|

|

Civil War Military

Army of Infantry, Cavalry, and Artillery

Civil War Military

Organization and Structure

The Union and Confederate Armies

| Civil War Army |

|

| Civil War muskets firing at night |

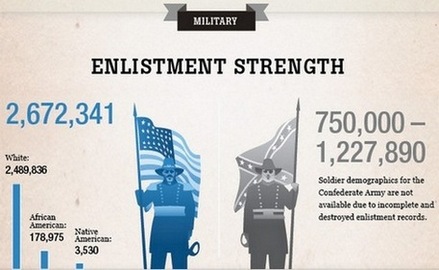

| Civil War Military and Total Soldiers |

|

| Union and Confederate Army of Infantry, Cavalry, and Artillery |

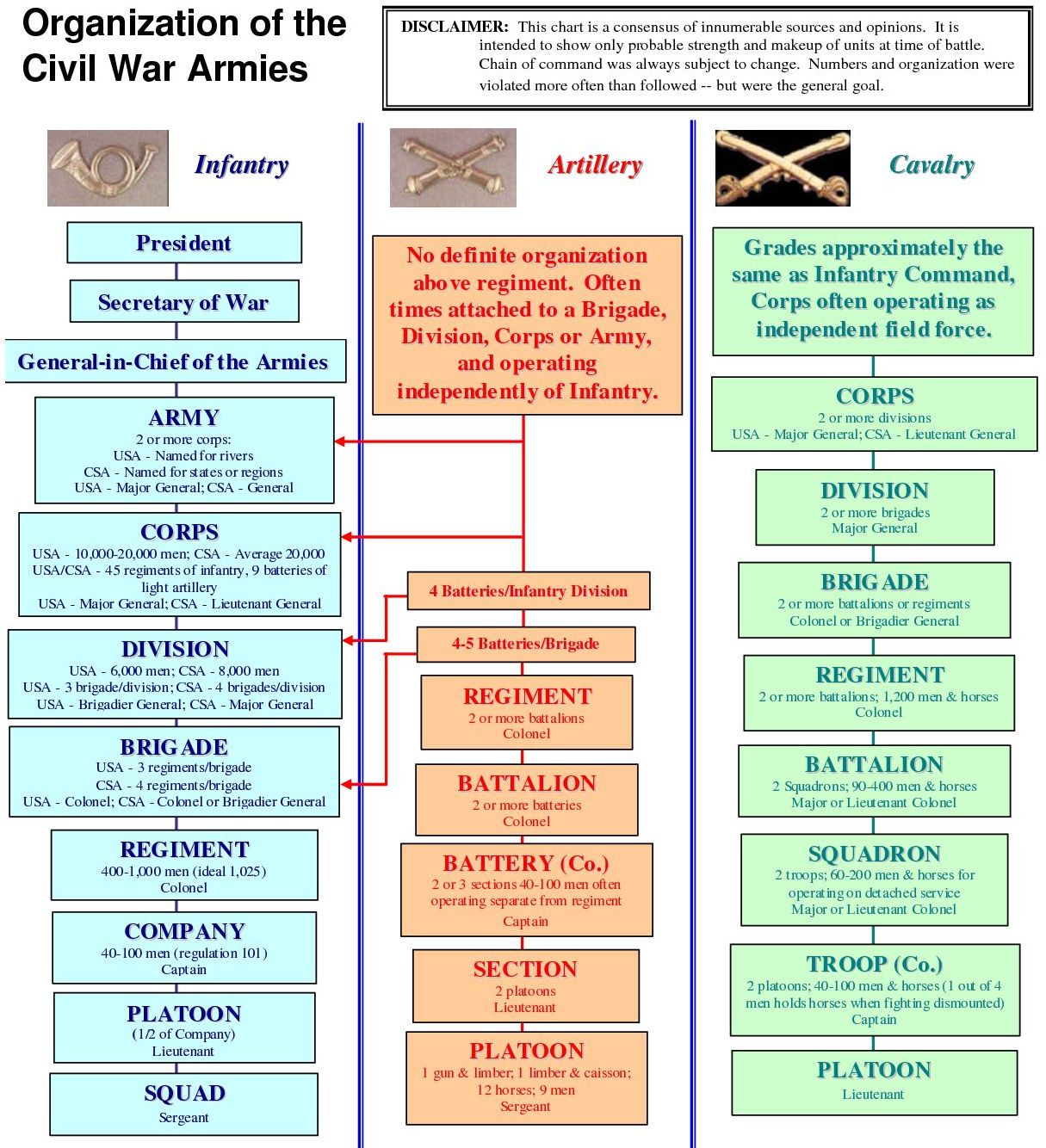

Structure of the Union and Confederate Armies

During the American Civil War (1861-1865), the army,

both Union and Confederate, consisted principally of artillery, infantry, and cavalry. Although organization and structure

for the opposing armies was nearly identical, the sizes of the units within the organization varied.

