|

Seminary Ridge

Battle of Gettysburg

Seminary Ridge Pickett’s Charge Battle of Gettysburg, Pickett’s Charge Cemetery Ridge

Battle of Gettysburg, Army of Northern Virginia Seminary Ridge, Army of the Potomac Culp's Hill Cemetery Ridge Hills

Seminary Ridge and Battle of Gettysburg

Introduction

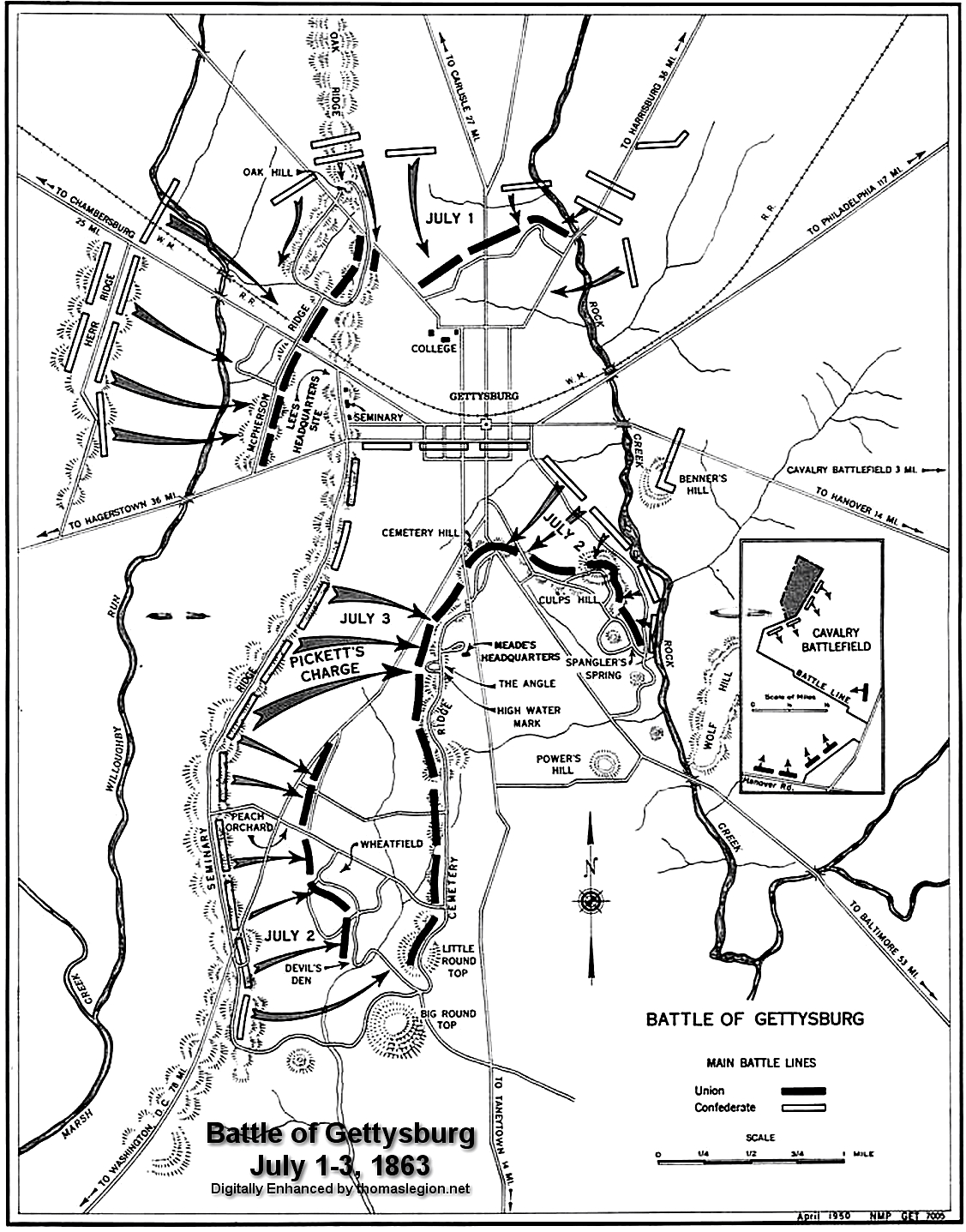

The first day of fighting at the Battle of Gettysburg (at McPherson’s Ridge, Oak Hill, Oak Ridge, Seminary Ridge, Barlow’s

Knoll and in and around the town) involved some 50,000 soldiers of which roughly 15,500 were killed, wounded, captured or

missing. The initial day in itself ranks as the 12th bloodiest battle of the Civil War. The Confederates would secure Seminary

Ridge on the 1st and then use it as a staging area for assaults on Union positions on the second and third days of the fight

at Gettysburg.

After Seminary Ridge was contested and won by the Confederates on July 1,

Gen. Robert E. Lee established his headquarters on the ridge just north of the Chambersburg pike. The ridge would now serve

as the Confederate line of battle for attacks against Union positions on Cemetery Ridge during July 2-3. As a result

of Federal artillery fire on the final day of fighting, July 3, 500 soldiers from George Pickett's division were killed or

wounded on Seminary Ridge (including 88 lost in one regiment of Kemper's Brigade).

