|

|

Introduction

Maryland was one of the Thirteen Colonies and on April 28, 1788, by

ratifying the United States Constitution, it was admitted to the Union as the 7th U.S. state.

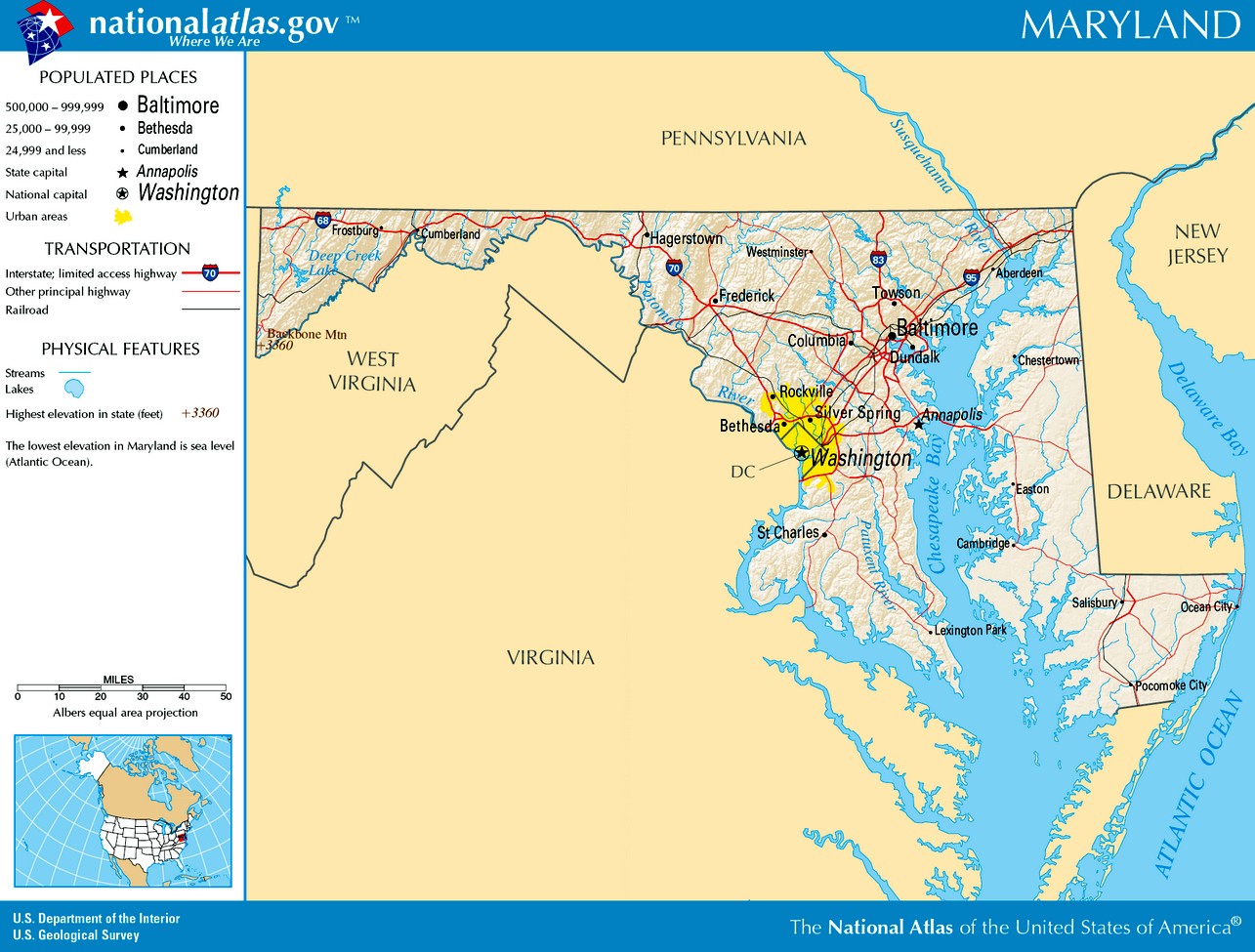

Maryland is a U.S. state located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United

States, bordering Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north;

and Delaware to its east. Maryland was the seventh state to ratify the United States Constitution, and has three occasionally

used nicknames: the Old Line State, the Free State, and the Chesapeake Bay State.