Because many of the Union and

Confederate officers were graduates of West Point, the opposing armies employed

similar organizations, tactics and strategies during the Civil War. Each side strived to maintain a well organized command

and control structure, with the goal of directing the army in the field of battle. The prolonged conflict, with its shifting

demands, however, forced both the Union and Confederate military to adapt and evolve to meet the necessary objectives.

Regiments were generally numbered and named for the state in which they were

organized and from which most of their soldiers hailed (for example, 1st Virginia Infantry Regiment). Confederate brigades

and divisions were generally named for their commanders, past or present (for example, the Stonewall Brigade), which often

created confusing circumstances. During Pickett's Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg (1863), Pickett's division was commanded

by George E. Pickett. But Heth's division, named for Henry Heth who was wounded on the first day of the battle, was commanded

by J. Johnston Pettigrew, and Pender's division by Isaac R. Trimble. Confederate general A. P. Hill's Light Division, meanwhile,

was actually the Army of Northern Virginia's largest division, with seven brigades.

The word "corps" was derived from the French term corps d'armee.

Union general George B. McClellan first created Union corps in March 1862—there would be forty-three altogether, each

designated by a number—and sometimes, as in the case of Ambrose E. Burnside's Ninth Corps, they moved from army to army

as necessary. In 1863, Union general Joseph Hooker, in a literal attempt to increase the Army of the Potomac's esprit de corps,