| Seminary Ridge and Battle of Gettysburg |

|

| Seminary Ridge |

| Seminary Ridge : The Confederate batteries |

|

| Confederate batteries on Seminary Ridge |

Summary

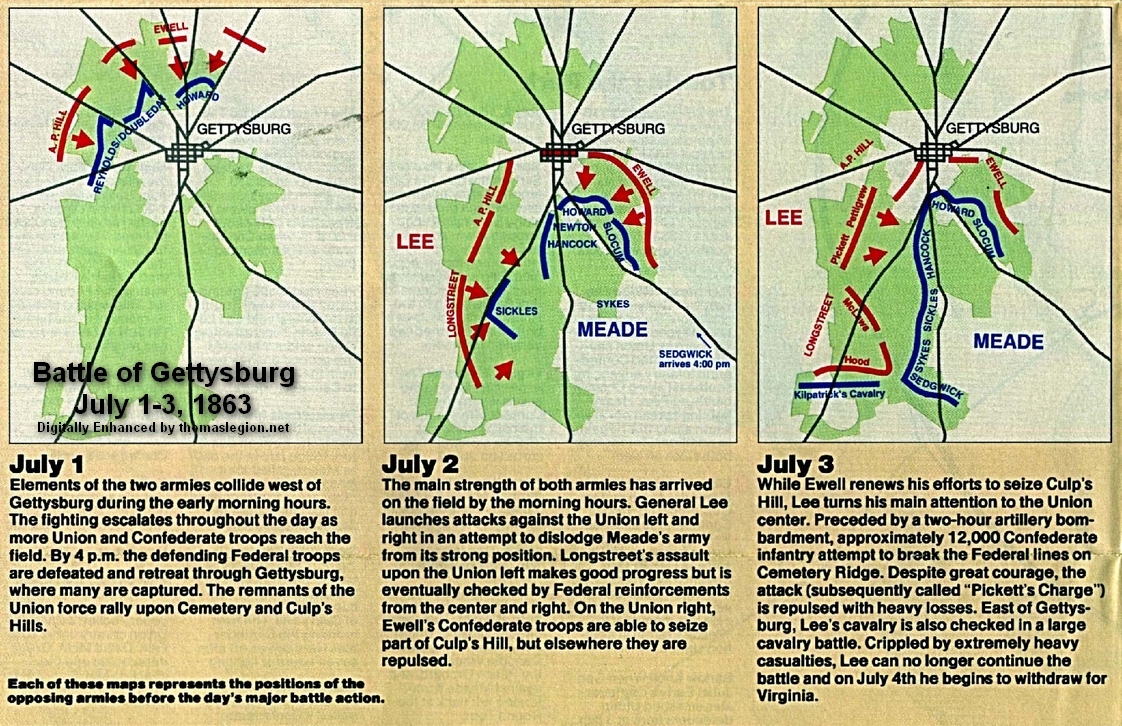

Seminary Ridge was one of the few locations on the Gettysburg battlefield that saw action each of the

three days. Having concentrated his army around the small town of Gettysburg, Gen. Robert E. Lee awaited the approach

of Union Gen. George G. Meade’s forces. On July 1, early Union success faltered as Confederates pushed back against

the Iron Brigade and exploited a weak Federal line at Barlow’s Knoll. The following day saw Lee strike the Union flanks,

leading to heavy battle at Devil's Den, Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, Peach Orchard, Culp’s Hill and East Cemetery

Hill. Southerners captured Devil’s Den and the Peach Orchard, but ultimately failed to dislodge the Union defenders.

On the final day, July 3rd, fighting raged at Culp’s Hill with the Union regaining its lost ground. After being cut

down by a massive artillery bombardment in the afternoon, Lee attacked the Union center on Cemetery Ridge and was repulsed

in what is now known as Pickett’s Charge. Lee's second invasion of the North had failed, and had resulted in heavy casualties;

an estimated 51,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, captured, or listed as missing after Gettysburg.

After it was secured on the first day, Seminary Ridge became the primary Confederate position west of Gettysburg

for the final two days of the battle. Named for the Lutheran Theological Seminary that overlooks Gettysburg from its northern

point, the ridge runs southward to the Millerstown Road where it becomes Warfield Ridge. This latter ridge extends further southward, turns to the southeast and intersects the Emmitsburg Road. For

General Lee, this ridge offered him high ground for observation of the distant Union line and an excellent artillery position

to bombard Union positions on Cemetery Hill. Seminary Ridge also offered his troops cover from prying Union eyes, acting as a barrier for him to shift his

troops north, south, or against the Union line. On the evening of July 1st, General A. P. Hill aligned the tired infantrymen

of his corps along this ridge and these troops occupied it throughout the remainder of the battle. The guns in this photograph

stand in an area south of the McMillan Farm. Infantry fighting did not extend up to this location on July 2, but batteries

here supported the Confederate attack on Cemetery Ridge, approximately one mile distant.

(Right) Tree cover on Seminary Ridge concealed Confederate troops and artillery

from view until the attack began. Photo Gettysburg NMP.

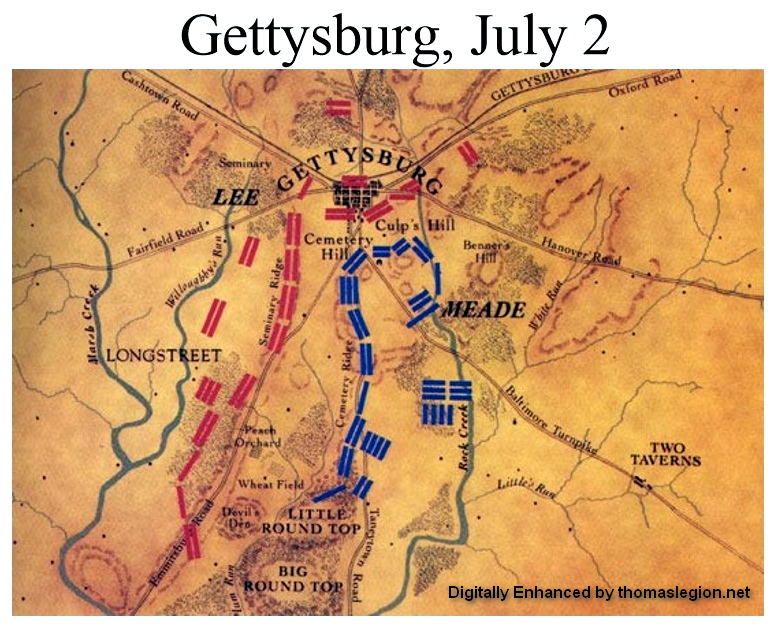

Early on the morning of July 2nd, Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was positioned on Seminary Ridge and extended northward, through Gettysburg

and then east on the Hanover Road. Meade's Army of the Potomac occupied Culp's and Cemetery Hills, with his line extended southward on Cemetery Ridge toward

Little Round Top. The U-shaped lines of both armies matched each other. General Lee still held

an advantage in numbers that morning and decided to move his troops into positions to strike at Meade from both flanks.

General James Longstreet's Corps was ordered southward toward the southern tip of the Confederate line to attack

the Union left flank near the Round Tops. Once Longstreet's troops were engaged, General Ewell would send his Confederates

against Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill on the Union right flank. General A.P. Hill's Corps

was positioned between the two other corps and remained on Seminary Ridge at this location. Hill's men were ordered to lay

in reserve until they were needed to support the attack, though heavy skirmishing with Union troops took place in the fields

west of the ridge throughout the day. Darkness called a halt to the Confederate assault before the last of Hill's troops could

be called into battle.

(About) Photo of Cemetery Ridge from Seminary Ridge at the McMillan Farm.

Little & Big Round Top are to the right. Gettysburg NMP.

