|

|

United States Cavalry History

Union and Confederate Cavalry History

U.S. Cavalry History

From Dragoons, Mounted Infantry, to Civil War Cavalry

| Cavalry History |

|

| Tracking the Federals. NPS. |

Introduction

The word dragoon originally meant mounted infantry,

referring to those who were both skilled horsemen and infantrymen, but usage of the term dragoon evolved gradually during

the 18th and 19th centuries. The United States dragoons fought in the American

Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and the Mexican-American War (1846-48), but would be known as cavalry during the American

Civil War (1861-65). Established in most European armies during the late 17th and early 18th centuries, dragoons were conventional

light cavalry units.

(Right) "Tracking the Federals." NPS. The Union cavalry was disadvantaged

at the start of the war because Northern soldiers had less comparative equestrian experience than their Southern counterparts.

While roads in the rural South were generally poor, horses were used daily for individual transportation, but carriages

and streetcars were more prevalent in the urbanized North. The explanation was rather simple, Southern communities were overwhelmingly

rural causing its citizens to rely heavily on the four-hoofed mammal. In 1860, for example, the South had only one city with

more than 100,000 citizens, New Orleans, but the North enjoyed eight cities with greater than 100,000 individuals, and collectively

the eight totaled more than 2,500,000. By late 1863, as veteran Union troops sat astride their mounts, the battlefields

were no longer touted as being Confederate owned, for the men in blue had demonstrated during the largest cavalry battle

on American soil, at Brandy Station, that they could now fight on par with their gray-clad Southern neighbors.

By

mid-nineteenth century, however, U.S. dragoons and mounted infantry units were being redesignated as cavalry.

Mounted infantrymen were trained equestrians who fought while dismounted, but cavalrymen, on the other hand, remained

on their mounts while in battle. By 1861, Union mounted forces were henceforth known as cavalry, but there were exceptions

as some Northern states continued to designate a small number of their units as mounted infantry or mounted rifles. While

the terms mounted infantry and mounted rifles were interchangeable, it is interesting to note, however, that many Southern

states, such as Tennessee, raised several "mounted infantry" and "cavalry" regiments

for the Union, while Northern states, New York for example, organized some "mounted rifles" and numerous "cavalry" units for

the Union. The primary reason was merely a cultural difference between the North and South and their preferences in words

and phrases.

While dragoons are presently represented in some militaries for ceremonial purposes, cavalry

has continued to evolve on a global scale. The United States military currently employs a wide variety of cavalry,

from air to mechanized units, that trace their origin to the dragoons who served and fought under George Washington in hopes

of securing a nation for thirteen fledgling colonies.

| Civil War Cavalry Battle |

|

| Union and Confederate Cavalry Charge |

| Revolutionary War Dragoons |

|

| Continental Light Dragoon |

(About) Battle of Westport, also known as "Gettysburg of the West,"

fought on October 23, 1864, in modern Kansas City, Missouri, as depicted in mural in Missouri State Capitol. An often overlooked

Civil War battle involving nearly 30,000 cavalrymen in the West, it pitted a Union contingent, mainly of Kansas and Missouri,

numbering some 22,000 cavalry, against a much smaller Confederate force of Missouri and Arkansas cavalry totaling 8,500.

Union forces under Major General Samuel R. Curtis decisively defeated an outnumbered Confederate army under Major General

Sterling Price. This engagement was the turning point of Price's Missouri Expedition, forcing his army to retreat and ending

the last significant Confederate operation west of the Mississippi River. This battle was one of the largest fought in

the West, with more than 30,000 troops engaged. Although Union casualties in killed and wounded totaled 1,500, and the

Confederates suffered equal losses numbering 1,500, Union casualties were merely 7% of its forces engaged, while

the Confederate force lost nearly 18% of its entire army.

Dragoons, Mounted Infantry, and Cavalry

In late 1776 George Washington realized the need for a mounted component

of the military. In January 1777 four regiments of light dragoons were raised. Short term enlistments were abandoned and the

dragoons served for three years, or "the war." They participated in most of the major engagements of the American Revolutionary

War, including the battles of White Plains, Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, Germantown, Saratoga, Cowpens, and Monmouth, as

well as the Yorktown campaign.