In 1498 the first European explorers sailed along the Eastern Shore,

off present-day Worcester County. In 1524 Giovanni da Verrazzano, sailing under the French flag, passed the mouth of Chesapeake

Bay. In 1608 John Smith entered the bay. The first European settlements were made in 1634, when the English arrived in significant

numbers and created a permanent colony. Maryland was notable for having been established with religious freedom for Catholics.

Like other colonies of the Chesapeake Bay, its economy was based on tobacco as a commodity crop, cultivated primarily by African

slave labor, although many young people came from the British Isles as indentured servants in the early years.

| Maryland Civil War History |

|

| Province of Maryland Map |

The Province of Maryland was an English and later British colony in North

America that existed from 1632 until 1776, when it joined the other twelve of the Thirteen Colonies in rebellion against Great

Britain and became the U.S. state of Maryland.

The province began as a proprietary colony of the English Lord Baltimore,

who wished to create a haven for English Catholics in the new world at the time of the European wars of religion. Although

Maryland was an early pioneer of religious toleration in the English colonies, religious strife among Anglicans, Puritans,

Catholics, and Quakers was common in the early years, and Puritan rebels briefly seized control of the province. In 1689,

the year following the Glorious Revolution, John Coode led a Protestant rebellion that expelled Lord Baltimore from power

in Maryland. Power in the colony was restored to the family in 1715 when Charles Calvert, 5th Baron Baltimore, swore publicly

that he was a Protestant. See also Lord Baltimore: Founder of Maryland.

Despite early competition with the colony of Virginia to its south,

and the Dutch colony of New Netherland to its north, the Province of Maryland developed along very similar lines to Virginia.

Its early settlements and populations centers tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into the

Chesapeake Bay and, like Virginia, Maryland's economy quickly became centered around the farming of tobacco for sale in Europe.

The need for cheap labor, and later with the mixed farming economy that developed when tobacco prices collapsed, led to a

rapid expansion of indentured servitude and, later, forcible immigration and enslavement of Africans.

The Province of Maryland was an active participant in the events leading

up to the American Revolution, and echoed events in New England by establishing committees of correspondence and hosting its

own tea party similar to the one that took place in Boston. By 1776 the old order had been overthrown, as Marylanders signed

the Declaration of Independence, forcing the end of British colonial rule.

In 1776, during the American Revolution, Maryland became a U.S. state.

After the war, numerous planters freed their slaves as the economy changed. In 1839, the United States' first passenger railway

service opened between Baltimore and nearby Ellicott City. As the railway expanded westward to Cumberland and Chicago, it

competed for business with the earlier 189 miles Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and the National Road. The United States Naval

Academy was founded in Annapolis in 1845, and the Maryland Agricultural College was chartered in 1856, growing eventually

into the University of Maryland.

Although still a slave state in 1860, by that time nearly half the black

population was already free, due mostly to manumissions after the American Revolution. Maryland was among the Border States that remained in the Union during the American Civil War (1861-1865).

Approximately 65,000* Maryland men joined the Union military during

the Civil War, while approximately 30,000 joined the Confederate Army. To help ensure Maryland's inclusion in the Union, Abraham

Lincoln suspended several civil liberties, including the writ of habeas corpus, an act deemed illegal by the Maryland native,

Chief Justice Roger Taney of the United States Supreme Court.

Lincoln ordered U.S. troops to place artillery on Federal Hill to threaten

the city of Baltimore, and helped ensure the election of a new pro-Union governor and legislature. Lincoln ordered certain

pro-South members of the state legislature and other prominent men jailed at Fort McHenry, including the Mayor of Baltimore,

George William Brown. The grandson of Francis Scott Key was included in those jailed. Historians continue to debate the constitutionality

of these actions taken during the crisis of wartime. The Thomas Viaduct, which crosses the Patapsco River on the B&O Railroad,

was considered so strategically important that Union troops were assigned to guard it throughout the entirety of the war.

Because Maryland remained in the Union, it was exempted from the abolition

provisions of the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, which applied only to states in rebellion. In 1864 the state held a constitutional

convention that culminated in the passage of a new state constitution. Article 24 of that document abolished slavery. In 1867,

following passage of constitutional amendments that granted voting rights to freedmen, the state extended suffrage to non-white

males.

