unoffending owners of all they have on earth.

Three groups left in the summer,

traveling from present-day Chattanooga by rail, boat, and

wagon, primarily on the water route, but as many as 15,000 people still awaited removal. Sanitation was deplorable. Food,

medicine, clothing, even coffins for the dead, were in short supply. Water was scarce and often contaminated. Diseases raged

through the camps. Many died.

Those travelling over land were

prevented from leaving in August due to a summer drought. The first detachments set forth only to find no water in the springs

and they returned back to their camps. The remaining Cherokees asked to postpone removal until the fall. The delay was granted,

provided they remain in the camps until travel resumed. The Army also granted John Ross's request that the Cherokees manage

their own removal. The government provided wagons, horses, and oxen; Ross made arrangements for food and other necessities.

In October and November, 12 detachments of 1,000 men, women, children, including more than 100 slaves, set off on an 800 mile-journey

overland to the west. Five thousand horses, and 654 wagons, each drawn by 6 horses or mules, went along. Each group was led

by a respected Cherokee leader and accompanied by a doctor, and sometimes a missionary. Those riding in the wagons were usually

only the sick, the aged, children, and nursing mothers with infants.

The northern route, chosen because

of dependable ferries over the Ohio and Mississippi

Rivers and a well-travelled road between the two rivers, turned out to

be the more difficult. Heavy autumn rains and hundreds of wagons on the muddy route made roads nearly impassable; little grazing

and game could be found to supplement meager rations. Two-thirds of the Cherokees were trapped between the ice-bound Ohio and Mississippi rivers during

January. A traveler from Maine happened upon one of the caravans in Kentucky:

We found the road literally filled with the procession for about three miles in length. The

sick and feeble were carried in waggons . . . a great many ride horseback and multitudes go on foot—even aged females,

apparently nearly ready to drop into the grave, were traveling with heavy burdens attached to the back—on the sometimes

frozen ground, and sometimes muddy streets, with no covering for the feet except what nature had given them.

A Cherokee survivor later recalled:

Long time we travel on way to new land. People feel bad when they leave Old Nation. Women cry

and made sad wails. Children cry and many men cry, and all look sad like when friends die, but they say nothing and just put

heads down and keep on go towards West. Many days pass and people die very much.

In 1972, Robert K. Thomas, a professor

of anthropology from the University of Chicago

and an elder in the Cherokee tribe, told the following story to a few friends:

Let me tell you this. My grandmother was a little girl in Georgia when the soldiers came to her house to take her family away. . . . The

soldiers were pushing her family away from their land as fast as they could. She ran back into the house before a soldier

could catch her and grabbed her [pet] goose and hid it in her apron. Her parents knew she had the goose and let her keep it.

When she had bread, she would dip a little in water and slip it to the goose in her apron.

Well, they walked a long time, you know. A long time. Some of my relatives didn't make it.

It was a bad winter and it got really cold in Illinois.

But my grandmother kept her goose alive.

One day they walked down a deep icy gulch and my grandmother could see down below her a long

white road. No one wanted to go over the road, but the soldiers made them go, so they headed across. When my grandmother and

her parents were in the middle of the road, a great black snake started hissing down the river, roaring toward the Cherokees.

The road rose up in front of her in a thunder and came down again, and when it came down all of the people in front of her

were gone, including her parents.

My grandmother said she didn't remember getting to camp that night, but she was with her aunt

and uncle. Out on the white road she had been so terrified, she squeezed her goose hard and suffocated it in her apron, but

her aunt and uncle let her keep it until she fell asleep. During the night they took it out of her apron.

On March 24, 1839, the last detachments

arrived in the west. Some of them had left their homeland on September 20, 1838. No one knows exactly how many died during

the journey. Missionary doctor Elizur Butler, who accompanied one of the detachments, estimated that nearly one fifth of the

Cherokee population died. The trip was especially hard on infants, children, and the elderly. An unknown number of slaves

also died on the Trail of Tears. The U.S.

government never paid the $5 million promised to the Cherokees in the Treaty of New Echota.

| Indian Removal and Trail of Tears Map |

|

| Indian Removal and Trail of Tears Map: From Vast Territory to Small Reservation |

(Sources listed at bottom of page)

NEW!