(Right) Private, Continental Light Dragoons (1777-1782). National Park Service.

During the War of 1812, the U.S. organized two regiments of light dragoons.

The 1st United States Dragoons later explored Iowa after the Black Hawk Purchase (1832) placed the area under U.S. control.

In the summer of 1835, the regiment traversed a trail along the Des Moines River and established outposts from present-day

Des Moines to Fort Dodge. While dragoons were active in the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), the

remaining two dragoon regiments would be redesignated as cavalry in 1861.

The "United States Regiment of Dragoons" was organized by an Act of Congress approved on March

2, 1833. It became the "First Regiment of Dragoons" when the Second Dragoons was raised in 1836. With the outbreak of the

Civil War and the War Department's desire to redesignate and reorganize its mounted units, its designation was changed to

"First Regiment of Cavalry" by another Act of Congress on August 3, 1861. Its Headquarters was initially established

at Jefferson Barracks, near St. Louis, Missouri. In the spring of 1855, two new regiments of cavalry, the First and Second

Cavalry, were authorized. One of these was named the "First Cavalry Regiment”, under the command of Lt. Col. Edwin

Vose Sumner (he previously served with the First Dragoons), the first regular American military unit to bear that name.

Mounted infantry were soldiers who rode horses instead of marching, but fought on foot. The original

dragoons were essentially mounted infantry.

In 1861 the two existing U.S. Dragoon regiments were redesignated as the 1st and 2nd Cavalry.

This reorganization did not affect their role or equipment, although the traditional orange uniform braiding of the dragoons

was replaced by the standard yellow of the Cavalry branch. This marked the official end of dragoons in the U.S. Army, although

certain modern units trace their origins to the historic dragoon regiments.

| Cavalry History |

|

| Confederate Cavalryman with Double Barrel Shotgun |

| Cavalry History |

|

| Union Cavalryman with three Remington revolvers |

Civil War Cavalry

"And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death,

and Hell followed with him." Revelations 6:8

The Union began the Civil War with five Regular mounted regiments: the 1st and 2nd

U.S. Dragoons, the 1st Mounted Rifles, and the 1st and 2nd Cavalry. These were renumbered the 1st through 5th U.S. Cavalry

regiments, respectively, and a 6th was recruited. While Union mounted units since 1861

were organized and referred to as cavalry, by 1864 many of the units were merely cavalry in designation but dismounted

infantry in operation, because although they rode horses, they dismounted and fought as infantry during battle. The mounted infantry units would serve and fight like dragoons during the conflict, but in 1864 cavalry

regiments also fought as dismounted infantry. As mounted infantrymen fought while dismounted, one soldier

was responsible for securing four horses during battle, allowing three soldiers to engage the enemy with an assortment

of rifles.

(Left) Union cavalryman armed to the teeth while posing with issued uniform, three Remington

revolvers, two Bowie knives, and a Springfield rifle-musket. Knives were usually discarded later in the war, and replaced

with additional revolvers. Only posing. Because of the placement of the knives and the fact that this trooper was carrying

three revolvers, it indicates that, although dated ca. 1861-1865, this photo was most likely taken ca. 1863-'65. This

seasoned cavalryman also carried his Union furnished Springfield, which remained popular with many troopers during the war,

particularly when cavalry generally fought while dismounted as the conflict progressed. Courtesy Library of Congress, Liljenquist

Collection. (Right) Confederate horseman armed with double barrel shotgun and D-Guard Bowie Knife, but revolvers and a rifle

are absent, either because he only had the shotgun or because he was merely posing for his moment. Nevertheless, while mounted,

at short distances, the double barrel shots could hit a moving target a lot easier than a rifle or revolver.

The U.S. Army entered into the Civil War in 1861 with scarcely

a cavalry force, save five regiments. By the end of the war, 272 cavalry regiments were formed in the Union army and 137 in the Confederate army. Initially, raising a single cavalry regiment for the Union was met

with mixed resistance in Congress because of training and financial reasons:

- Training for the cavalryman was extensive and could span nearly two years,

but politicians in Washington were divided on the length of the conflict, with many expecting a Union victory in only 90

days.