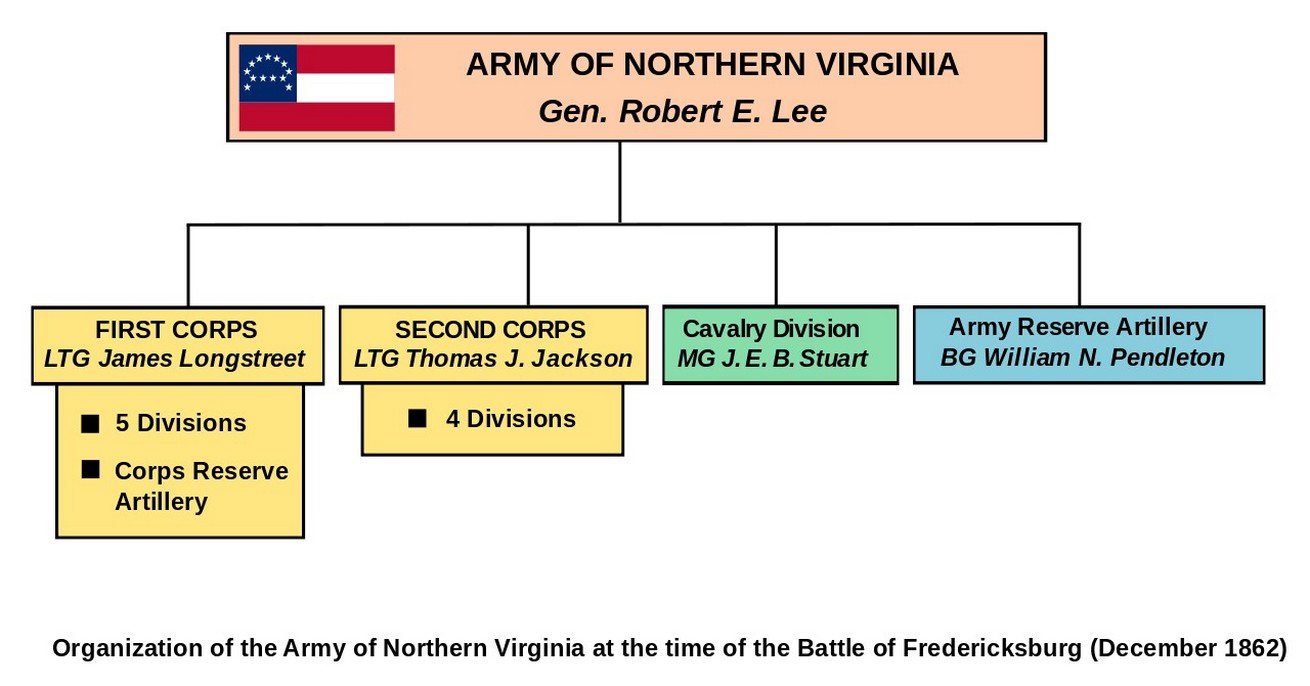

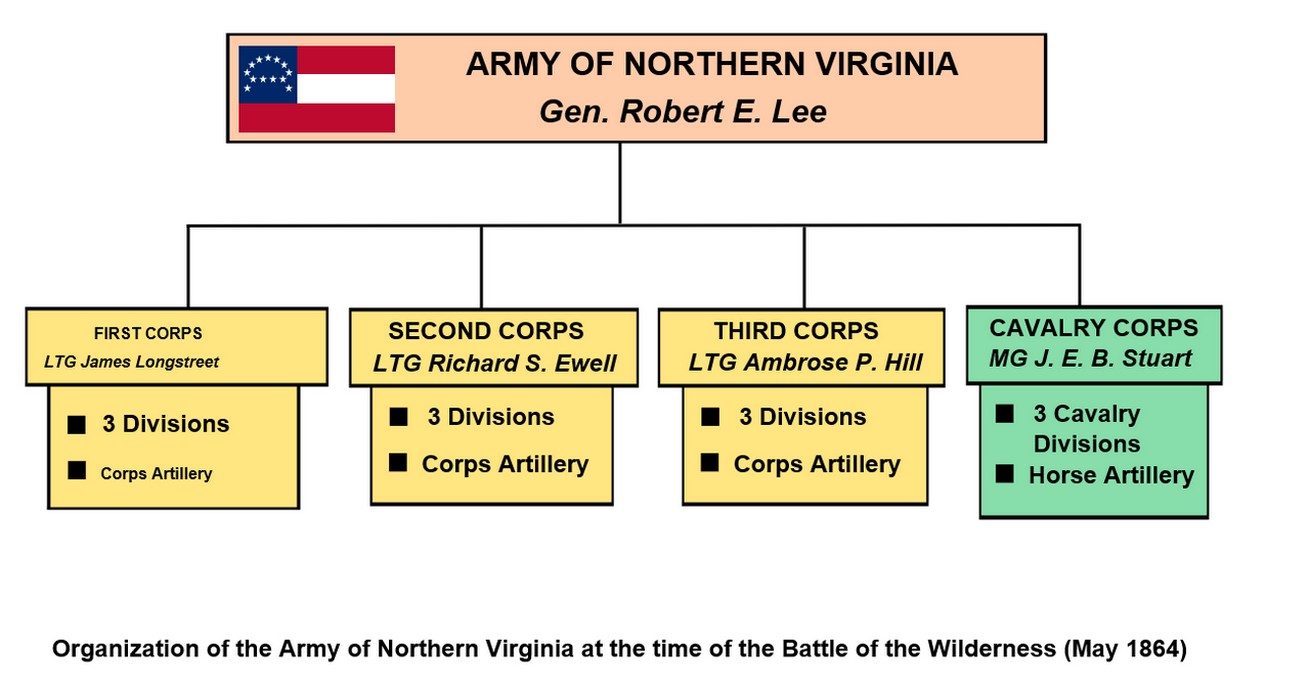

gave each Union corps its own special badge insignia. The Confederate Army of Northern Virginia was composed first of two,

then of three corps, known sometimes by their numbers, sometimes by their commanders' names. Confederate general James Longstreet

commanded the First Corps and Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson the Second Corps. After Jackson's death following the Battle of

Chancellorsville (1863), Robert E. Lee gave Jackson's Corps to Richard S. Ewell and created a new Third Corps, putting it

under the command of A. P. Hill. Richard H. Anderson briefly commanded a small Fourth Corps beginning in October 1864.

| Civil War Army: The Union and Confederate Military |

|

| Civil War Military Organization of Infantry, Cavalry, and Artillery |

| Military Field Guide for Civil War Army Formations |

|

| Civil War Military Battlefield Formations for Infantry, Cavalry, and Artillery |

Most Civil War soldiers were volunteers (or conscripts) and not members of

the Regular Army. Their regiments were temporary regiments of volunteers organized for the duration of the soldiers'

enlistment. Some officers, however, did hold Regular Army commissions (especially, but not exclusively, those who had

attended the United States Military Academy at West Point). As a result, a parallel system of rank developed in which a Union

officer might be, for instance, a major general of volunteers but only a colonel in the Regular Army.

