|

Confederate Navy History

The Confederate

States Navy

Creation

and History of the Southern Navy

Introduction

For every ship that the Confederate Navy commissioned

during the Civil War (1861-1865), the Union produced five. Insurmountable odds would be met with innovation and ingenuity.

Many individuals often overlook

the contributions of Confederate naval services in the Civil War. The Confederate

Navy and Marine Corps, however, played significant roles in the conflict. They not

only hampered the Union Navy’s numerous missions, but took part in some of the largest battles. At the outset of

the Civil War, the Northern Navy implemented a strategy to blockade the Confederate coast from Alexandria, Virginia, to the

Rio Grande. Although initially unprepared for this daunting task, the U.S. Navy would eventually increase its fleet

to more than 600 ships and gain control of almost every port along the Southern coast and the Mississippi River. The

Union war effort benefited greatly from the implementation of General Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan.

| Confederate Navy |

|

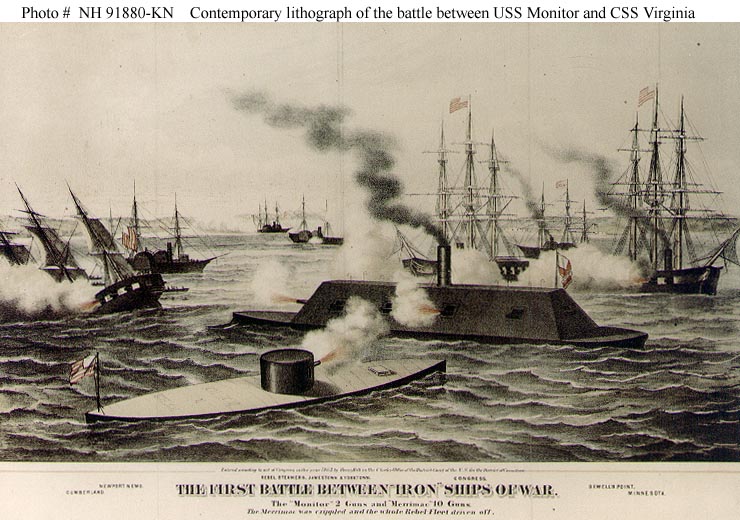

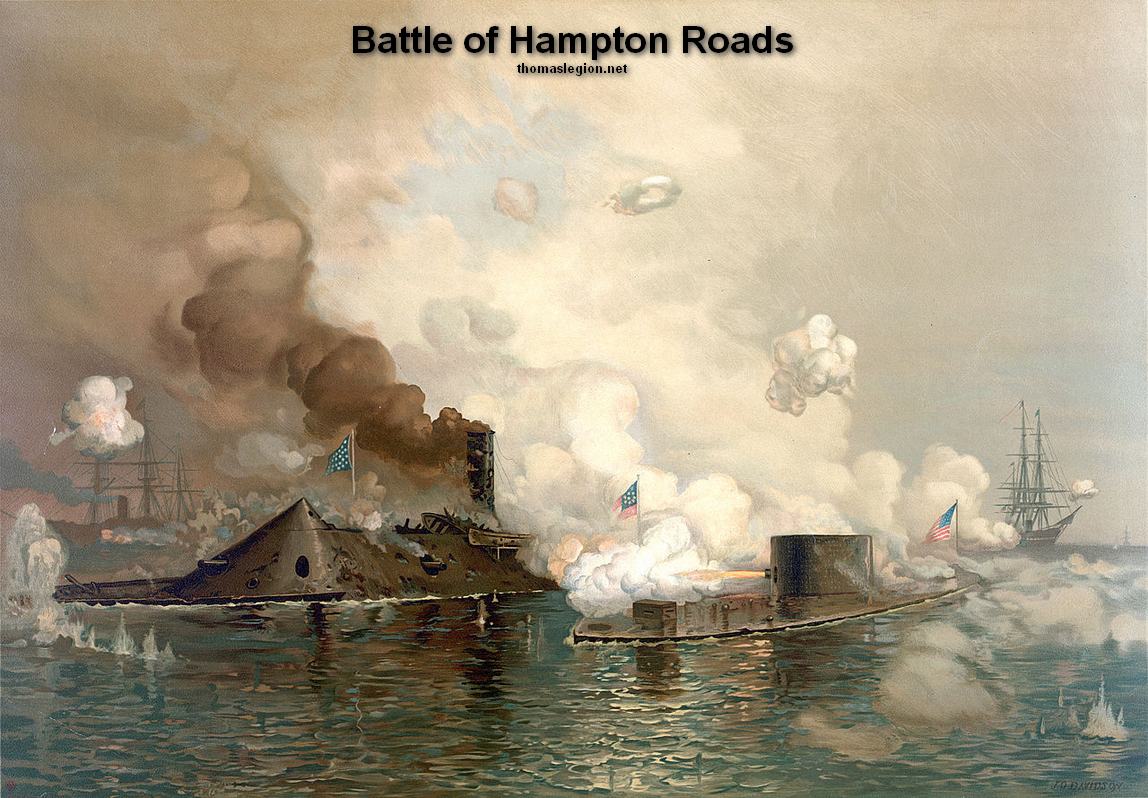

| CSS Virginia (aka Merrimack) battles Union fleet at Hampton Roads |

Creation

At Montgomery,

Alabama, the Confederate Congress created the Navy Department in February

1861. Stephen R. Mallory of Florida was selected by President

Jefferson Davis to lead the department and was confirmed by Congress on May 5. It was said

that Mallory was capable of leading the new navy due to his service on the U.S. Senate Naval Affairs Committee

prior to secession. The freshly created navy absorbed the state navies of South Carolina, Florida, Louisiana,

Texas, Alabama, Virginia,

and North Carolina. These

state navies, however, only consisted of about a dozen small ships, mounting few guns. Although by war’s end the Confederate