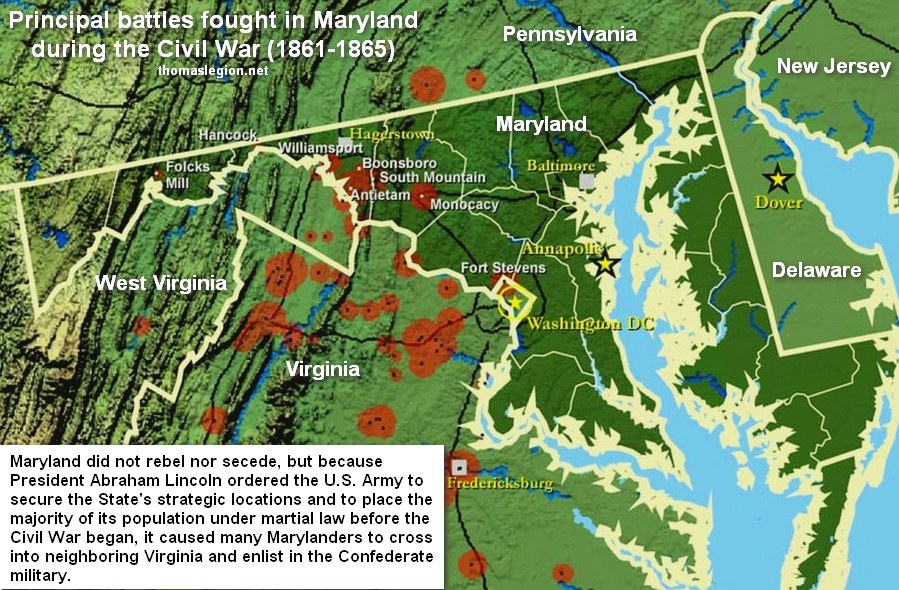

| Map of Maryland Civil War Battles |

|

| Maryland Civil War History and Map of Battlefields |

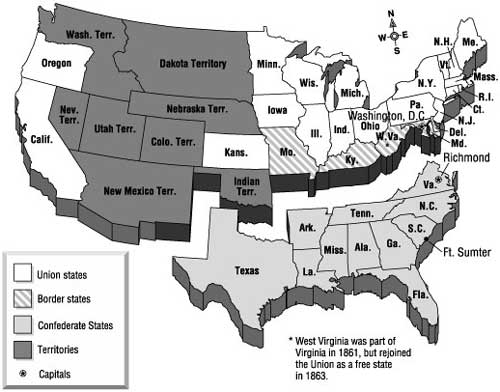

| Maryland and Civil War Border State History Map |

|

| Map depicts the hotly contested Border States as well as Southern and Northern States |

Slavery

The institution of slavery in Maryland spanned approximately two centuries,

and initially it developed along very similar lines to neighboring Virginia. The early settlements and population centers

of the Province tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay; as in Virginia,

Maryland's economy quickly became centered on the farming of tobacco for sale in Europe. The need for cheap labor to help

with the growth of tobacco, and later with the mixed farming economy that developed when tobacco prices collapsed, led to

a rapid expansion of indentured servitude and, later, forcible immigration and enslavement of Africans. The first Africans

were brought to Maryland in 1642, when 13 slaves arrived at St. Mary's City, the first English settlement in the Province.

Maryland developed into a plantation colony by the 18th century. In

1700 there were about 25,000 people and by 1750 that had grown more than 5 times to 130,000. By 1755, about 40% of Maryland's

population was black. Maryland planters also made extensive use of indentured servants and penal labor. An extensive system

of rivers facilitated the movement of produce from inland plantations to the Atlantic coast for export. Baltimore was the

second-most important port in the eighteenth-century South, after Charleston, South Carolina.

Maryland remained in the Union during the American Civil War, and so

the state was not included under the January 1, 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, which declared all slaves in Southern Confederate

states (but not those in Union Border States like Maryland) to be free. Slavery survived in Maryland until the following year,

when a constitutional convention was held which culminated in the passage of a new state constitution on November 1 1864.

Article 24 of that document outlawed the practice of slavery, and the right to vote was extended to non-white males in the

Maryland Constitution of 1867, which remains in effect today.

One feature of the new constitution was a highly restrictive oath of

allegiance which was designed to reduce the influence of Southern sympathizers, and to prevent such individuals from holding

public office of any kind. The new constitution emancipated the state's slaves (who had not been freed by President Lincoln's

Emancipation Proclamation), disenfranchised Southern sympathizers, and re-apportioned the General Assembly based upon white

inhabitants. This last provision diminished the power of the small counties where the majority of the state's large former

slave population lived.