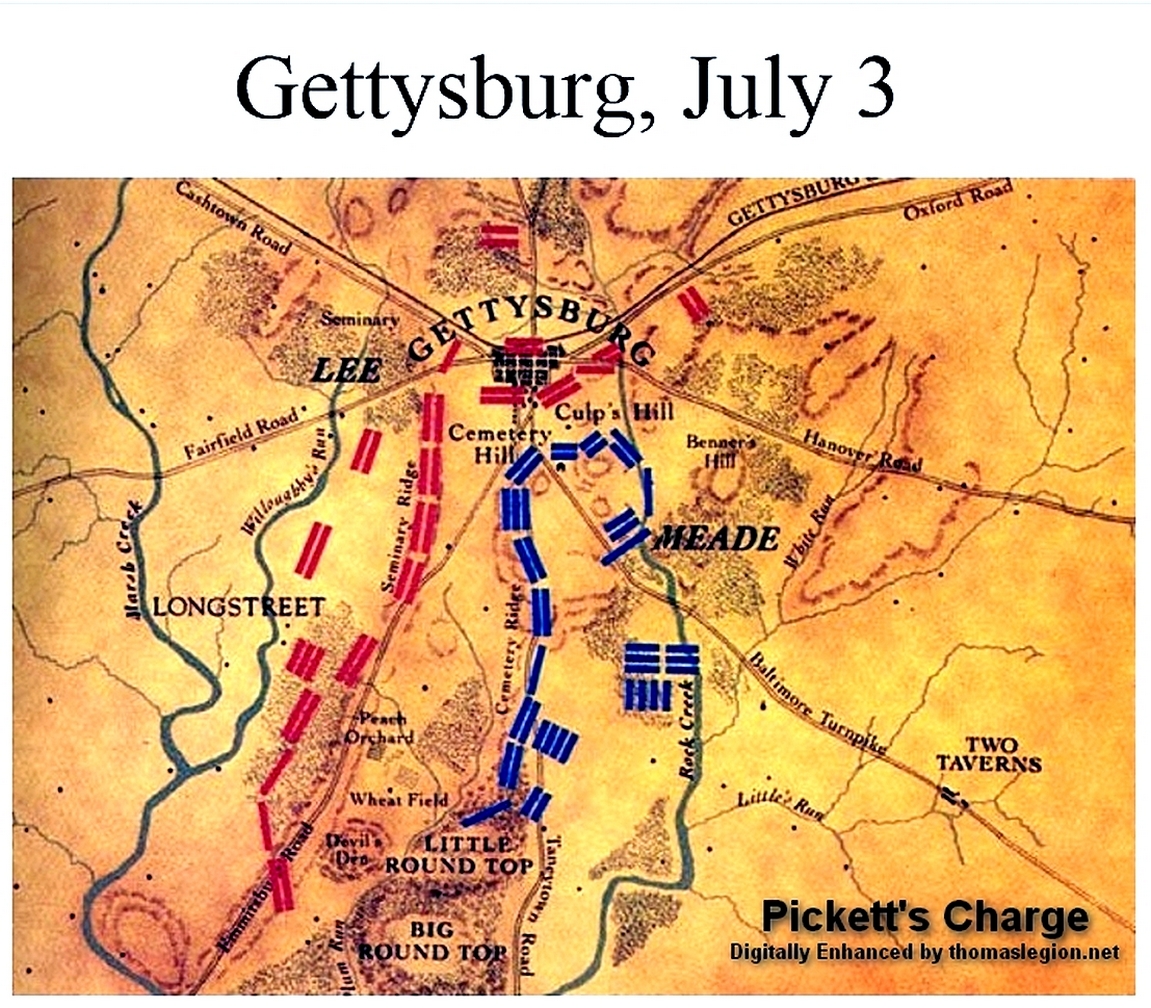

It was from this location at Cemetery Ridge on July 3, that Confederates

commanded by Generals Pettigrew and Trimble stepped off to participate in the attack on the Union center. Though this attack

is called "Pickett's Charge", it was not just Virginia troops under General Pickett who made the assault-

regiments from North Carolina, Alabama, Tennessee, and Mississippi made up the column that marched from this area. The long

treeless slope ahead of the Confederates offered no cover from the withering Union cannon fire on Cemetery Hill and Cemetery

Ridge. When the left brigade of Pettigrew's line began to crumble and retreat, General Trimble pushed his two brigades to the

left to fill the gap. The men marched on to the Emmitsburg Road and assaulted the Union line north of the Angle. Like Pickett's

men, they too were thrown back after considerable loss. Seminary Ridge

today is marked by West Confederate Avenue, a park road designed and constructed at the turn of the century. It is lined with

markers to Confederate brigades and artillery batteries accompanied by almost 80 artillery pieces, including many original

guns of Confederate manufacture, that mark the general locations of Confederate units during the battle. The majority of monuments

erected by Southern states are located on West Confederate Avenue, most notably the North Carolina and Tennessee monuments,

Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Arkansas monuments, and the Virginia Monument, which has the equestrian

statue of General Lee.

History

The battle began early on the morning of July 1 when a Confederate column under General Henry Heth, marching

east from Cashtown encountered Union pickets three miles west of Gettysburg. Opponents sparred over the gently rolling farmland

west of Gettysburg, until the cavalrymen were forced back to McPherson's Ridge where Union infantry were just then arriving

at 10 a.m.

On the morning of July 1, Union cavalry in the division of Brig. Gen. John Buford were awaiting the approach

of Confederate infantry forces from the direction of Cashtown, to the northwest. Confederate forces from the brigade of Brig.

Gen. J. Johnston Pettigrew had briefly clashed with Union forces the day before but believed they were Pennsylvania militia

of little consequence, not the regular army cavalry that was screening the approach of the Army of the Potomac.

General Buford realized the importance of the high ground directly to the south of Gettysburg. He knew that

if the Confederates could gain control of the heights, Meade's army would have a hard time dislodging them. He decided to

utilize three ridges west of Gettysburg: Herr Ridge, McPherson Ridge, and Seminary Ridge (proceeding west to east toward the

town). These were appropriate terrain for a delaying action by his small division against superior Confederate infantry forces,

meant to buy time awaiting the arrival of Union infantrymen who could occupy the strong defensive positions south of town,

Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge, and Culp's Hill. Early that morning, Reynolds, who was commanding the Left Wing of the Army

of the Potomac, ordered his corps to march to Buford's location, with the XI Corps (Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard) to follow

closely behind.