- Cost for organizing and equipping a cavalry regiment of 1,000

horsemen in 1860 was $300,000, and to field and maintain the unit cost $100,000 annually.

The Union cavalry was disadvantaged

at the start of the war because Northern soldiers had less comparative equestrian experience than their Southern

counterparts, and while the roads in the rural South were generally poor, horses were used daily for individual

transportation than they were for the carriages and streetcars of the urbanized North. The explanation was rather simple,

Southern communities were overwhelmingly rural causing its citizens to rely heavily on the four-hoofed mammal. In

1860, for example, the South had only one city with more than 100,000 citizens, New Orleans, but the North enjoyed eight cities

with greater than 100,000 individuals, and collectively the eight totaled more than 2,500,000. The North owned 20 of the 21

most populated cities in the nation in 1860, with the Southern city of Charleston ranking 22 with 40,522 residents. New Orleans

would continue to grow from 168,675 in 1860 to its peak population of 627,525 in 1960, but after 100 years

to the date, the city would decline every U.S. census from 1970 onward, plummeting to 343,829 according to the 2010 U.S.

Census.

In addition, over half (104 out of 176) of the experienced U.S. Army cavalry

officers had resigned their commissions to fight for the Confederacy. One advantage the Union horseman had over his opponent

was the centralized horse procurement organization of the army, relieving him of any responsibility for replacing an injured

horse. Commanders often tried to procure specific breeds for their men, with the Morgan being a particular favorite within

the Army of the Potomac. Famous Morgan cavalry mounts from the Civil War included Sheridan's "Rienzi" and Stonewall Jackson's

"Little Sorrel".

Although there were partisan and guerrilla forces, there were only two

preeminent mounted forces during the Civil War:

- Cavalry were forces that fought principally on horseback, armed with carbines,

pistols, and especially sabers. Only a small percentage of Civil War forces met this definition—primarily Union mounted

forces in the Eastern Theater during the first half of the war. Confederate forces in the East generally carried neither carbines

nor sabers. A few Confederate regiments in the Western Theater carried shotguns, especially early in the war.

- Mounted infantry were forces that moved on horseback but dismounted for fighting

on foot, armed principally with rifles. In the second half of the war, most of the units considered to be cavalry actually

fought battles using the tactics of mounted infantry. An example of this was the celebrated "Lightning Brigade" of Col. John

T. Wilder, which used horses to quickly arrive at a battlefield such as Chickamauga, but they deployed and fought using standard

infantry formations and tactics. By contrast, at the Battle of Gettysburg, Federal cavalry under John Buford also dismounted

to fight Confederate infantry, but they used conventional cavalry tactics, arms, and formations. There were some state units

designated as dragoons in the war, but they performed as mounted infantry.

| Civil War Cavalry History with Weapons |

|

| Typical Civil War Cavalry Weapons |

| US Cavalry History |

|

| Civil War Cavalry Charge With Sabers Drawn |

(Above) Typical Civil War Cavalry Accoutrements. Among the revolvers issued

to Union Cavalry during the Civil War, was the Colt 1860 Army Revolver, but there were some who favored the lighter Colt

1851 Navy Revolver, as seen above, including Famous "Navy" users included Wild Bill Hickok, John Henry "Doc" Holliday, Richard

Francis Burton, Ned Kelly, Bully Hayes, Richard H. Barter, Robert E. Lee, Nathan B. Forrest, John O'Neill, Frank Gardiner,

Quantrill's Raiders, John Coffee "Jack" Hays, "Bigfoot" Wallace, Ben McCulloch, Addison Gillespie, John "RIP" Ford, "Sul"

Ross and most Texas Rangers prior to the Civil War. (Right) The final effort by Porter's defenders at Gaines Mill was a desperate

cavalry charge. A Confederate victory led by Gen. Robert E. Lee, the Battle of Gaines Mill was contested during the Seven

Days Battles of the Peninsula Campaign. Artist William Trego memorialized the dramatic twilight scene in this postwar painting.

NPS.