Recommended Viewing: We Shall Remain (PBS) (DVDs) (420 minutes). Midwest Book Review: We Shall Remain is a three-DVD thinpack set

collecting five documentaries from the acclaimed PBS history series "American Experience", about Native American leaders including

Massasoit, Tecumseh, Tenskwatawa, Major Ridge, Geronimo, and Fools Crow, all who did everything they could to resist being

forcibly removed from their land and preserve their culture. Continued below...

Their strategies

ranged from military action to diplomacy, spirituality, or even legal and political means. The stories of these individual

leaders span four hundred years; collectively, they give a portrait of an oft-overlooked yet crucial side of American history,

and carry the highest recommendation for public library as well as home DVD collections. Special features include behind-the-scenes

footage, a thirty-minute preview film, materials for educators and librarians, four ReelNative films of Native Americans sharing

their personal stories, and three Native Now films about modern-day issues facing Native Americans. 7 hours. "Viewers will

be amazed." "If you're keeping score, this program ranks among the best TV documentaries ever made." and "Reminds us that

true glory lies in the honest histories of people, not the manipulated histories of governments. This is the stuff they kept

from us." --Clif Garboden, The Boston Phoenix.

Recommended

Reading: Trail of Tears: The Rise and

Fall of the Cherokee Nation. Library

Journal: One of the many ironies of U.S. government policy toward Indians in the early 1800s is

that it persisted in removing to the West those who had most successfully adapted to European values. As whites encroached

on Cherokee land, many Native leaders responded by educating their children, learning English, and developing plantations.

Such a leader was Ridge, who had fought with Andrew Jackson against the British. Continued below...

As he and other

Cherokee leaders grappled with the issue of moving, the land-hungry Georgia legislators, with the aid of Jackson,

succeeded in ousting the Cherokee from their land, forcing them to make the arduous journey West on the infamous "Trail of

Tears." Mary B. Davis, Museum of American

Indian Lib., New York, Copyright 1988 Reed Business Information, Inc.

Recommended

Viewing: The Trail of Tears: Cherokee Legacy (2006), Starring: James Earl Jones and Wes Studi; Director: Chip Richie, Steven R. Heape.

Description: The Trail Of Tears: Cherokee Legacy is an engaging two

hour documentary exploring one of America's darkest periods in which President

Andrew Jackson's Indian Removal Act of 1830 consequently transported Native Americans of the Cherokee Nation to the bleak

and unsupportive Oklahoma Territory

in the year 1838. Deftly presented by the talents of Wes Studi (The Last of the Mohicans, Dances With Wolves, Bury My Heart

at Wounded Knee, Crazy Horse, 500 Nations, Comanche Moon), James Earl Jones, and James Garner.

Continued below...

The Trail Of

Tears: Cherokee Legacy also includes narrations of famed celebrities Crystal Gayle, Johnt Buttrum, Governor Douglas Wilder,

and Steven R. Heape. Includes numerous Cherokee Nation members which add authenticity to the production… A welcome DVD

addition to personal, school, and community library Native American history collections. The Trail Of Tears: Cherokee Legacy

is strongly recommended for its informative and tactful presentation of such a tragic and controversial historical occurrence

in 19th century American history.

Recommended

Reading: After the Trail of Tears: The Cherokees' Struggle for Sovereignty, 1839-1880. Description: This powerful narrative traces the social, cultural, and political history of the Cherokee Nation during the forty-year

period after its members were forcibly removed from the southern Appalachians and resettled in what is now Oklahoma. In this master work, completed just before his death, William McLoughlin not only

explains how the Cherokees rebuilt their lives and society, but also recounts their fight to govern themselves as a separate

nation within the borders of the United States.

Continued below...

Long regarded

by whites as one of the 'civilized tribes', the Cherokees had their own constitution (modeled after that of the United

States), elected officials, and legal system. Once re-settled, they attempted to reestablish

these institutions and continued their long struggle for self-government under their own laws—an idea that met with

bitter opposition from frontier politicians, settlers, ranchers, and business leaders. After an extremely divisive fight within

their own nation during the Civil War, Cherokees faced internal political conflicts as well as the destructive impact of an

influx of new settlers and the expansion of the railroad. McLoughlin conveys its history to the year 1880, when the nation's

fight for the right to govern itself ended in defeat at the hands of Congress.