Pay, meanwhile, was usually doled out according to the higher of the two ranks.

Because rank was sometimes awarded retroactively, there were sometimes pay disputes, as was the case with Winfield Scott,

who famously demanded twenty years of back pay when, before the war, Congress backdated his promotion to lieutenant general

to one of his famous Mexican War victories. The date of promotion was extremely important because both armies used seniority

to distinguish between two officers of the same rank. During the Battle of the Crater (1864), Union general-in-chief Ulysses

S. Grant was forced to issue separate orders to the head of the Army of the Potomac, George G. Meade, and Meade's practical

subordinate, the Ninth Corps commander Ambrose Burnside. Grant's problem was that because of seniority Burnside technically

outranked Meade and so resisted accepting orders from him.

Further confusing matters was a system of brevet ranks. Neither army awarded

medals; instead, they recognized valor through the issuance of temporary, honorary brevet ranks. The notoriously difficult

Scott was also involved in a row over brevet ranking, which led one antebellum observer of the military to declare, "The annals

of the army show more disputes to have arisen in consequence of this brevet rank than all other matters in dispute. It seems

to have had the property of transmuting the calmest and best-tempered men into hectoring and quarrelsome Bobadils." While

Scott only was promoted to brevet lieutenant general, Grant, during the Civil War, achieved the full-fledged Regular Army

rank of lieutenant general, the first officer to hold that rank since George Washington.

The highest Confederate rank was full general. During the summer of 1861,

Confederate president Jefferson Davis was authorized by Congress to appoint five men to the rank, in order of seniority—with

predictable results. Joseph E. Johnston, a hero of the First Battle of Manassas (1861) and the Regular Army's highest-ranking

officer to have resigned and joined the Confederacy, was only fourth on the list and accused the president of having "tarnished

my fair fame as a soldier and a man." The two feuded for the rest of the war.

Union and Confederate Army Organizations

ARMY

Armies were the largest of the "operational organizations." In the

case of the Federal forces, these generally took their name from their department. "The Federals followed a general policy

of naming their armies for the rivers near which they operated; the Confederates named theirs from the states or regions in

which they were active. Thus the Federals had an Army of the Tennessee -not to be confused with the Confederate Army of Tennessee."

Actually, it would appear that the armies took their names from the departments in which they operated (or were originally

formed), and these departments took their names from rivers in the case of the Federals and from states or regions in the

case of the Confederates. There were no firm rules on this matter of names, however: there was a Confederate Army of the Potomac;

and the Confederate Army of (the) Mississippi is referred to in the Official Records about as often with "the" as without.

These armies were at least 16 on the Union side and 23 on the Confederate

side.

| Civil War Army Organization and Order of Battle |

|

| Confederate Military Organization and Command and Control |

| Civil War Army Organization in Battle |

|

| Union and Confederate Army deployed Infantry, Artillery, and Cavalry as its Triune Fighting Force |

CORPS

Corps is derived from the French corps d'armee. Although corps

d'armee existed in the French army before Napoleon, he revamped them and popularized the phrase. A corps was composed

of 2 or more divisions and, except for Cavalry corps, included all arms of service. Corps

were established in the Union army in March 1862 by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan. A major general commanded each of

the 43 corps that were established in the Union army before the end of the war. Each corps was designated by a number,

I to XXV. Corps badges such as triangles, crescents, arrows, and acorns were adopted by most corps and worn by officers

and enlisted men. Of the Union corps 2 were noted for their failures: the XI Corps, which took flight after a surprise

attack by Lt. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's men at Chancellorsville and the IX Corps, which bungled the opportunity

of the Crater at Petersburg. More successful corps included the I and II/ Army of the Potomac, known for their bravery;

the XXV, composed entirely of black troops and the XXII corps, which garrisoned the fortifications around Washington, D.C.

during most of the war and guarded the Union capital.

Corps were organized in the Confederate army November, 1862 and were

designated by numbers duplicated in the East and West but were often referred to by the name of their commander. Thus, the

II Corps in the East was called Jackson's Corps, even after he was killed. This corps endured some of the hardest marching

and heaviest fighting of the war. After their initial trial in the Civil War, corps became an integral part of the organization

of the U.S. Army in wartime.