Horses enabled the cavalry forces significant mobility, and in some

operations tested the limits of both man and mount, such as Jeb Stuart's raid on Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, in 1862,

where his troopers marched 80 miles in 27 hours. Such excesses were extremely damaging to the readiness of the units

and extensive recovery periods were required. Stuart, during the Gettysburg Campaign the following year, resorted to procuring

replacement horses from local farmers and townspeople during his grueling trek northward around the Union army. In York County,

Pennsylvania, following the Battle of Hanover, his men appropriated well over 1,000 horses from the region. Many of these

untrained new mounts proved a hindrance during the subsequent fighting at East Cavalry Field during the battle of Gettysburg.

Even though the roles and functions often overlapped, Civil War

cavalry was responsible for five major missions:

- Reconnaissance and screening. Reconnaissance meant locating and maintaining

contact with the enemy. Screening was covering and concealing the movements of your own army from the enemy’s reconnaissance

attempts.

- Defensive, delaying actions. Defensive actions was often covering the flanks

and rear of your army in battle and threatening those of your enemy.

- Pursuit and harassment of defeated enemy forces.

- Offensive operations. Offensive actions included shock charges against

enemy positions or lines and ascertaining weaknesses in hopes of breaking them, to produce a rout, or,

when your own army is withdrawing, to delay the pursuit.

- Long-distance raiding against enemy lines of communications, supply depots,

railroads, etc. Raiding included locating and capturing enemy supplies such as wagons trains, and the raids increased

as the war continued.

| Union Cavalry during the Civil War |

|

| Federal cavalry column along the Rappahannock River, VA., 1862. Archives.gov |

| Confederate Cavalry Painting |

|

| Confederate Cavalry Charging Union Camp. NPS. |

Early in the war, Union cavalry forces were often used merely as pickets,

outposts, orderlies, guards for senior officers, and messengers. The first officer to make effective use of the Union cavalry

was Major General Joseph Hooker, who in 1863 consolidated the cavalry forces of his Army of the Potomac under a single commander

named George Stoneman. A rather determined cavalryman, Stoneman was the only cavalry commander of the Civil War

to have been relieved of command, bemoaned by both Lt. Gen. Grant and Secretary of War Stanton, followed by reassignment

to commanding general of a cavalry division, only to become the highest ranking Union officer to serve as a prisoner-of-war,

then afterwards be assigned one of the most daring missions of the war by Grant himself, accomplish his personal

objective of destroying the most vital salt producing facility in the Confederacy, and then be praised by President Johnson

as being one fine cavalry general. (See also Second Battle of Saltville.)

As the war progressed, the value of cavalry was eventually realized (primarily

for non-offensive missions), and numerous state volunteer cavalry regiments were added to the army. While initially reluctant

to form a large cavalry force, the Union eventually fielded some 258 mounted regiments and 170 unattached companies, of differing

enlistment periods, throughout the war and suffered 10,596 killed and 26,490 wounded during the struggle.

Although they most often fought on foot—particularly as the Civil

War progressed—cavalry units typically looked for firearms that would be easy to reload from astride a galloping

horse. Cavalry in both the Union and the Confederate armies employed a variety of breech-loading, single-shot, and rifle-barreled

weapons known as carbines. The carbines, because their barrels were several inches shorter than the rifle-muskets the infantry

carried, also had a shorter range. In addition, the cavalry weapons had a brutal recoil when fired, and—despite their

advantages in loading—most still required the cavalryman to navigate a tiny cap in order to fire. Confederate cavalry

often brought sawed-off shotguns and cut-down hunting rifles from home. Others used the standard infantry rifle-muskets, though

the longer barrels were awkward and muzzle-loading was rather difficult on horseback.

Some mounted forces used traditional infantry rifles, because they either

preferred the rifle-musket or were issued it. The principal item of both mounted infantry and cavalry was his horse,

but both horsemen had his preference of weapons. Cavalrymen, particularly in the North, were frequently armed with

three weapons, the carbine, revolver, and saber, but in the South, the preferred weapons included the rifle, shotgun,

and few revolvers.