Navy managed to put 130 ships into service, many were not blue-water vessels but rather fitted for riverine service. The industrial

North, however, would flex its maritime muscle with an impressive 670-vessel

fleet. The disparate numbers, nevertheless, should not be considered a failure

on Mallory’s part. Whereas the Confederate Secretary of the Navy would perform well considering the circumstances,

a lack of government interest and funding throughout the war would hamper his efforts.

(Right) Example of Union manufacturing might vs. Confederate

ingenuity. CSS Virginia (aka Merrimack) sails into Hampton Roads and battles the Union fleet.

The Confederate Navy’s

mission was three-fold. First, it was to provide coastal defense and protection for

inland waterways. Second, its ironclad construction program was designed to break

the Union blockade of the southern coast. Third, it was seen as a function of the navy

to raid enemy commerce. Today, students of the Civil War remember the Confederate

Navy primarily because of the exploits of the CSS Virginia (popularly called Merrimack), CSS Alabama, and CSS Shenandoah. While the Confederate Navy was moderately successful at commerce raiding, it never

provided an adequate coastal defense or broke the Union blockade. After 1862, for instance, only three ports—Wilmington,

North Carolina; Charleston, South Carolina; and Mobile, Alabama—remained open for the Confederate blockade runners.

In

North Carolina the Confederate Navy and Marine Corps played

significant roles because much of the war in the state involved coastal operations. Early

in the war, North Carolina contributed what was nicknamed

the “Mosquito Fleet,” a small force of lightly armed vessels, to the Confederate

cause. During the 1862 Burnside Expedition in coastal North Carolina, these ships participated in

the Battle of Roanoke Island, and all but the CSS Beaufort were subsequently destroyed during the Battle of Elizabeth City. These battles ended what little threat the fleet posed to the Union forces.