DIVISION

In field armies on both sides in the Civil War, the division was the second

largest unit. In ascending order of size, units were: company, regiment brigade, division, corps. Theoretically,

company strength was 100; regiment, 1,000; brigade, 4,000; and division, 12,000. Occasionally, more often in the Confederate

army battalions of 2 to 10 companies were accepted into the ranks. In the Union army, the actual numbers, by the attrition

of war, were only 40-50% of those figures by 1863; the percentage was higher in the Confederate army, thanks to its system

of assigning recruits to existing regiments instead of creating new regiments.

In the Union armies the number of divisions in a corps varied from 2 to 4, though usually there were 3. In spring

1863, Maj. Gen. Joseph "Fighting Joe" Hooker ordered the army of the Potomac to wear Corps Badges, which led to designating

divisions by badges and by flags in red, white, and blue, for 1st, 2nd, and 3rd, divisions, respectively; the few 4th

divisions had green badges and flags; 5th divisions, orange. Without uniform badges and flags, the Confederates used

a less complicated system. Though they began by numbering their divisions, in a short time divisions, as well as other

army units, come to be known by their commanders' name.

The Union division were commanded by brigadier or major generals, and the frontage of an average 1863 Union division,

drawn up in double-rank line of battle with no skirmishers deployed, would have been just short of a mile. The Confederates

were more logical: with rare exceptions, brigadiers commanded brigades and major generals led division, and these units

were usually numerically superior to their Union counterparts. An extreme example: at one time Confederate Maj. Gen.

Ambrose P. Hill's famous Light Division had 7 brigades, giving it a strength of about 17,000.