- Carbines, with a shorter barrel than a rifle, were less accurate, but easier

to handle on horseback. Most carbines were .52- or .56-caliber, single-shot breech-loading weapons. They were manufactured

by several different companies, but the most common were the Sharps, the Burnside, and the Smith. Late in 1863, the seven-shot

Spencer repeating carbine was introduced, but it was rarely deployed. Confederate forces were able to use captured breechloaders

but were unable to duplicate the metallic cartridges needed by the Spencer.

- Sabers were used more frequently by Northern cavalrymen, but they were only

useful after all other weapons had been spent and only when the opposing armies had collided. Confederate riders

had long since shed the impractical heavy blades for more useful pieces such as revolvers, and that meant obtaining and carrying

as many revolvers as possible. Some Southern dandies were known to wield as many as four or more six-shooters, and at close

range that made for twenty-four shots without reloading a single time.

- Pistols, which Southern cavalrymen generally preferred over sabers, were

usually six-shot revolvers, in .36- or .44-caliber, from Colt or Remington. They were useful only in close fighting because

the shot deviated beyond the range of 50 yards. It was common for cavalrymen to carry two revolvers, for extra

firepower, and John Mosby's troopers often carried four each. To offset any restriction caused by the pistol, Confederate

troops were known to have a fondness for shotguns, single and double barrel, which could disperse hot metal in a devastating

swath of 50-100 yards.

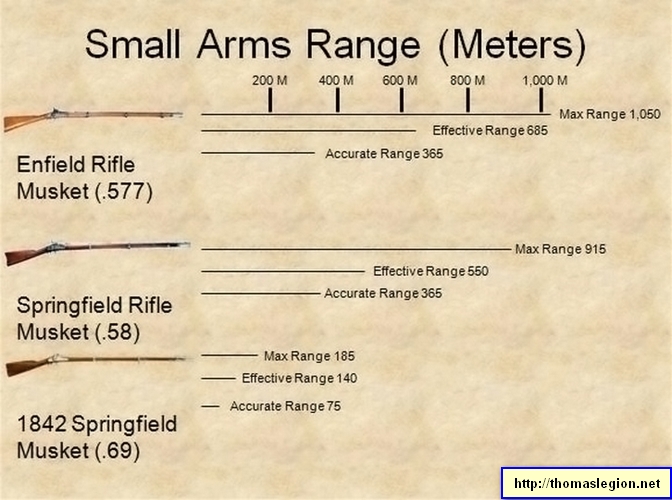

| Typical Civil War Cavalry Weapons and Range Chart |

|

| Civil War cavalry rifles and accurate, effective, and max ranges |

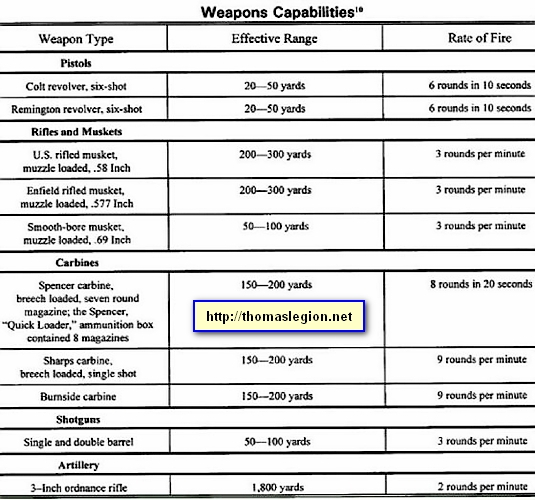

| Civil War Cavalry Weapons and Capabilities |

|

| Types of Civil War cavalry weapons and their capabilities |

(Left) Civil War Cavalry Weapons and Capabilities: Type of Weapon, Effective

Range, and Rate of Fire. (Right) Widely used Union and Confederate weapons and their accurate, effective, and maximum ranges.

Although infantry regiments employed these rifles, they remained the firearm of choice for some Union and Confederate cavalrymen,

particularly when cavalry fought more as mounted infantry as the conflict continued. The preference for the dismounted soldier was

due mainly to the effective range of the gun, which was significantly greater than carbines with their shorter barrels.