Organization

From the first shots of the

Civil War through the end of 1861, 373 commissioned officers, warrant officers, and midshipmen had resigned or been dismissed

from the United States Navy and had relocated to serve the Confederacy. The Provisional Congress meeting in Montgomery

accepted these men into the Confederate Navy at their old rank. In order to accommodate them they initially provided for an

officer corps to consist of four captains, four commanders, 30 lieutenants, and various other non-line officers. On 21 April

1862, the First Congress expanded this to four admirals, ten captains, 31 commanders, 100 first lieutenants, 25 second lieutenants,

and 20 masters in line of promotion; additionally, there were to be 12 paymasters, 40 assistant paymasters, 22 surgeons, 15

passed assistant surgeons, 30 assistant surgeons, one engineer-in-chief, and 12 engineers. The act also provided for promotion

on merit: "All the Admirals, four of the Captains, five of the Commanders, twenty-two of the First Lieutenants, and five of

the Second Lieutenants, shall be appointed solely for gallant or meritorious conduct during the war."

| Confederate Navy |

|

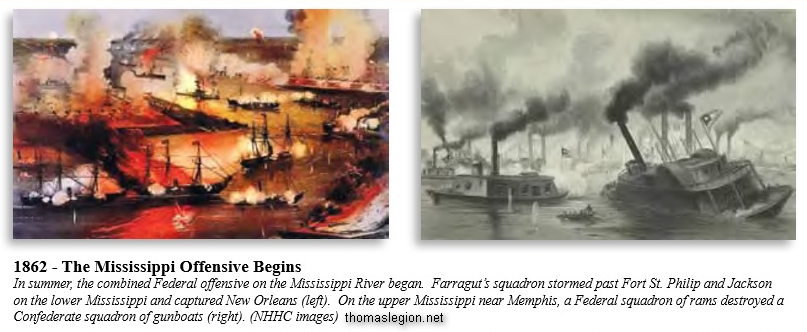

| Union and Confederate navies contest the nation's rivers and ports. |

Mission

The three major tasks of

the Confederate Navy were: the protection of Southern harbors and coastlines from invasion; making the war costly for

the United States by attacking U.S. merchant ships worldwide; and breaking the Union Blockade by luring Union warships

to make pursuit of the Confederate raiders.

History

The Confederate States Navy could never achieve equality with the numerically

superior Union Navy, so it used technological innovation, such as ironclads, submarines, torpedo boats, and naval mines (then

known as torpedoes) to gain advantage. In February 1861, the Confederate Navy had 30 vessels, only 14 of which were seaworthy.

The Union Navy began the conflict with 90 vessels, but the industrial juggernaut of the North would produce nearly 700 ships

before the war concluded. The Confederate Navy, on the other hand, eventually grew to more than 100 ships to meet and

challenge the rise in naval threats and conflicts.

On April 20, 1861, the Union was forced to quickly abandon the important

Gosport Navy Yard at Norfolk, Virginia. In their haste they failed to effectively burn the facility with its large depots

of arms and other supplies, and most of the small vessels were not scuttled. As a result, the Rebels captured much needed

war materials, including heavy cannon, gunpowder, shot, and shell. Of most importance to the newly formed Confederacy was

the shipyard 's dry docks, hardly damaged by the departing Union forces. The Confederacy 's

only substantial navy yard of note was in Pensacola, Florida, the Gulf Coast, so the Norfolk Yard was sorely needed to build

new warships and quickly confront threats on the Eastern Seaboard. The most significant warship left at the Yard was

the screw frigate USS Merrimack (often misstated as Merrimac, another Union vessel of the war).

| Confederate Navy |

|

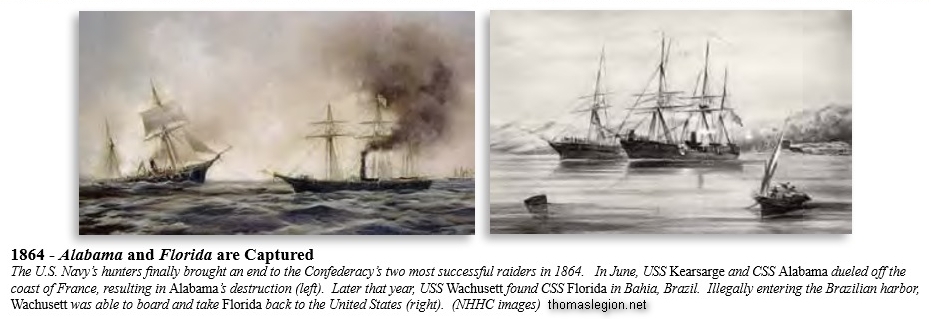

| Union Navy conducts extensive efforts to eliminate Rebel raiders. |

The U.S. Navy had torched Merrimack 's superstructure

and upper deck, then scuttled the vessel, but the fire was extinguished prior to causing irreversible damage. Little

of the ship's structure remained, however, other than the hull, which was holed by the scuttling charge but otherwise

intact. Confederate Navy Secretary Mallory had the idea to raise Merrimack and rebuild it. When the hull was raised, it had

not been submerged long enough to have been rendered unusable; the steam engines and essential machinery were salvageable.