| Total Contributions to the Union Military |

|

| Each state's total contribution to the Union military |

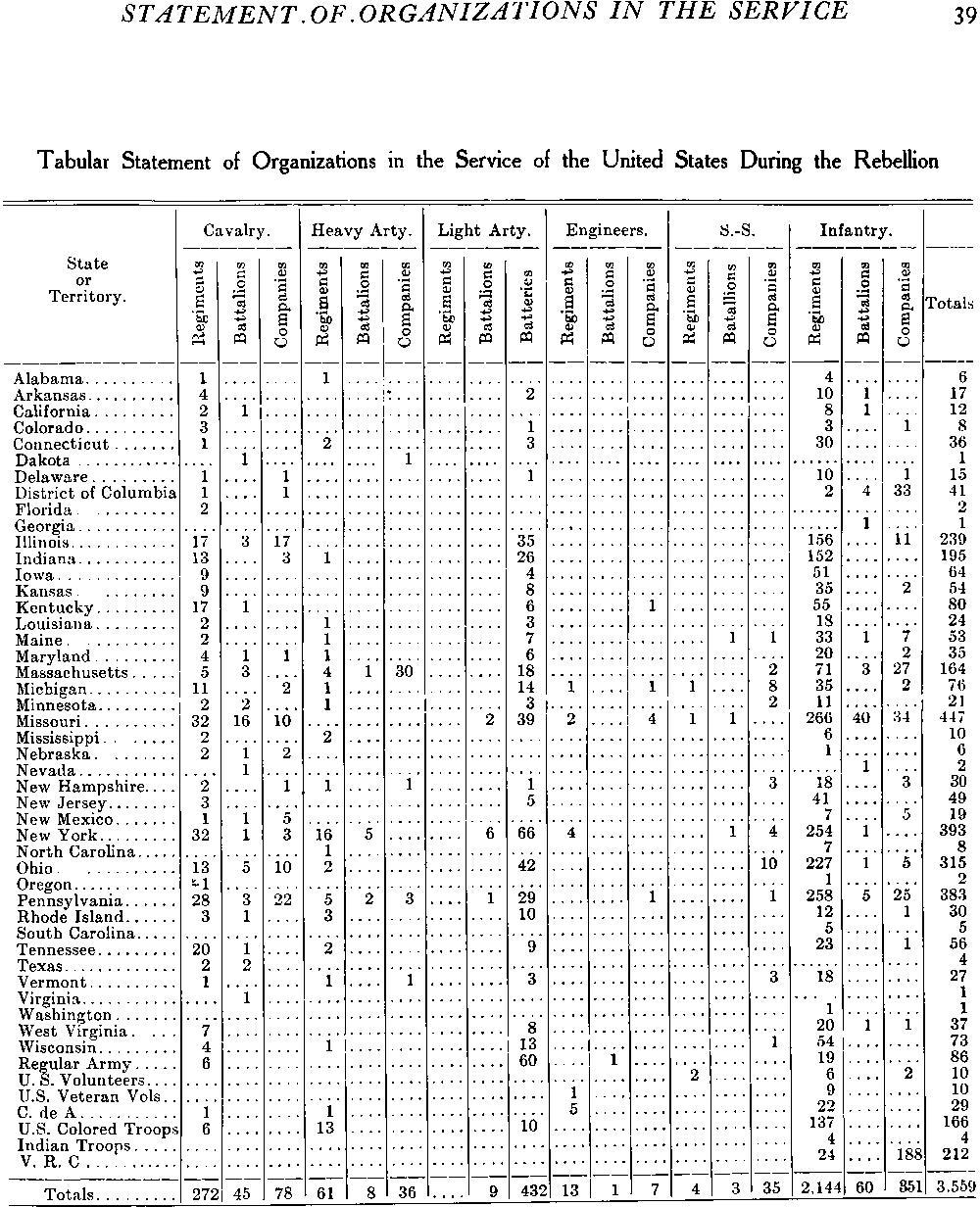

(Above) Dyer, Frederick H. A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion

(1908). Acclaimed Civil War statistician Dyer, in the table, indicates the total number of units--infantry, cavalry,

artillery, engineers, and sharpshooters--for each state, North and South, that supported the Union, and in the bottom right

corner is the grand total. While Dyer indicates the total Northern and Southern units that served in the Union military and concludes with the grand total, he also

includes the contributions of African-Americans, Native Americans, and Border States in an easy to read format. See also

Organization of Union

and Confederate Armies: Infantry, Cavalry, Artillery.

BRIGADE

The tactical infantry unit of the Civil War, the brigade generally consisted

of 4-6 regiments. However, it could have as few as 2 and later in the war, when consolidation of Confederate regiments became

common, some brigades contained remnants of as many as 15 regiments. There were 3 or 4 brigades to a division and several

divisions to a Corps. By definition, a brigadier general commanded a brigade. But colonels were often in charge

of brigades too small to justify a brigadier, and if the brigadier was absent, the senior colonel would act in his stead;

on occasion, temporary brigades organized for special purposes were commanded by colonels. The brigade's staff usually

comprised the brigadier general, his aide, the quartermaster, ordnance and commissary officers, and inspector, and one or

more clerks.

|

|

|

|

|

(Above) Napoleonic tactics made Civil War artillery crucial to the outcome of any

Civil War battle. Mass formations of soldiers, with great discipline, would march across open fields and into

shot and shell from artillery such as the pieces observed in the photo.

The brigade's effectiveness depended on regimental and company commanders

instructing their 1,000-1,500 men in the complicated maneuvers of the period, and on each regiment coordinating its movements

with the others under the brigade commander commanding.

Confederate brigades were known by the names of their commanders or former commanders, a much less prosaic system

than that of the Federals, but a very confusing one. For example. the unit of "Pickett's Charge" at Gettysburg shown in Steele's

American Campaigns as "McGowan's Brigade" was commanded by Pettigrew until 1 July '62 and then by Marshall. In this attack

Pettigrew is commanding "Heth's Division," Trimble is commanding "Pender's Division," Mayo is commanding "Brockenbrough's

Brigade," Marshall is commanding "McGowan's" or "Pettigrew's Brigade," Fry is commanding "Archer's Brigade," and Lowrance

is commanding "Scales's Brigade."

Some of the brigades became justly famous during the war. The Stonewall Brigade was one of Gen. R.E. Lee's best

units, as was Hood's Texas Brigade. Western Confederate brigades included the Orphan Brigade of Kentucky and the 1st

Missouri Brigade. On the Union side, the Iron Brigade earned fame in the Army of the Potomac, as did the Philadelphia

Brigade. Wilder's Lightning Brigade of mounted infantry combined infantry and cavalry tactics to become one of the best

Union units.