While the lists of firearms includes many of the small arms that the Union

and Confederate cavalries were furnished, it also shows an inventory of typical weapons employed during the Civil War. Effective

range is the maximum distance at which a weapon may be expected to be accurate and achieve the desired effect. Rate of fire

is the frequency at which a specific weapon can fire, and it is measured in rounds per minute (RPM)(round/min), unless otherwise

stated.

How was the effective range and rate of fire achieved by the cavalryman?

Extensive training enabled the cavalry soldier the necessary skill, knowledge, and experience required to achieve the rate

of fire and the effective range during battle.

Three Factors of Accuracy. There were

three factors which determined whether or not the projectile hit its target at the effective range: the cavalryman, meaning

the shooter, the firearm, and environmental conditions. A negative condition existing in any of the three factors, or

variables, will determine whether or not an effective hit is realized. If, for example, the soldier erred, or the rifle

malfunctioned, or it rained, the odds of hitting within the weapon's effective range were reduced.

Cavalry small arms with accurate, effective, and maximum ranges. A trained cavalryman was expected to strike

the enemy between the accurate and effective ranges on the chart. What is the difference between accurate, effective, and

maximum range? To keep it simple, imagine a large round target with a bullseye.

- Accurate range is defined as the distance which a projectile will travel

to hit center, the bullseye.

- Effective range is the distance which a projectile will travel to hit the

target, not the bullseye.

- Maximum range is the distance the projectile will field to cause a casualty,

meaning, if it (actually) hit it would wound or kill the enemy.

| Union and Confederate Cavalry |

|

| The Battle of Upperville. Harper's Weekly, July 18, 1863. |

| U.S. Dragoons in Mexican-American War |

|

| U.S. Dragoons slashing through Mexican lines in Mexican War (1849-48). NPS. |

Question and Answer Session: Dragoons, Mounted Infantry, and Cavalry

What was the major difference between dragoons and mounted infantry?

Dragoons were issued the musketoon, a shorter-barreled version of the musket, while mounted infantry were

generally issued the standard army musket. While the musketoon was easier to carry while astride the mount, the shorter barrel

had a shorter effective range.

What was the difference between mounted infantry and cavalry?

While both rode swift chargers, mounted infantry were usually equipped with the muzzle-loading

rifle-musket, making it nearly impossible to reload on horseback, so it was necessary to dismount and engage the enemy. The

dismounted infantryman with the rifle-musket could fire 3 rounds per minute. Cavalry were issued carbines capable

of firing 10-20 rounds per minute, and many cavalrymen carried into battle two or more revolvers, increasing the rate

of fire while reducing the reloading time.

What was foot cavalry?

Foot cavalry was an oxymoron coined to describe the rapid movements of infantry troops serving

under Confederate General Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson during the Civil War.

What were some significant differences between Union and

Confederate cavalry?

Southern cavalrymen initially held an advantage in the

saddle due to their predominately rural lifestyle requiring horses for daily living, but Union cavalrymen were battle-hardened

and fought on par with its Southern chargers by the summer of 1863. The Federal government supplied horses for its cavalry,

but Confederate horsemen provided their own steeds for service. If the Rebel trooper needed another mount, he had to

provide it, too, or he would subsequently serve in the infantry. Union cavalry enjoyed an array of superior quality carbines,

while Confederate troops carried from Southern manufactured carbines, rifled-muskets, several revolvers, shotguns,

to captured small arms into the fray.

What were the advantages of the variety of weapons used by the cavalry?

Carbines were easy to reload, enjoyed a high rate of fire, but its shorter barrel limited its

effective range to 150-200 yards. Revolvers, the six-shooters, contrary to romanticized history, were only effective

at short ranges of 20 to 50 yards, making it a last line of defense. The cumbersome Enfield Pattern 1853 rifle-musket

and Springfield Model 1861 rifle-musket had to be reloaded after each shot, but both enjoyed an effective killing field

of more than 400 yards, giving it an advantage in distance only. Daunting shotguns joined the ranks of revolvers and were

employed at close range with a less than stellar span of 50-100 yards.

When was the last U.S. cavalry charge?