The constitution was submitted to the people for ratification on October

13, 1864, and it was narrowly approved by a vote of 30,174 to 29,799 (50.31% to 49.69%) in a referendum widely characterized

by intimidation and fraud. This was a controversial result, given the state's Confederate ties and sympathies. Those voting

at their usual polling places were opposed to the Constitution by 29,536 to 27,541. However, the constitution secured ratification

after Maryland's soldiers' votes were included in the count. Marylanders serving in the Union Army were overwhelmingly in

favor (2,633 to 263). Maryland soldiers who were fighting for the Confederacy, and therefore could not vote, would likely

have overwhelmingly opposed it.

The new constitution, effective November 1, 1864, emancipated the state's

slaves, but this did not mean equality for them, in part because the franchise continued to be restricted to white males.

However, the abolition of slavery in Maryland did precede the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which

outlawed slavery throughout the United States, and did not come into effect until December 6, 1865. Emancipation did not immediately

bring citizenship for former slaves. The Maryland legislature refused to ratify both the 14th Amendment, which conferred citizenship

rights on former slaves, and the 15th Amendment, which gave the vote to African Americans.

| Maryland, US Expansionism, and Sectionalism Map |

|

| As the United States expanded rapidly, sectional strife intensified between the North and South |

Sentiment

Maryland, as a slave-holding Border State, was deeply divided over the

antebellum arguments over States’ Rights and the future of slavery in the Union. Culturally, geographically and economically,

Maryland found herself neither one thing nor another, a unique blend of Southern agrarianism and Northern mercantilism. In

the lead up to the American Civil War, it became clear that the state was bitterly divided in its sympathies. There was much

less appetite for secession than elsewhere in the Southern States, but Maryland was equally unsympathetic toward the potentially

abolitionist position of Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln. In the presidential election of 1860 Lincoln won just 2,294

votes out of a total of 92,421, only 2.5% of the votes cast. In seven counties, Lincoln received not a single vote.

The areas of Southern and Eastern Maryland, especially those on the

Chesapeake Bay, which had prospered on the tobacco trade and slave labor, were generally sympathetic to the South, while northern

and western areas of the state, especially Marylanders of German origin, had stronger economic ties to the North. Not all

blacks in Maryland were slaves. The 1860 Federal census indicates there were nearly as many free blacks (83,942) as slaves

(87,189) in Maryland.

However, across the state, sympathies were mixed. Many Marylanders were

simply pragmatic, recognizing that the state's long border with pro-Union Pennsylvania would be almost impossible to defend

in the event of war. Maryland businessmen feared the likely loss of trade that would be caused by war and the strong possibility

of a blockade of Baltimore's port by the Union navy. After John Brown's

raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, many citizens began forming local militias, determined to prevent a future slave uprising.

Not all those who sympathized with the rebels would abandon their homes

and join the Confederacy. Some, like physician Richard Sprigg Steuart, remained in Maryland, offered covert support for the

South, and refused to sign an oath of loyalty to the Union. Later in 1861, Baltimore resident W. W. Glenn described Steuart

as a fugitive from the authorities:

"I was spending the evening out when a footstep approached my chair

from behind and a hand was laid upon me. I turned and saw Dr. R. S. Steuart. He has been concealed for more than six months.

His neighbors are so bitter against him that he dare not go home, and he committed himself so decidedly on the 19th April

and is known to be so decided a Southerner, that it more than likely he would be thrown into a Fort. He goes about from place

to place, sometimes staying in one county, sometimes in another and then passing a few days in the city. He never shows in

the day time & is cautious who sees him at any time."