| Battle of Seminary Ridge |

|

| Action at Seminary Ridge |

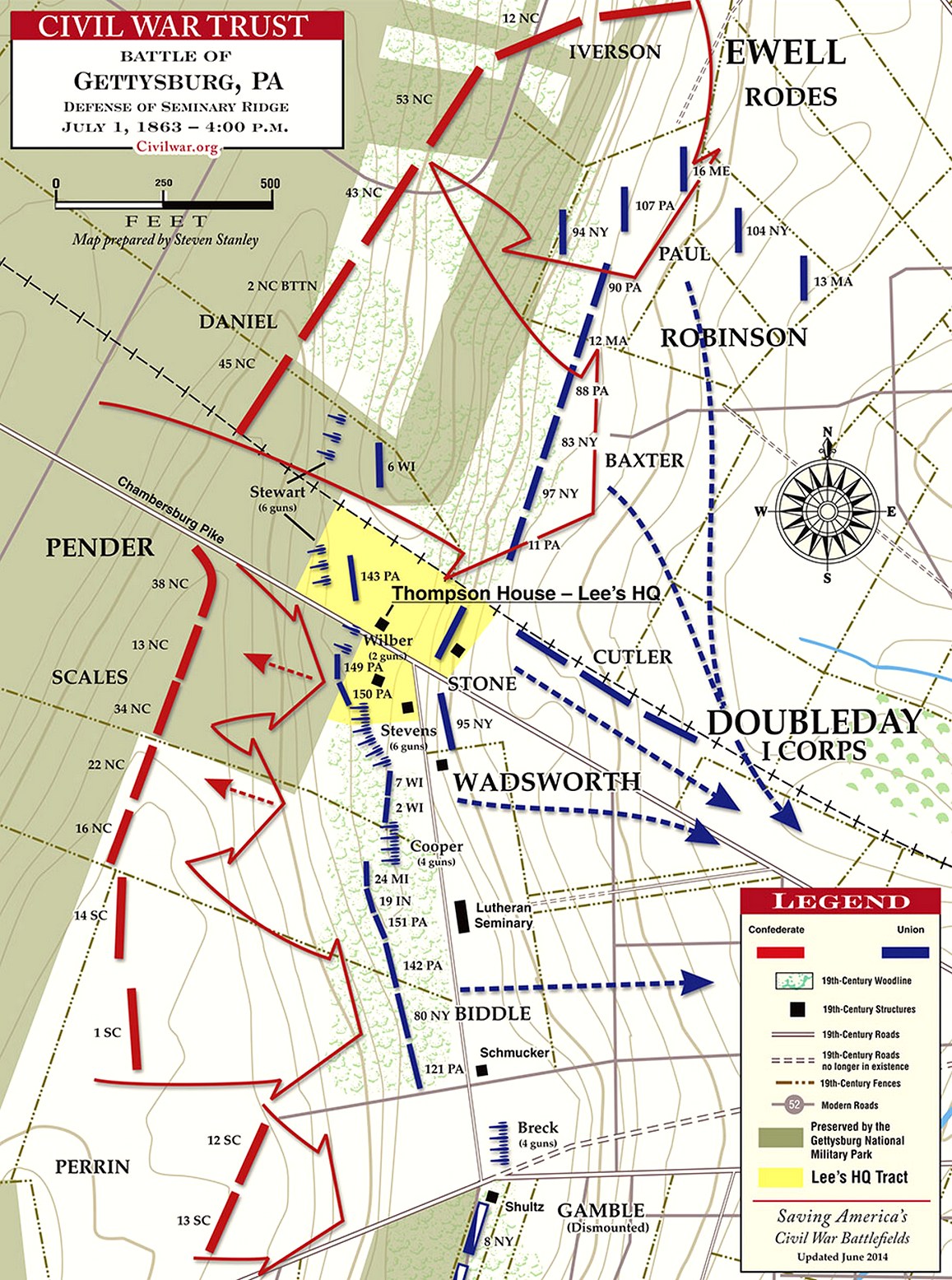

(About) On the morning of July 1, a Union cavalry division under Brig.

Gen. John Buford was awaiting the approach of Confederate infantry from the direction of Cashtown, to the northwest. Buford

realized the importance of the high ground directly to the south of Gettysburg and knew that if the Confederates could gain

control of the heights, Meade's army would have a hard time dislodging them. Buford decided to utilize three ridges west

of Gettysburg: Herr Ridge, McPherson Ridge, and Seminary Ridge (proceeding west to east toward the town). It was appropriate

ground for a delaying action by his small division against superior Confederate infantry forces.

Confederate Maj. Gen. Henry Heth's division, from Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill's Third

Corps, advanced towards Gettysburg. Heth deployed no cavalry and led, unconventionally, with the artillery battalion of Major

William J. Pegram. Two infantry brigades followed, commanded by Brig. Gens. James J. Archer and Joseph R. Davis, proceeding

easterly in columns along the Chambersburg Pike. Three miles west of town, about 7:30 a.m., Heth's two brigades met light

resistance from cavalry vedettes and deployed into line. Eventually, they reached dismounted troopers from Col. William Gamble's

cavalry brigade. The first shot of the battle was claimed to be fired by Lieutenant Marcellus E. Jones of the 8th Illinois

Cavalry, fired at an unidentified man on a gray horse over a half-mile away; the act was merely symbolic. Buford's 2,748 troopers

would soon be faced with 7,600 Confederate infantrymen, deploying from columns into line of battle.

Gamble's men mounted determined resistance and delaying tactics from behind

fence posts with rapid fire from their breech-loading carbines. It is a modern myth that they were armed with multi-shot repeating

carbines. Nevertheless, they were able to fire two or three times faster than a muzzle-loaded carbine or rifle. Also, the

breech-loading design meant that Union troops did not have to stand to reload and could do so safely behind cover. This was

a great advantage over the Confederates, who still had to stand to reload, thus providing an easier target. But this was so

far a relatively bloodless affair. By 10:20 a.m., the Confederates had reached Herr Ridge and had pushed the Federal cavalrymen

east to McPherson Ridge, when the vanguard of the I Corps finally arrived, the division of Maj. Gen. James S. Wadsworth. The

troops were led personally by Gen. Reynolds, who conferred briefly with Buford and hurried back to bring more men forward.

| First Day, Battle of Gettysburg |

|

| Battle of Gettysburg, July 1, 1863 |

(Right) Once the Confederates secured Seminary Ridge on the 1st, it would

be used as a staging area for assaults on Union positions on the second and third days of the fight at Gettysburg.

The morning infantry fighting occurred on either side of the Chambersburg

Pike, mostly on McPherson Ridge. To the north, an unfinished railroad bed opened three shallow cuts in the ridges. To the

south, the dominant features were Willoughby Run and Herbst Woods (sometimes called McPherson Woods, but they were the property

of John Herbst). Brig. Gen. Lysander Cutler's Union brigade opposed Davis's brigade; three of Cutler's regiments were north

of the Pike, two to the south. To the left of Cutler, Brig. Gen. Solomon Meredith's Iron Brigade opposed Archer.

| Battle of Gettysburg, July 1, 1863 |

|

| Battle of Gettysburg, July 1, 1863 |

General Reynolds directed both brigades into position and placed guns from

the Maine battery of Capt. James A. Hall where Calef's had stood earlier. While the general rode his horse along the east

end of Herbst Woods, shouting "Forward men! Forward for God's sake, and drive those fellows out of the woods," he fell from

his horse, killed instantly by a bullet striking him behind the ear. (Some historians believe Reynolds was felled by a sharpshooter,

but it is more likely that he was killed by random shot in a volley of rifle fire directed at the 2nd Wisconsin.) Maj. Gen.