Recommended

Reading: The Cherokee Removal:

A Brief History with Documents (The Bedford

Series in History and Culture) (Paperback). Description: This book tells the compelling story of American ethnic cleansing

against the Cherokee nation through an admirable combination of primary documents and the editors' analyses. Perdue and Green

begin with a short but sophisticated history of the Cherokee from their first interaction with Europeans to their expulsion

from the East to the West; a region where Georgia, North

Carolina, Tennessee, and Alabama

connect Continued below...

The reader

is directed through a variety of documents commenting on several important themes: the "civilizing" of the Cherokee (i.e.

their adoption of European culture), Georgia's leading role in pressuring the Cherokee off their land and demanding the federal

government to remove them by force, the national debate between promoters and opponents of expulsion, the debate within the

Cherokee nation, and a brief look at the deportation or forced removal. Conveyed in the voices of the Cherokee and the

framers of the debate, it allows the reader to appreciate the complexity of the situation. Pro-removal Americans even made

racist judgments of the Cherokee but cast and cloaked their arguments in humanitarian rhetoric. Pro-emigration Cherokee harshly

criticize the Cherokee leadership as corrupt and possessing a disdain for traditional Cherokee culture. American defenders

and the Cherokee leadership deploy legal and moral arguments in a futile effort to forestall American violence. “A compelling

and stirring read.”

Recommended Reading: The Cherokee Nation:

A History. Description:

Conley's book, "The Cherokee Nation: A History" is an eminently readable, concise but thoughtful account of the Cherokee

people from prehistoric times to the present day. The book is formatted in such a way as to make it an ideal text for high

school and college classes. At the end of each chapter is a source list and suggestions for further reading. Also at the end

of each chapter is an unusual but helpful feature- a glossary of key terms. The book contains interesting maps, photographs

and drawings, along with a list of chiefs for the various factions of the Cherokee tribe and nation. Continued below...

In addition

to being easily understood, a principal strength of the book is that the author questions some traditional beliefs and sources

about the Cherokee past without appearing to be a revisionist or an individual with an agenda in his writing. One such example

is when Conley tells the story of Alexander Cuming, an Englishman who took seven Cherokee men with him to England

in 1730. One of the Cherokee, Oukanekah, is recorded as having said to the King of England: "We look upon the Great King George

as the Sun, and as our Father, and upon ourselves as his children. For though we are red, and you are white our hands and

hearts are joined together..." Conley wonders if Oukanekah actually said those words and points out that the only version

we have of this story is the English version. There is nothing to indicate if Oukanekah spoke in English or Cherokee, or if

his words were recorded at the time they were spoken or were written down later. Conley also points out that in Cherokee culture,

the Sun was considered female, so it is curious that King George would be looked upon as the Sun. The "redness" of Native

American skin was a European perception. The Cherokee would have described themselves as brown. But Conley does not overly

dwell on these things. He continues to tell the story using the sources available. The skill of Conley in communicating his

ideas never diminishes. This book is highly recommended as a good place to start the study of Cherokee history. It serves

as excellent reference material and belongs in the library of anyone serious about the study of Native Americans.

Recommended

Viewing: The Great Indian Wars: 1540-1890 (2009) (230 minutes). Description: The year 1540 was a crucial turning point in American history. The Great

Indian Wars were incited by Francisco Vazquez de Coronado when his expedition to the Great Plains

launched the inevitable 350 year struggle between the white man and the American Indians. This series defines the struggles

of practically every major American Indian tribe. It is also a fascinating

study of the American Indians' beginnings on the North American Continent, while reflecting the factional splits as well

as alliances. Continued below...

The Great

Indian Wars is more than a documentary about the

battles and conflicts, wars and warfare, fighting tactics and strategies, and weapons of the American Indians. You will journey

with the Indians and witness how they adapted from the bow to the rifle, and view the European introduction of the horse to

the Americas and how the Indians adapted and perfected it for both hunting and

warfare. This fascinating documentary also reflects the migration patterns--including numerous maps--and the evolution

of every major tribe, as well as the strengths, weaknesses, and challenges of each tribe. Spanning nearly 4 hours and filled

with spectacular paintings and photographs, this documentary is action-packed from start to finish.