The last horse-mounted cavalry charge by a U.S. Cavalry unit took place

on the Bataan Peninsula, in the Philippines. The 26th Cavalry Regiment of the Philippine Scouts executed the charge against

Japanese forces near the village of Morong on January 16, 1942.

Losses for United States Regular Cavalry Regiments during the Civil War

|

No. of Com-panies Orga-nized. |

Killed and Died of Wounds |

Aver-age loss per Com-pany |

Died of Disease, Accidents, in Prison, etc. |

Total Deaths from all causes. |

Average per Company |

|

| Officers |

Enlisted |

Total |

Officers |

Enlisted |

Total |

Officers |

Enlisted |

Grand Total |

| 1st Cavalry |

12 |

9 |

73 |

82 |

6.8 |

2 |

91 |

93 |

11 |

164 |

175 |

14.6 |

|

| 2d Cavalry |

12 |

5 |

73 |

78 |

6.5 |

3 |

92 |

95 |

8 |

165 |

173 |

14.4 |

|

| 3d Cavalry |

12 |

2 |

30 |

32 |

2.7 |

3 |

105 |

108 |

3 |

135 |

140 |

11.7 |

|

| 4th Cavalry |

12 |

3 |

59 |

62 |

5.2 |

1 |

108 |

109 |

4 |

167 |

171 |

14.2 |

|

| 5th Cavalry |

12 |

7 |

60 |

67 |

5.6 |

2 |

90 |

92 |

9 |

150 |

159 |

13.2 |

|

| 6th Cavalry |

12 |

2 |

50 |

52 |

4.3 |

1 |

106 |

107 |

3 |

156 |

159 |

13.2 |

(About) United States Cavalry. Table of losses sustained by each of the

Regular Cavalry regiments during 1861-65. Compiled by Captain W. P. Evans, 19th U.S. Infantry.

| Union Cavalry at Bull Run |

|

| Federal Cavalry at Sudley Springs after the first Battle of Bull Run. Archives.gov |

Aftermath

While U.S.

cavalry was armed with rifles and sabers, the 1860s saw cavalry transition to more rapid firing small arms, and the

exchanging of the ceremonial sabers for two or more pistols for additional firepower. Cavalry would evolve into a strike force

with the capability of unleashing quick, devastating blows against the enemy. During the 1870s, particularly during the

Indian wars, U.S. cavalry consisted of many battle-hardened veterans of the Civil War who were skilled equestrians,

rifleman, and pistoliers, and they could maintain an unmatched rate of fire during battle. From the 1870s to 1890s,

new technology enabled advancements in weaponry which would alter the role of cavalry. New inventions meant that cavalry would

engage the enemy under the fighting principles of "distance and shielding."

With the invention of "smokeless powder" in

the 1880s, U.S. cavalry abandoned "black powder" and adopted tactics to fully utilize the new invention. While

black powder produced a smoke cloud obscuring the rifleman's view, it exposed the position of even the best sniper. With

smokeless powder, troopers could dismount and fully appreciate greater distances without compromising their position.

Shielding, which optimized stealth, allowed the trooper to dismount and engage the enemy from a ridge or behind a tree.

Smokeless powder would cause major changes in the role and tactics of U.S. cavalry.

Evolution

The United States Cavalry was the designation of the mounted force of the U.S. Army from the late 18th to the early 20th

century. The Cavalry branch was absorbed into the Armor branch in 1950, but the term "Cavalry" remains in use in the U.S.

Army for certain armor and aviation units historically derived from cavalry units.

Originally designated as United States Dragoons, the forces were patterned after cavalry units employed during the Revolutionary

War. The traditions of the U.S. Cavalry originated with the horse-mounted force which played an important role in extending

United States governance into the Western United States after the American Civil War.

Immediately preceding World War II, the U.S. Cavalry began transitioning to a mechanized, mounted force. During World

War II, the Army's cavalry units operated as horse-mounted, mechanized, or dismounted forces (infantry). The last horse-mounted

cavalry charge by a U.S. Cavalry unit took place on the Bataan Peninsula, in the Philippines. The 26th Cavalry Regiment of

the Philippine Scouts executed the charge against Japanese forces near the village of Morong on January 16, 1942.