Abner Doubleday assumed command of the I Corps.

On the right of the Union line, three regiments of Cutler's brigade were

fired on by Davis's brigade before they could get into position on the ridge. Davis's line overlapped the right of Cutler's,

making the Union position untenable, and Wadsworth ordered Cutler's regiments back to Seminary Ridge. The commander of the

147th New York, Lt. Col. Francis C. Miller, was shot before he could inform his troops of the withdrawal, and they remained

to fight under heavy pressure until a second order came. In under 30 minutes, 45% of Gen. Cutler's 1,007 men became casualties,

with the 147th losing 207 of its 380 officers and men. Some of Davis's

victorious men turned toward the Union positions south of the railroad bed while others drove east toward Seminary Ridge.

This defocused the Confederate effort north of the pike.

In the afternoon, there was fighting both west (Hill's Corps renewing

their attacks on the I Corps) and north (Ewell's Corps attacking the I and XI Corps) of Gettysburg. Ewell, on Oak Hill with

Rodes, saw Howard's troops deploying before him, and he interpreted this as the start of an attack and implicit permission

to set aside Gen. Lee's order not to bring about a general engagement.

Rodes initially sent three brigades south against Union troops that represented the right flank of the I

Corps and the left flank of the XI Corps: from east to west, Brig. Gen. George P. Doles, Col. Edward A. O'Neal, and Brig.

Gen. Alfred Iverson. Doles's Georgia brigade stood guarding the flank, awaiting the arrival of Early's division. Both O'Neal's

and Iverson's attacks fared poorly against the six veteran regiments in the brigade of Brig. Gen. Henry Baxter, manning a

line in a shallow inverted V, facing north on the ridge behind the Mummasburg Road. O'Neal's men were sent forward without

coordinating with Iverson on their flank and fell back under heavy fire from the I Corps troops.

Iverson failed to perform even a rudimentary reconnaissance and sent his

men forward blindly while he stayed in the rear (as had O'Neal, minutes earlier). More of Baxter's men were concealed in woods

behind a stone wall and rose to fire withering volleys from less than 100 yards away, creating over 800 casualties among the

1,350 North Carolinians. Stories are told about groups of dead bodies lying in almost parade-ground formations, heels of their

boots perfectly aligned. (The bodies were later buried on the scene, and this area is today known as "Iverson's Pits", source

of many local tales of supernatural phenomena.)

| Seminary Ridge, Battle of Gettysburg |

|

| Seminary Ridge and Gettysburg |

Baxter's brigade was worn down and out of ammunition. At 3:00 p.m. he withdrew

his brigade, and Gen. Robinson replaced it with the brigade of Brig. Gen. Gabriel R. Paul. Rodes then committed his two reserve

brigades: Brig. Gens. Junius Daniel and Dodson Ramseur. Ramseur attacked first, but Paul's brigade held its crucial position.

Paul had a bullet go in one temple and out the other, blinding him permanently (he survived the wound and lived 20 more years

after the battle). Before the end of the day, three other commanders of that brigade were wounded.

Daniel's North Carolina brigade then attempted to break the I Corps line

to the southwest along the Chambersburg Pike. They ran into stiff resistance from Col. Roy Stone's Pennsylvania "Bucktail

Brigade" in the same area around the railroad cut as the morning's battle. Fierce fighting eventually ground to a standstill.

Rodes's original faulty attack at 2:00 had stalled, but he launched

his reserve brigade, under Ramseur, against Paul's Brigade in the salient on the Mummasburg Road, with Doles's Brigade against

the left flank of the XI Corps. Daniel's Brigade resumed its attack, now to the east against Baxter on Oak Ridge. This time

Rodes was more successful, mostly because Early coordinated an attack on his flank. In the west, the Union troops had fallen

back to the Seminary and built hasty breastworks running 600 yards north-south before the western face of Schmucker Hall,

bolstered by 20 guns of Wainwright's battalion. Dorsey Pender's division of Hill's Corps stepped through the exhausted lines

of Heth's men at about 4:00 p.m. to finish off the I Corps survivors. The brigade of Brig. Gen. Alfred M. Scales attacked

first, on the northern flank. His five regiments of 1,400 North Carolinians were virtually annihilated in one of the fiercest

artillery barrages of the war, rivaling Pickett's Charge to come, but on a more concentrated scale. Twenty guns spaced only

5 yards apart fired spherical case, explosive shells, canister, and double canister rounds into the approaching brigade, which

emerged from the fight with only 500 men standing and a single lieutenant in command. Scales wrote afterwards that he found

"only a squad here and there marked the place where regiments had rested."

| Second Day, Battle of Gettysburg |

|

| Battle of Gettysburg, July 2, 1863 |

The attack continued in the southern-central area, where Col.

Abner M. Perrin ordered his South Carolina brigade (four regiments of 1,500 men) to advance rapidly without pausing to fire.

Perrin was prominently on horseback leading his men but miraculously was untouched. He directed his men to a weak point in

the breastworks on the Union left, a 50-yard gap between Biddle's left-hand regiment, the 121st Pennsylvania, and Gamble's

cavalrymen, attempting to guard the flank. They broke through, enveloping the Union line and rolling it up to the north as

Scales's men continued to pin down the right flank. By 4:30 p.m., the Union position was untenable, and the men could see

the XI Corps retreating from the northern battle, pursued by masses of Confederates. Doubleday ordered a withdrawal east to

Cemetery Hill.

On the southern flank, the North Carolina brigade of Brig. Gen. James H.

Lane contributed little to the assault; he was kept busy by a clash with Union cavalry on the Hagerstown Road. Brig. Gen.

Edward L. Thomas's Georgia Brigade was in reserve well to the rear, not summoned by Pender or Hill to assist or exploit the

breakthrough.

The sequence of retreating units remains unclear. Each of the two corps

cast blame on the other. There are three main versions of events extant. The first, most prevalent, version is that the fiasco

on Barlow's Knoll triggered a collapse that ran counterclockwise around the line. The second is that both Barlow's line and

the Seminary defense collapsed at about the same time. The third is that Robinson's division in the center gave way and that

spread both left and right. Gen. Howard told Gen. Meade that his corps was forced to retreat only because the I Corps collapsed

first on his flank, which may have reduced his embarrassment but was unappreciated by Doubleday and his men. (Doubleday's

career was effectively ruined by Howard's story.)