Sources: John Ehle, Trail of Tears:

The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation (New York: Doubleday, 1988), 177; D. W. Meinig, The Shaping of America: A Geographical

Perspective on 500 Years of History, Vol. 2, Continental America, 1800-1867 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 88;

Gary E. Moulton, ed., Papers of Chief John Ross, (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985), I:76-78; Baptist Missionary

Magazine 18 (Sept 1838); National Park Service; Library of Congress; 1835 Treaty of New Echota; 1830 Indian

Removal Act; Winfield Scott's Address to the Cherokee Nation, May 10, 1838; Winfield Scott's Order to U.S. Troops assigned

to the Cherokee Removal, May 17, 1838; Removal of the Indians, by Lewis Cass, January 1830; Cherokee Indian Removal Debate

U.S. Senate, April 15-17, 1830; Elias Boudinot’s editorials in The Cherokee Phoenix, 1829-31; Trail Of Tears National

Historic Trail; New Echota Historic Site; Trail of Tears Commemorative Park, Hopkinsville KY; Cherokee Nation, Oklahoma; Eastern

Band of Cherokee Indians, North Carolina; Burnett, John G. 1978 "The Cherokee Removal through the Eyes of a Private Soldier."

Journal of Cherokee Studies 3 (Summer): 180-85; Buttrick, Daniel S. 1838-39 Diary. Houghton Library, Harvard

University; Cannon, B. B. 1978 "An Overland

Journey to the West (October-December 1837)." Journal of Cherokee Studies 3 (Summer): 166-73; Deas, Lt. Edward 1978 "Emigrating

to the West by Boat (April-May 1838)." Journal of Cherokee Studies 3 (Summer): 158-63; Foreman, Grant 1932 Indian Removal

-The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press; _____. 1932 The

Five Civilized Tribes: A Brief History and a Century of Progress. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press; Henegar, H. B.

1978 "Recollections of the Cherokee Removal." Journal of Cherokee Studies 3 (Summer): 177-79; Hudson, Charles 1976 The Southeastern

Indians. Knoxville: University

of Tennessee Press; King, Duane H., and E. Raymond Evans, ed. 1978 "The

Trail of Tears: Primary Documents of the Cherokee Removal." Journal of Cherokee Studies 3 (Summer): 131-90; King, Duane H.

1988 Cherokee Heritage: Official Guidebook to the Museum of the Cherokee Indian. Cherokee, NC: Cherokee Communications; Lightfoot,

B. B. 1962 "The Cherokee Emigrants in Missouri, 1837 -1839."

Missouri Historical Review 56 (January): 156-67; Morrow, W. I. I.

1839 Diary. Western Historical Manuscript Collection, University of Missouri, Columbia; Mooney, James

1975 Historical Sketch of the Cherokee. Chicago: Aldine Publishing

Company; Moulton, Gary E. 1978 John Ross: Cherokee Chief. Athens: University of Georgia Press; Perdue, Theda

1989 The Cherokee. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. Prucha.

Francis Paul 1969 "Andrew Jackson's Indian Removal Policy: A Reassessment." Journal of American History 56 (December): 527-39;

Scott, Winfield 1978 "If Not Rejoicing at Least in Comfort." Journal of Cherokee Studies 3 (Summer): 138-42; Starr, Emmet

1921 History of the Cherokee Indians and Their Legends and Folk Lore. Oklahoma City:

The Warden Company; Thornton, Russell 1984 "Cherokee Population Losses during the Trail of Tears: A New Perspective and a

New Estimate." Ethnohistory 31 (4): 289-300. 1990 The Cherokees: A Population History. Lincoln:

University of Nebraska

Press; Wilkins, Thurman 1986 Cherokee Tragedy: The Ridge Family and the Decimation of a People. Norman:

University of Oklahoma

Press; Woodward, Grace Steele 1963 The Cherokees. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

|