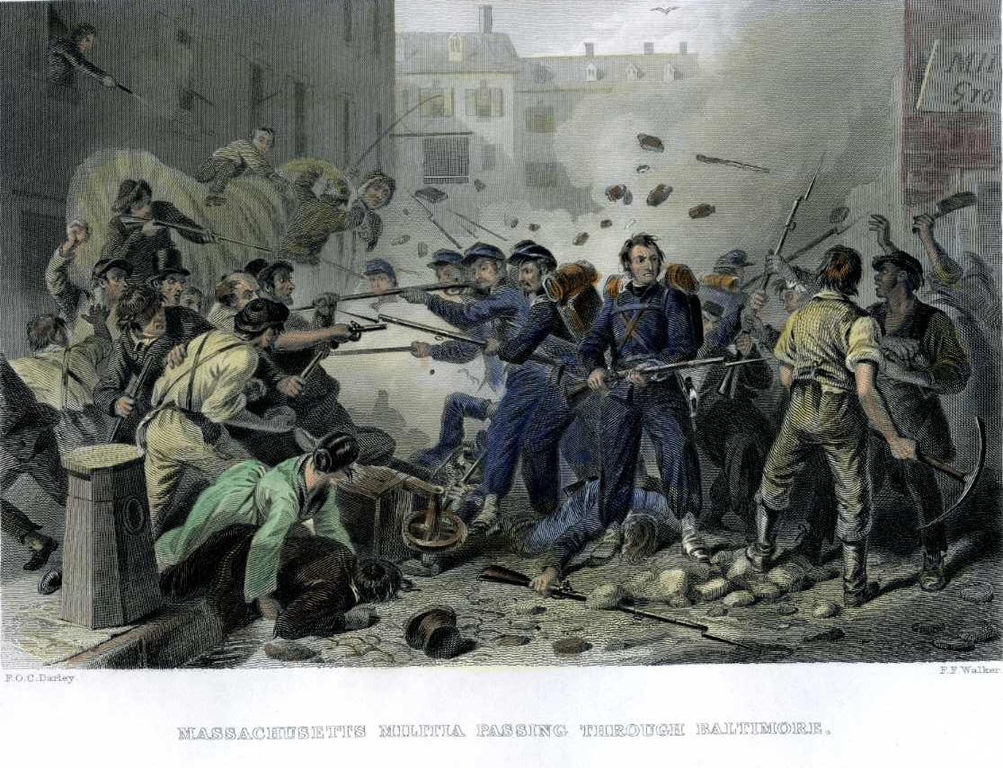

| Maryland: United We Stand, Divided We Fall! |

|

| Massachusetts Militia Passing Through Baltimore (Baltimore Riot of 1861), F.F. Walker (1861) |

Baltimore Riot of 1861

The first bloodshed of the Civil War occurred in Maryland. Anxious about

the risk of secessionists capturing Washington, D.C. (known as Washington City at the time), given that the capital was bordered

by Virginia in the south and Maryland in the north, The Federal government requested armed volunteers to suppress "unlawful

combinations" in the South. Soldiers from Pennsylvania and Massachusetts were transported by rail to Baltimore, where they

had to disembark, march through the city, and board another train to continue their journey south to Washington.

As one Massachusetts regiment was transferred between stations on April

19, a group of secessionists and Southern sympathizers attacked the train cars and blocked the route; some began throwing

cobblestones and bricks at the troops, assaulting them with "shouts and stones". Panicked by the situation, several soldiers

fired into the mob, whether "accidentally", "in a desultory manner", or "by the command of the officers" is unclear. Chaos

ensued as a giant brawl began between fleeing soldiers, the violent mob, and the Baltimore police who tried to suppress the

violence. Four soldiers and twelve civilians were killed in the riot, and dozens more were wounded.

The disorder inspired James Ryder Randall to write a poem which would

be put to music and eventually become the state song, "Maryland, My Maryland" (it remains the official state song to this

day). The song's lyrics urged Marylanders to "spurn the Northern scum" and "burst the tyrant's chain" - in other words, to

secede from the Union. Confederate States Army bands would later play the song after they crossed into Maryland territory

during the Maryland Campaign in 1862.

After the April 19 rioting, skirmishes continued in Baltimore for the

next month. Mayor George William Brown and Maryland Governor Thomas Hicks implored President Lincoln to reroute troops around

Baltimore city and through Annapolis to avoid further confrontations. In a letter to President Lincoln, Mayor Brown wrote:

"It is my solemn duty to inform you that it is not possible for more

soldiers to pass through Baltimore unless they fight their way at every step. I therefore hope and trust and most earnestly

request that no more troops be permitted or ordered by the Government to pass through the city. If they should attempt it,

the responsibility for the bloodshed will not rest upon me".

Hearing no immediate reply from Washington, on the evening of April

20 Governor Hicks and Mayor Brown formed a plan to disable the railroad bridges into the city, preventing further incursions

by Union soldiers. For a time it looked as if Maryland might join the rebels, but Lincoln moved swiftly to defuse the situation,

promising that the troops were needed purely to defend Washington, not to attack the South. President Lincoln also complied

with the request to reroute troops to Annapolis, as the political situation in Baltimore remained highly volatile. Meanwhile,

plans were being drawn up to take military control of the state.