Union troops retreated in different states of order. The brigades on Seminary

Ridge were said to move deliberately and slowly, keeping in control, although Col. Wainwright's artillery was not informed

of the order to retreat and found themselves alone. When Wainwright realized his situation, he ordered his gun crews to withdraw

at a walk, not wishing to panic the infantry and start a rout. As pressure eventually increased, Wainwright ordered his 17

remaining guns to gallop down Chambersburg Street, three abreast. A.P. Hill failed to commit any of his reserves to the pursuit

of the Seminary defenders, a great missed opportunity.

Near the railroad cut, Daniel's Brigade renewed their assault, and almost

500 Union soldiers surrendered and were taken prisoner. Paul's Brigade, under attack by Ramseur, became seriously isolated

and Gen. Robinson ordered it to withdraw. He ordered the 16th Maine to hold its position "at any cost" as a rear guard against

the enemy pursuit. The regiment, commanded by Col. Charles Tilden, returned to the stone wall on the Mummasburg Road, and

their fierce fire gave sufficient time for the rest of the brigade to escape, which they did, in considerably more disarray

than those from the Seminary. The 16th Maine started the day with 298 men, but at the end of this holding action there were

only 35 survivors.

For the XI Corps, it was a sad reminder of their retreat at Chancellorsville

in May. Under heavy pursuit by Hays and Avery, they clogged the streets of the town; no one in the corps had planned routes

for this contingency. Hand-to-hand fighting broke out in various places. Parts of the corps conducted an organized fighting

retreat, such as Coster's stand in the brickyard. The private citizens of Gettysburg panicked amidst the turmoil, and artillery

shells bursting overhead and fleeing refugees added to the congestion. Some soldiers sought to avoid capture by hiding in

basements and in fenced backyards. Gen. Alexander Schimmelfennig was one such person who climbed a fence and hid behind a

woodpile in the kitchen garden of the Garlach family for the rest of the three-day battle. The only advantage that the XI

Corps soldiers had was that they were familiar with the route to Cemetery Hill, having passed through that way in the morning;

many in the I Corps, including senior officers, did not know where the cemetery was located.

| Third Day, Battle of Gettysburg |

|

| Battle of Gettysburg, July 3, 1863 |

As the Union troops climbed Cemetery Hill, they encountered the determined

Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock. At midday, Gen. Meade was nine miles south of Gettysburg in Taneytown, Maryland, when he

heard that Reynolds had been killed. He immediately dispatched Hancock, commander of the II Corps and his most trusted subordinate,

to the scene with orders to take command of the field and to determine whether Gettysburg was an appropriate place for a major

battle. (Meade's original plan had been to man a defensive line on Pipe Creek, a few miles south in Maryland. But the serious

battle underway was making that a difficult option.)

When Hancock arrived on Cemetery Hill, he met with Howard and they had a

brief disagreement about Meade's command order. As the senior officer, Howard yielded only grudgingly to Hancock's direction.

Although Hancock arrived after 4:00 p.m. and commanded no units on the field that day, he took control of the Union troops

arriving on the hill and directed them to defensive positions with his "imperious and defiant" (and profane) persona. As to

the choice of Gettysburg as the battlefield, Hancock told Howard "I think this the strongest position by nature upon which

to fight a battle that I ever saw." When Howard agreed, Hancock concluded the discussion: "Very well, sir, I select this as

the battle-field." Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, chief engineer of the Army of the Potomac, inspected the ground and concurred

with Hancock.

The first day at Gettysburg—more significant than simply a prelude to the bloody second and third

days—ranks as the 23rd biggest battle of the war by number of troops engaged. About one quarter of Meade's army (22,000

men) and one third of Lee's army (27,000) were engaged. Union casualties were almost 9,000, Confederate slightly more than

6,000.

Commander of a Division for One Charge

|

| (Generals in Gray) |

Major General Isaac R. Trimble accompanied the Army of Northern Virginia northward to Gettysburg

without troops to command though he was an experienced officer having previously served under "Stonewall" Jackson in the Shenandoah

Valley and at Second Manassas where he had been wounded. Reorganization of the army after Chancellorsville left the general

without troops to command, so he rode with the army attached to General Ewell's headquarters, a role he was evidently dissatisfied

with and expressed his displeasure to General Lee. As fate would have it, the injury to General William Dorsey Pender on July

2nd left a vacancy that Trimble could fill and he was assigned to command Pender's Division in the great attack on the Union

center known as "Pickett's Charge." Unfortunately, Trimble's tenure in command was short. He was seriously wounded near the

Emmitsburg Road during the charge when a musket ball slammed into his leg, shattering the bone. He relinquished command with

the remark: "If the troops (I) had the honor to command today for the first time cannot take that position, all hell can not

take it!" That night, the general's leg was amputated in a Confederate field hospital. Captured when the Confederate army

retreated, the general convalesced in a Federal hospital for prisoners in Philadelphia. Trimble was exchanged in 1865 but

his career as a field officer was finished. After the close of the war, he returned to the city of Baltimore where he had

previously been employed as general superintendent of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad, and lived a quiet life as a consulting

engineer until his death in 1888.

North Carolina's Sacrifice at Gettysburg

| NC Monument at Gettysburg |

|

| North Carolina Monument |

The North Carolina Monument is dedicated to its forty-two regiments and

batteries which served at Gettysburg. The North Carolina legislature appointed a special commission of veterans to visit the

battlefield park in 1913 and return with a design proposal for a state monument to be place there, but the advent of World

War I put the state's plans on hold. It was not until 1927 when the plan was rekindled by the North Carolina Chapter of the

United Daughters of the Confederacy and Governor Angus McLean. The state appropriated $50,000 to purchase the site, contract

with an artist for the design and manufacture, and provide landscape features as an appropriate setting.

(Right) North Carolina Monument. Gettysburg NMP.

Dedicated on July 3, 1929, the North Carolina Monument is the work of world

re-known sculptor Gutzon Borglum (1867-1941) whose most famous work is the four presidents on Mount Rushmore. The monument

represents a group of North Carolina soldiers in "Pickett's Charge". Fifteen North Carolina infantry regiments, all of which had suffered heavily

during the first day's battle, participated in the attack. The monument is accompanied by dogwoods, which is the state tree,

and a stone monolith that lists the North Carolina commands present at Gettysburg.

The state's sacrifice at the Battle of Gettysburg was humbling; one in every

four Confederate soldiers who fell here was from the "Old North State".

Analysis

Cemetery Ridge was unoccupied for much of the first day until the Union army

retreated from its positions north of town, when the divisions of Brig. Gen. John C. Robinson and Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday

from the I Corps were placed on the northern end of the ridge, protecting the left flank of the XI Corps on Cemetery Hill.

After the XII Corps arrived, Maj. Gen. John W. Geary's Second Division was sent to the southern end of the ridge near Little

Round Top; Brig. Gen. John Buford's cavalry division formed a skirmish line in the fields between Cemetery Ridge and Seminary

Ridge. The III Corps arrived about 8 p.m. and replaced Geary's division (which was sent to Culp's Hill); the II Corps arrived

about 10:30 p.m. and camped immediately behind the III Corps.