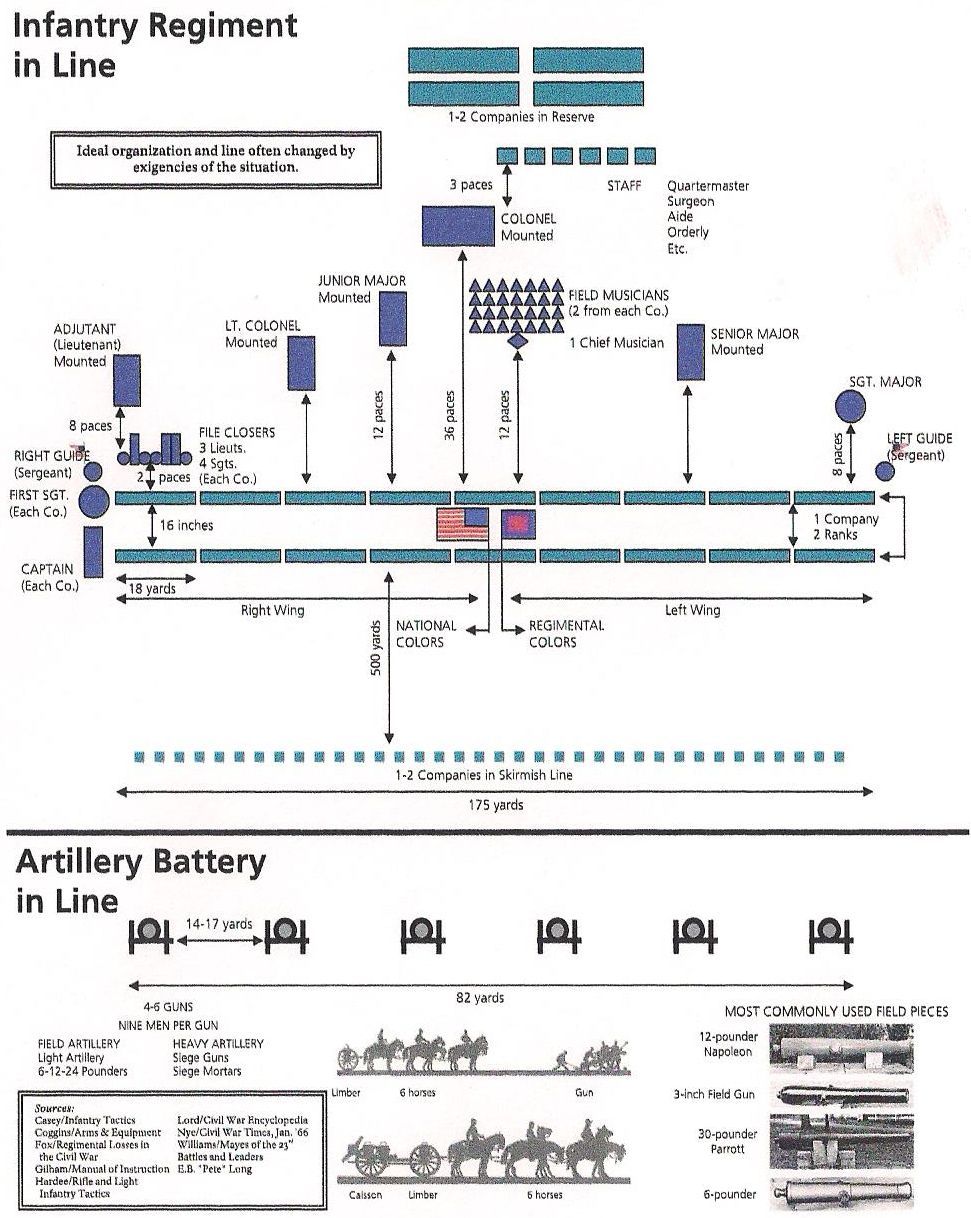

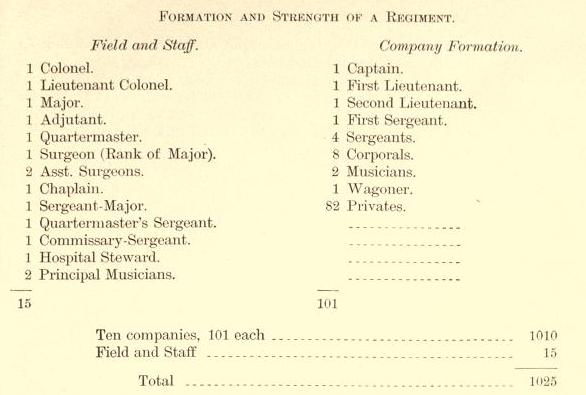

| Civil War Infantry Regiment chart |

|

| Civil War infantry regiment formation and structure, Fox, William F. |

REGIMENT

Infantry regiments were composed of 10 companies, except in the case of

the 12-company heavy artillery regiments that had been retrained as infantry. Cavalry regiments also had 12 companies. These

companies were lettered in alphabetical order, with the letter "J" omitted. There has been much erroneous theorizing as to

why the US Army has never had a "J" Company*. Battalions did not exist in the infantry regiments, but the "heavies" were

composed of three four company battalions, each commanded by a major.