The decks were rebuilt using thick oak and pine planking, and the upper deck was overlaid with two courses of heavy iron plate.

The newly rebuilt superstructure was unusual: above the waterline the sides sloped inward and were covered with two layers

of heavy iron-plate armor.

The vessel, predecessor to the modern battleship, was a new kind of

warship, an all-steam powered "iron-clad". In the centuries-old tradition of reusing captured ships, the new ship was christened

CSS Virginia. She soon fought the Union 's new ironclad USS Monitor to a stalemate. On the second day

of the Battle of Hampton Roads, the two iron fitted ships met and each exchanged and scored numerous hits. (On the first

day of the battle, the Virginia, and the James River Squadron, aggressively attacked and nearly broke the Union Navy 's

sea blockade of wooden warships, proving the effectiveness of the ironclad.) The two ironclads had steamed forward, tried

to outflank or ram the other, circled, backed away, and came forward firing again and again, but neither was able to sink

or demand surrender of its opponent. After four grueling hours both ships were taking in water through split seams and breaches

by enemy shot. The engines of both were becoming dangerously overtaxed, and their crews were near exhaustion. The two ships

turned and steamed away, never to meet again. This part in the Battle of Hampton Roads between Monitor and Virginia greatly

overshadowed the bloody land battles of the time. Newspapers on both side of the Mason Dixon Line were quick to print the

first battle in history between two iron-armored steam-powered warships.

It would be remiss to withhold the last surrender of a war that had claimed

some 620,000 souls. The last Confederate surrender took place in Liverpool, England, on November 6, 1865, aboard the

commerce raider CSS Shenandoah when her flag (battle ensign) was lowered for the final time. Gen. Lee had surrendered to Lt.

Gen. Grant seven months previously.

The CSS Shenandoah, built in Britain and obtained by the Confederacy in October of 1864, operated as a commerce

raider in the Atlantic, Indian, and Arctic Oceans for twelve-and-a-half months. Under the command of James Waddell, she captured

seventeen prizes—mostly whaling ships—and was en route to attack San Francisco when Waddell learned of the end

of the Civil War on land from the crew of the HMS Barracouta. The two ships encountered each other on August 2, 1865, more

than two months after the last Confederate army had surrendered. Concerned that he and his crew would be hanged as pirates

in the United States, Waddell set a course for Liverpool, England and surrendered to the British government on November 6,

1865, the last Confederates to lower their flag by a five-month margin. Waddell and his crew scattered, some making permanent

new homes in foreign nations, some returning to the United States once the threat of execution subsided. The CSS Shenandoah

was the only Confederate ship to circumnavigate the globe during the war.

| Northern Industrial Might v. Southern Ingenuity. |

|

| CSS Virginia (aka Merrimack or Merrimac) battles USS Monitor |

First

| Civil War Navy |

|

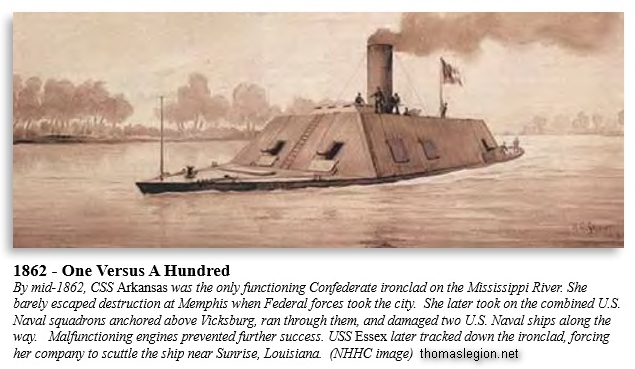

| One in a Hundred. CSS Arkansas wreaks hell on the brown water. |

The major significance of the Battle of Hampton Roads was the first combat

of ironclad warships. The Confederate fleet consisted of the ironclad ram Virginia (built from the remnants of the USS