During the morning of the battle's 2nd day (July 2), Army of the Potomac commander

Maj. Gen. George G. Meade shifted units to receive an expected Confederate attack on his positions. The II Corps was placed

in the center of Cemetery Ridge, with Brig. Gen. Alexander Hays's division on the corps' right, John Gibbon's division in

the center around the Angle, and John C. Caldwell's division on the left, adjacent to the III Corps; Robinson's division of

the I Corps was placed in reserve behind the XI Corps. The V Corps was formed in reserve behind the II Corps. In the late

afternoon, the end of the Confederate Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws's assault drove portions of Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles's III

Corps line back to the southern end of Cemetery Ridge, and Brig. Gen. Ambrose Wright's Confederate brigade temporarily captured

the southern end of the Angle before being driven back to Seminary Ridge by the Philadelphia Brigade.

The Confederate artillery bombardment preceding Pickett's Charge on July 3

battered Cemetery Ridge, and Union artillery on the ridge counterfired to Seminary Ridge. Thirty-four Union cannons were disabled,

but the three Confederate divisions of the subsequent infantry assault (Pickett's of the First Corps and Pettigrew's and Trimble's

of the Third Corps), attacked the Union II Corps at the "stone fence" at the Angle. Heavy rifle and artillery fire prevented

all but about 250 Confederates led by Lewis Armistead from penetrating the Union line to the high water mark of the Confederacy.

Armistead was mortally wounded. Two brigades of Anderson's Division, assigned to protect Pickett's right flank during the

charge, reached a more southern portion of the Union line at Cemetery Ridge soon after the repulse of Pickett's Division,

but were driven back with 40% casualties by the 2nd Vermont Brigade.

Lee then led his battered army on a torturous retreat back to Virginia, where

he would remain for the duration of the war. While as many as 51,000 soldiers from both armies were killed, wounded,

captured or missing in the three-day battle, its strategy and tactics are still being studied from casual students to elite

schools such as West Point.

Sources: National Park Service; Gettysburg National Military Park; Civil

War Trust; National Archives; Library of Congress; Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies.

Recommended Reading: Gettysburg--The First Day,

by Harry W. Pfanz (Civil War America)

(Hardcover). Description: Though a great deal has been

written about the battle of Gettysburg, much of it has focused

on the events of the second and third days. With this book, the first day's fighting finally receives its due. Harry Pfanz,

a former historian at Gettysburg National

Military Park and author of

two previous books on the battle, presents a deeply researched, definitive account of the events of July 1, 1863. Continued below…

After sketching the background of the

Gettysburg

campaign and recounting the events immediately preceding the battle, Pfanz offers a detailed tactical description of the first

day's fighting. He describes the engagements in McPherson Woods, at the Railroad Cuts, on Oak

Ridge, on Seminary Ridge, and at Blocher's Knoll, as well as the retreat of Union forces through Gettysburg and the Federal rally on Cemetery Hill. Throughout, he draws on

deep research in published and archival sources to challenge some of the common assumptions about the battle--for example,

that Richard Ewell's failure to press an attack against Union troops at Cemetery Hill late on the first day ultimately cost

the Confederacy the battle.

Recommended Reading: Gettysburg--The Second Day, by Harry W. Pfanz (624 pages). Description: The second day's fighting at Gettysburg—the

assault of the Army of Northern Virginia against the Army of the Potomac on 2 July 1863—was

probably the critical engagement of that decisive battle and, therefore, among the most significant actions of the Civil War.

Harry Pfanz, a former historian at Gettysburg National Military Park,

has written a definitive account of the second day's brutal combat. He begins by introducing the men and units that were to

do battle, analyzing the strategic intentions of Lee and Meade as commanders of the opposing armies, and describing the concentration

of forces in the area around Gettysburg. He then examines

the development of tactical plans and the deployment of troops for the approaching battle. But the emphasis is on the fighting

itself. Pfanz provides a thorough account of the Confederates' smashing assaults—at Devil's Den and Little Round Top,

through the Wheatfield and the Peach Orchard, and against the Union center at Cemetery Ridge. He also details the Union defense

that eventually succeeded in beating back these assaults, depriving Lee's gallant army of victory. Continued below.

Pfanz analyzes

decisions and events that have sparked debate for more than a century. In particular he discusses factors underlying the Meade-Sickles

controversy and the questions about Longstreet's delay in attacking the Union left. The narrative is also enhanced by thirteen superb maps, more than eighty illustrations,

brief portraits of the leading commanders, and observations on artillery, weapons, and tactics that will be of help even to

knowledgeable readers. Gettysburg—The Second Day

is certain to become a Civil War classic. What makes the work so authoritative is Pfanz's mastery of the Gettysburg literature and his unparalleled knowledge of the ground on which the fighting

occurred. His sources include the Official Records, regimental histories and personal reminiscences from soldiers North and

South, personal papers and diaries, newspaper files, and last—but assuredly not least—the Gettysburg battlefield.

Pfanz's career in the National Park Service included a ten-year assignment as a park historian at Gettysburg. Without doubt, he knows the terrain of the battle as well as he knows the battle

itself.

Recommended Reading: Gettysburg--Culp's

Hill and Cemetery Hill (Civil War America)

(Hardcover). Description: In this companion to his celebrated earlier book, Gettysburg—The

Second Day, Harry Pfanz provides the first definitive account of the fighting between the Army of the Potomac and Robert E.

Lee's Army of Northern Virginia at Cemetery Hill and Culp's Hill—two of the most critical engagements fought at Gettysburg on 2 and 3 July 1863. Pfanz provides detailed tactical accounts

of each stage of the contest and explores the interactions between—and decisions made by—generals on both sides.

In particular, he illuminates Confederate lieutenant general Richard S. Ewell's controversial decision not to attack Cemetery

Hill after the initial southern victory on 1 July. Continued below.

Pfanz also explores other

salient features of the fighting, including the Confederate occupation of the town of Gettysburg,

the skirmishing in the south end of town and in front of the hills, the use of breastworks on Culp's Hill, and the small but

decisive fight between Union cavalry and the Stonewall Brigade. About the Author: Harry W. Pfanz is author of Gettysburg--The First

Day and Gettysburg--The Second Day. A lieutenant, field artillery,

during World War II, he served for ten years as a historian at Gettysburg National Military Park and retired from the position

of Chief Historian of the National Park Service in 1981. To purchase additional books from Pfanz, a convenient Amazon

Search Box is provided at the bottom of this page.