Confederate regiments were organized in generally the same manner as the Federal, although some had

battalions (e.g., the 55th Ala.) and the 7th Ala. had two cavalry companies initially.

In the Union Army an infantry company had a maximum authorized strength of 101 officers and men, and

a minimum strength of 83. The company was allowed to recruit a minimum of 64 or a maximum of 82 privates. Other company positions

were fixed as follows: one captain, one first lieutenant, one second lieutenant, one first sergeant, four sergeants, eight

corporals, two musicians, and one wagoner. Company officers were elected in most volunteer units.

As Schiebert, the Prussian observer, points out, this was the only possible way of getting rapidly the

large number of troop leaders needed. By the second year of the war a system of examinations was instituted by both armies,

and incompetent officers could be eliminated (Schiebert, 39-40). Regimental headquarters consisted of a colonel, lieutenant

colonel, major, adjutant, quartermaster, surgeon (major), two assistant surgeons, and a chaplain. Regimental headquarters

noncommissioned officers were the sergeant major, quartermaster sergeant, commissary sergeant, hospital steward, and two principal

musicians. Authorized strength of an infantry regiment was a maximum of 1,025 and a minimum of 845. Since it was the Civil

War practice to organize recruits into new regiments rather than to send them to replace losses in veteran units, regimental

strengths steadily declined. According to Fiebeger the average company strength at Gettysburg was 32 officers and men per

company. Livermore gives these average regimental strengths in the Union army at various periods: Shiloh, 560; Fair Oaks,

650; Chancellorsville, 530; Gettysburg, 375; Chickamauga and the Wilderness, 440; and in Sherman's battles of May '64, 305.

According to Bigelow the average strength of Federal regiments at Chancellorsville was 433 and of Confederate regiments 409.

The North raised the equivalent of 2,047 regiments during the war of which 1,696 were infantry, 272

were cavalry, and 78 were artillery. Allowing for the fact that nine infantry regiments of the Regular Army had 24 instead

of the normal 10 companies, the total number of regiments would come to about 2,050, not including the Veteran Reserve Corps.

(Above figures from Phisterer, 23.) According to the computations of Fox, made before the Official Records had all been published,

the South raised the equivalent of 764 regiments that served all or most of the war. Using later data, and including militia

and other irregular organizations, Col. Henry Stone estimated an equivalent of 1,009 ½ Confederate regiments. (For exhaustive

study of Confederate strengths see Livermore.)

*As a former member of two branches of the military, and speaking

as a military historian, the army would not use the letter "J" because while in formation and while in battle,

commands, as shouted during the roar and rumble of shot and shell, could easily be misunderstood causing the

letter "J" to sound like "A". For example, imagine for a moment that you are a Civil War soldier and that, after your

24 hour forced march, you just arrived on the battlefield, exhausted in all senses, only to be welcomed by the

sounds and sights of battle. You are also starving and thirsty, sleep deprived, shoeless, experiencing body

aches and pains and a fever of 103, recovering from wounds of prior battles, and, moreover, in the presence of booming

artillery and the ringing of ears, screaming soldiers falling to their death, thundering musketry and smoke filled

atmosphere, you must reach deep within and muster every ounce of mental and physical strength humanly possible, and fight

for the your life, fight for the moment, and now you must distinguish whether you just heard the command, Company "A" or "J"

FORWARD! Or RETREAT!

Sources: Library of Congress; National Archives; National Park Service;

Official Records of the Union and Federal Armies; 1860 United States Census; Civil War Trust; US Army Center of Military History;

Dyer, Frederick H., A Compendium of the War of Rebellion (1908): Fox, William

F. Regimental Losses in the American Civil War (1889); Phisterer, Frederick. Statistical record of the armies of the United

States (1883); Hardesty, Jesse. Killed and died of wounds in the Union

army during the Civil War (1915) Wright-Eley Co.; C&O Canal

National Historical Park; Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park; Governor's Island National Monument; Harpers

Ferry National Historical Park; Mammoth Cave National Park; Springfield Armory National Historic Site; Richmond National Battlefield

Park; Shiloh National Military Park; Boatner III, Mark M. Civil War Dictionary; Faust

Patricia L. Ed. Historical Times Encyclopedia of the Civil War; Wolfe, Brendan. Military Organization

and Rank During the Civil War. Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 15 Aug. 2012. Web. 24 Nov. 2013.

Return to American Civil War Homepage

|

|

|