The U.S. Cavalry branch was absorbed into the Armor branch as part of the Army Reorganization Act of 1950. The Vietnam

War saw the introduction of helicopters and operations as an airborne force with the designation of Air Cavalry, while mechanized

cavalry received the designation of Armored Cavalry.

Today, cavalry designations and traditions continue with regiments of both armor and aviation units that perform the

cavalry mission. The 1st Cavalry Division is the only active division in the United States Army with a cavalry designation.

The division maintains a detachment of horse-mounted cavalry for ceremonial purposes.

See also:

Sources: Coggins, Jack. Arms and Equipment of the Civil War. Doubleday &

Company, New York, 1962; Longacre, Edward G. The Cavalry at Gettysburg. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986. ISBN

0-8032-7941-8; Longacre, Edward G. General John Buford: A Military Biography. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing, 1995.

ISBN 0-938289-46-2; Longacre, Edward G. Lee's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002. ISBN 0-8117-0898-5; Longacre, Edward G. Lincoln's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted

Forces of the Army of the Potomac. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000. ISBN 0-8117-1049-1; Longacre, Edward G., and

Eric J. Wittenberg. Unpublished remarks to the Civil War Institute, Gettysburg College, June 2005; Mackey, Robert R. The UnCivil

War: Irregular Warfare in the Upper South, 1861-1865. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8061-3624-3; Miller,

Francis Trevelyan. The Cavalry, Part IV, A photographic History of the Civil War. Castle Books, New York, 1957; Nosworthy,

Brent. The Bloody Crucible of Courage, Fighting Methods and Combat Experience of the Civil War. New York: Carroll and Graf

Publishers, 2003. ISBN 0-7867-1147-7; Starr, Stephen Z. The Union Cavalry in the Civil War. Vol. 1, From Fort Sumter to Gettysburg

1861–1863. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0-8071-3291-3; Starr, Stephen Z. The Union

Cavalry in the Civil War. Vol. 2, The War in the East from Gettysburg to Appomattox 1863–1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana

State University Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0-8071-3292-0; Starr, Stephen Z. The Union Cavalry in the Civil War. Vol. 3, The War

in the West 1861–1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0-8071-3293-7; Urwin, Gregory J.

W. The United States Cavalry; An Illustrated History. Blandford Press, Poole Dorset, 1983; Wills, Brian Steel. The Confederacy's

Greatest Cavalryman: Nathan Bedford Forrest. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1992. ISBN 0-7006-0885-0; Wittenberg, Eric

J. Glory Enough For All: Sheridan's Second Raid and the Battle of Trevilian Station. Washington, DC: Brassey's, Inc., 2001.

ISBN 1-57488-468-9; Wittenberg, Eric J. The Battle of Brandy Station: North America's Largest Cavalry Battle. Charleston,

SC: The History Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-59629-782-1; National Park Service; Library of Congress; National Archives; Official

Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; Carleton, James Henry, author, Pelzer, Louis, editor, The Prairie Logbooks: Dragoon

Campaigns to the Pawnee Villages in 1844, and to the Rocky Mountains in 1845, University of Nebraska Press, 1983; Hildreth,

James, Dragoon Campaigns To The Rocky Mountains: A History Of The Enlistment, Organization And First Campaigns Of The Regiment

Of U. S. Dragoons 1836, Kessinger Publishing, LLC., 2005; Starry, Donn A., General. "Mounted Combat In Vietnam." Vietnam Studies;

Department of the Army; First printing 1978; Connecticut Adjutant General's Office (1889). Record of service of Connecticut

men in the I. War of the Revolution, II. War of 1812, III. Mexican War. Hartford, Connecticut: Case, Lockwood & Brainard;

Heitman, Francis Bernard (1968) [1903]. Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army, From Its Organization,

September 29, 1789, to 2 March 1903 I. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co.; Subbs, Mary Lee; Connor, Stanley Russell. ARMOR-CAVALRY

Part I: Regular Army and Army Reserve. 69-60002: United States Army Center of Military History, 1969; archives.gov; history.army.mil;

nps.gov; loc.gov.

|

|

|