Recommended Reading: Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage. Description: America's Civil War raged for more than four years, but it is the three days of fighting in the Pennsylvania countryside in July 1863 that continues to fascinate, appall, and inspire new

generations with its unparalleled saga of sacrifice and courage. From Chancellorsville, where General Robert E. Lee launched

his high-risk campaign into the North, to the Confederates' last daring and ultimately-doomed act, forever known as Pickett's

Charge, the battle of Gettysburg gave the Union army a victory that turned back the boldest and perhaps greatest chance for

a Southern nation. Continued below...

Now, acclaimed

historian Noah Andre Trudeau brings the most up-to-date research available to a brilliant, sweeping, and comprehensive history

of the battle of Gettysburg that sheds fresh light on virtually every aspect of it. Deftly balancing his own

narrative style with revealing firsthand accounts, Trudeau brings this engrossing human tale to life as never before.

Recommended Reading: Pickett's Charge,

by George Stewart. Description: The author

has written an eminently readable, thoroughly enjoyable, and well-researched book on the third day of the Gettysburg battle, July 3, 1863. An especially rewarding read if one has toured, or plans

to visit, the battlefield site. The author's unpretentious, conversational style of writing succeeds in putting the reader

on the ground occupied by both the Confederate and Union forces before, during and after

Pickett's and Pettigrew's famous assault on Meade's Second Corps. Continued below...

Interspersed

with humor and down-to-earth observations concerning battlefield conditions, the author conscientiously describes all aspects

of the battle, from massing of the assault columns and pre-assault artillery barrage to the last shots and the flight of the

surviving rebels back to the safety of their lines… Having visited Gettysburg several years ago, this superb volume makes me

want to go again.

Recommended Reading: Pickett's Charge--The Last Attack at Gettysburg (Hardcover). Description: Pickett's Charge

is probably the best-known military engagement of the Civil War, widely regarded as the defining moment of the battle of Gettysburg and celebrated as the high-water mark of the Confederacy.

But as Earl Hess notes, the epic stature of Pickett's Charge has grown at the expense of reality, and the facts of the attack

have been obscured or distorted by the legend that surrounds them. With this book, Hess sweeps away the accumulated myths

about Pickett's Charge to provide the definitive history of the engagement. Continued below...

Drawing on

exhaustive research, especially in unpublished personal accounts, he creates a moving narrative of the attack from both Union and Confederate

perspectives, analyzing its planning, execution, aftermath, and legacy. He also examines the history of the units involved,

their state of readiness, how they maneuvered under fire, and what the men who marched in the ranks thought about their participation

in the assault. Ultimately, Hess explains, such an approach reveals Pickett's Charge both as a case study in how soldiers

deal with combat and as a dramatic example of heroism, failure, and fate on the battlefield.

Recommended Reading:

Pickett's Charge in History and Memory. Description: Pickett's Charge--the Confederates' desperate (and failed) attempt to break the Union

lines on the third and final day of the Battle of Gettysburg--is best remembered as the turning point of the U.S. Civil War.

But Penn State

historian Carol Reardon reveals how hard it is to remember the past accurately, especially when an event such as this one

so quickly slipped into myth. Continued

below...

She writes,

"From the time the battle smoke cleared, Pickett's Charge took on this chameleon-like aspect and, through a variety of carefully

constructed nuances, adjusted superbly to satisfy the changing needs of Northerners, Southerners, and, finally, the entire

nation." With care and detail, Reardon's

fascinating book teaches a lesson in the uses and misuses of history.

Recommended Reading: The Artillery of Gettysburg

(Hardcover). Description: The battle of Gettysburg

in July 1863, the apex of the Confederacy's final major invasion of the North, was a devastating defeat that also marked the

end of the South's offensive strategy against the North. From this battle until the end of the war, the Confederate armies

largely remained defensive. The Artillery of Gettysburg is a thought-provoking look at the role of the artillery during the

July 1-3, 1863 conflict. Continued below...

During the

Gettysburg

campaign, artillery had already gained the respect in both armies. Used defensively, it could break up attacking formations

and change the outcomes of battle. On the offense, it could soften up enemy positions prior to attack. And even if the results

were not immediately obvious, the psychological effects to strong artillery support could bolster the infantry and discourage

the enemy. Ultimately, infantry and artillery branches became codependent, for the artillery needed infantry support lest

it be decimated by enemy infantry or captured. The Confederate Army of Northern Virginia had modified its codependent command

system in February 1863. Prior to that, batteries were allocated to brigades, but now they were assigned to each infantry

division, thus decentralizing its command structure and making it more difficult for Gen. Robert E. Lee and his artillery

chief, Brig. Gen. William Pendleton, to control their deployment on the battlefield. The Union Army of the Potomac

had superior artillery capabilities in numerous ways. At Gettysburg,

the Federal artillery had 372 cannons and the Confederates 283. To make matters worse, the Confederate artillery frequently

was hindered by the quality of the fuses, which caused the shells to explode too early, too late, or not at all. When combined

with a command structure that gave Union Brig. Gen. Henry Hunt more direct control--than his Southern counterpart had over

his forces--the Federal army enjoyed a decided advantage in the countryside around Gettysburg. Bradley

M. Gottfried provides insight into how the two armies employed their artillery, how the different kinds of weapons functioned

in battle, and the strategies for using each of them. He shows how artillery affected the “ebb and flow” of battle

for both armies and thus provides a unique way of understanding the strategies of the Federal and Union

commanders.

Recommended

Reading: Into the Fight: Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg. Description: Challenging conventional views, stretching the minds of Civil War enthusiasts and scholars

as only John Michael Priest can, Into the Fight is both a scholarly and a revisionist interpretation of the most famous charge

in American history. Using a wide array of sources, ranging from the monuments on the Gettysburg

battlefield to the accounts of the participants themselves, Priest rewrites the conventional thinking about this unusually

emotional, yet serious, moment in our Civil War. Continued below...

Starting with

a fresh point of view, and with no axes to grind, Into the Fight challenges all interested in that stunning moment in history

to rethink their assumptions. Worthwhile for its use of soldiers’ accounts, valuable for its forcing the reader to rethink

the common assumptions about the charge, critics may disagree with this research, but they cannot ignore it.

Recommended Reading: Pickett's

Charge: Eyewitness Accounts At The Battle Of Gettysburg

(Stackpole Military History Series). Description: On

the final day of the battle of Gettysburg, Robert E. Lee ordered

one of the most famous infantry assaults of all time: Pickett's Charge. Following a thundering artillery barrage, thousands

of Confederates launched a daring frontal attack on the Union line. From their entrenched positions, Federal soldiers decimated

the charging Rebels, leaving the field littered with the fallen and several Southern divisions in tatters. Written by generals,

officers, and enlisted men on both sides, these firsthand accounts offer an up-close look at Civil War combat and a panoramic

view of the carnage of July 3, 1863.

|