Merrimack) and several supporting vessels. On the first day of battle, they were opposed by several conventional, wooden-hulled

ships of the Union Navy. On that day, Virginia was able to destroy two ships of the Federal flotilla, USS Congress and USS

Cumberland, and was about to attack a third, USS Minnesota, which had run aground. However, the action was halted by darkness

and falling tide, so Virginia retired to take care of her few wounded — which included her captain, Flag Officer Franklin

Buchanan — and repair her minimal battle damage. Determined to complete the destruction of the Minnesota, Catesby ap

Roger Jones, acting as captain in Buchanan's absence, returned the ship to the fray the next morning, March 9. During the

night, however, the ironclad Monitor had arrived and had taken a position to defend Minnesota. When Virginia approached, Monitor

intercepted her. The two ironclads fought for about three hours, with neither being able to inflict significant damage on

the other. The duel ended indecisively, Virginia returning to her home at the Gosport Navy Yard for repairs and strengthening,

and Monitor to her station defending Minnesota. The ships did not fight again, and the blockade remained in place. The battle

received worldwide attention, and it had immediate effects on navies around the world. The preeminent naval powers, Great

Britain and France, halted further construction of wooden-hulled ships, and others followed suit. A new type of warship was

produced, the monitor, based on the principle of the original. The use of a small number of very heavy guns, mounted so that

they could fire in all directions was first demonstrated by Monitor but soon became standard in warships of all types. Shipbuilders

also incorporated rams into the designs of warship hulls for the rest of the century.

The first successful submarine attack also occurred during the Civil War.

The H.L. Hunley, named for its inventor, Horace Hunley, put to sea in the summer of 1863. It was an eight-man submarine

armed with a bomb mounted on the end of a 22-foot pole, known as a “spar torpedo.” Seized by the Confederacy

shortly after its construction, her life was short but celebrated. She sank twice during early tests, claiming the lives

of thirteen crewmen including Hunley himself. Salvaged by persistent officers, the Hunley stole out of Charleston Harbor

on February 17, 1864 and crept towards the blockader USS Housatonic. In this, her only combat mission, she successfully sank

the Housatonic before sinking herself for reasons still unknown. Despite this perilous beginning, engineers around the world

were awakened to the potential of submarine technology, and fifty years later, 375 German “U-Boats” would unleash

havoc on the high seas.

Analysis

On the seas and on the rivers, the dueling navies of the Civil War irrevocably

shaped the fates of the armies on land and policies worldwide.

The Union navy grew by 600% to meet the demands of the war. At the outset

of the Civil War, the Federal navy was composed of around ninety ships, only around forty of which were close to combat-capable. The

central demand of Scott’s Anaconda Plan—a blockade roughly 3000 miles in length—was far beyond what the

navy was able to provide. Old ships were filled with stones and sunk in blocking positions around Southern harbors to

buy time for the engineers rushing to lay down a new fleet of warships. Hundreds

of civilian ships were pressed into service as well. Passenger ferries, their sturdy decks built to hold horse carriages,

adapted especially well to their new role as river gunboats. The Union navy grew to comprise more than six hundred ships

by 1865, the largest in the world at the time, giving the North a consistent advantage in the war on the water.

River combat played a pivotal role in the conflict—armies could

use rivers for supply routes, for fast infantry transport, and for the bombardment of enemy positions. The western theater

was particularly defined by the struggle for control of the Mississippi River, which factored as highly into the final outcome

as any other aspect of the war. Ulysses S. Grant claimed that he could not have taken the fort at Vicksburg, Mississippi

without the navy. Successful river operations demanded high-tech ironclad and steam powered fleets and led to the development

of naval strategies that are still used by the American military. In terms of the number of sailors involved and the miles

of river contested, the scale of the Civil War on “brown water” exceeds all other American wars, with Vietnam

second.

| Southern Navy History |

|

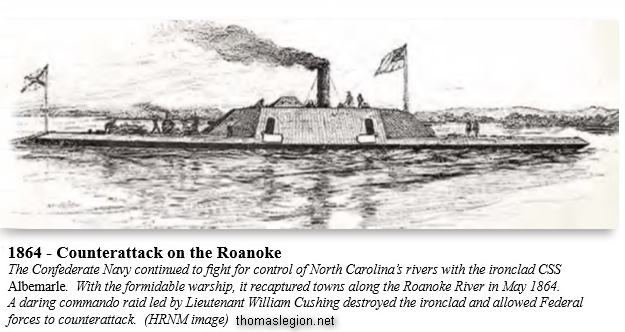

| Tenacity on the Water. CSS Albemarle sank numerous Union warships during her short career. |

Outmanned and outgunned, the Confederates engaged in asymmetrical warfare on the high seas – intercepting

Union trading ships to burn or seize their cargo. The most famous of these commerce raiders, CSS Alabama, never docked

in a Confederate port and seized over seventy vessels in the Atlantic and Pacific before she was finally defeated off the

coast of Cherbourg, France on June 19, 1864. The CSS Florida built a squadron of captured and converted ships that altogether

took sixty prizes. Confederate sailors circumnavigated the globe and some landed in ports as far-flung as Singapore, Australia,

South Africa, and Brazil. Although the Northern merchant fleet began the war with roughly 5,000 ships, many were sunk and

many more were sold to foreigners by frightened owners, reducing the total to less than 2,500 by the end of the war. This

feat was accomplished by less than twenty Confederate ships. The sensational nature of their exploits won international headlines

and more directly affected the lives of foreign populations than the war’s land battles.

Much post-war debate has been focused on the effectiveness of the Anaconda Plan and the Union blockade. One Southern

account scorns it as a “practical joke” while another claims it was a stranglehold. Considering foreign trade,

it is true that most ships that tried to get through the blockade were successful—roughly 1,000 of 1,300 foreign vessels

passed unharmed—but this fact is only part of the blockade’s larger impact. Although a total of 8,500 commercial

vessels, including domestic Southern ships, slipped into Southern ports during the war, the volume of trade was a far cry

from the 20,000 ships that docked in the years from 1856-60. The trade of cotton, the South’s largest cash crop,

plummeted by 95% during the war. Although the bravery of the blockade runners provided the Confederacy with much-needed war

materials and made gambling European merchants rich, the blockade still successfully suppressed a huge portion of the Southern

economy.

The specter of foreign intervention on the side of the Confederacy weighed heavily on Abraham Lincoln’s mind.

Events proved his concerns to be well-placed. The first crisis came in November 1861, when a Union frigate intercepted a British

mail ship, the RMS Trent, and seized two Confederate envoys that were on their way to England to lobby for intervention. In

what became known as the Trent Affair, British politicians protested the affront and began a military build-up in Canada;

American citizens called for war and even Lincoln indulged in some saber-rattling during his 1861 State of the Union Address.

Tensions eventually eased, however, when Lincoln ordered the release of the hostages without an apology.

The second crisis came when Union spies uncovered the “Laird Ram” plot in late 1862. The spies insisted,

correctly, that two ships being built in British docks for the King of Egypt--seagoing ironclads with rapid-firing revolving

turrets, altogether the most powerful ships the world had yet seen—were in reality destined for the Confederacy. Lincoln,

already greatly annoyed Britain’s unsubtle production of other warships for the South, would not stand for this potentially

balance-shifting transaction. He threatened war, forcing the British to back down and buy the ships for themselves. The awkwardness

of the issue, combined with the Civil War’s shifting tides, prompted the British to significantly decelerate their support

for the Confederacy as the war continued. Nevertheless, an international arbitration court, the first in world history,

ultimately awarded the United States 15.5 million dollars in reparations for the British contributions to the Confederate

navy. Great Britain paid, but did not admit guilt.

See also

Sources: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Records; Library of Congress; National Archives;

National Park Service.

Return to American Civil War Homepage

Best viewed with Internet Explorer or Google Chrome

google.com, pub-2111954512596717, DIRECT, f08c47fec0942fa0

|