"Two incidents reflecting on the Baltimore Riot are worthy of mention. On

June 17, 1865, a monument was unveiled in Merrimac square, Lowell, Mass., to the memory of Luther C. Ladd and Addison O. Whitney,

two soldiers of the 6th Mass., who were killed in the riot, and on this occasion Lieut.-Col. T. J. Morris, of Gov. Bradford's

staff, presented to Gov. Andrew, as the representative of Massachusetts, a fine silk flag, made by the women of Baltimore.

On the staff was a silver plate bearing the inscription: "Maryland to Massachusetts, April 19, 1865. May the Union and Friendship

of the Future obliterate the Anguish of the Past." The second incident occurred in the spring of 1898, when the 6th Mass.

— a regiment bearing the same numerical designation as the one assaulted on April 19, 1861, — marched through

Baltimore on its way to take part in the Spanish-American War. Instead of being greeted by a mob it was given an ovation by

the patriotic citizens of the Monumental City, thus fully demonstrating that the hope expressed by the inscription on the

flag-staff of 33 years before had found its fruition in a reunited country." The Union Army, vol. 2

| Maryland and Southern Secession Map |

|

| Secession of Southern States and their respective readmission to the Union dates |

Martial Law

The political situation in Maryland remained uncertain until May 13,

1861 when General Benjamin F. Butler entered Baltimore by rail with 1,000 Federal soldiers and, under cover of a thunderstorm,

quietly took possession of Federal Hill. Butler fortified his position and trained his guns upon the city, threatening its

destruction. Butler then sent a letter to the commander of Fort McHenry:

“I have taken possession of Baltimore. My troops are on

Federal Hill, which I can hold with the aid of my artillery. If I am attacked to-night, please open upon Monument Square with

your mortars.”

Butler went on to occupy Baltimore and declared martial law, in order

to prevent any further likelihood of secession. By May 21 there was no need to send further troops.

Mayor Brown, members of the city council and the police commissioner

were arrested and imprisoned at Fort McHenry. One of the militia captains was John Merryman, who was arrested and held in

defiance of a writ of habeas corpus on May 25, sparking the case of Ex parte Merryman, heard just 2 days later on May 27 and

28, in which the Chief Justice Roger B. Taney held that the arrest of Merryman was unconstitutional:

"The President, under the Constitution and laws of the United

States, cannot suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, nor authorize any military officer to do so".

Merryman created a sensation, but its immediate impact was rather limited,

as the Government and the Army simply ignored the ruling. After the occupation of the city, Union troops were garrisoned throughout

the state. Several members of the Maryland legislature were also arrested. By late summer Maryland was firmly in the hands

of Union soldiers. Arrests of Confederate sympathizers soon followed, and Steuart's brother, the militia General George H.

Steuart, fled to Charlottesville, Virginia, after which much of his family's property was confiscated by the Federal government.

Civil authority in Baltimore was swiftly withdrawn from all those who had not been steadfastly in favor of the Federal government's

emergency measures.

| Maryland Civil War Battlefield Map |

|

| Map of Principal Civil War Battles in Maryland |

Secession

Although Maryland remained in the Union, it was accomplished by

the strong hand and strong-arm tactics of President Abraham Lincoln.

The weeks following the Baltimore Riot of 1861 were tense as troop lines

were reestablished. On April 27, President Lincoln authorized the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus in Maryland. Lincoln

also ordered the military to arrest several Confederate sympathizers and hold them as political prisoners. John Merryman was

among those incarcerated at Fort McHenry. When Merryman appealed for his release, Chief Justice Roger Taney, in ex parte Merryman,

ruled that the Constitution permitted only Congress to suspend the writ. This debate on civil liberties only served to further

galvanize citizens of Maryland against Union occupation.

Despite considerable popular support for the cause of the Confederate

States of America, Maryland would not secede during the Civil War. However, a number of leading citizens, including physician

and slaveholder Richard Sprigg Steuart, placed considerable pressure on Governor Hicks to summon the state Legislature to

vote on secession, following Hicks to Annapolis with a number of fellow citizens:

"to insist on his [Hicks] issuing his proclamation for the Legislature

to convene, believing that this body (and not himself and his party) should decide the fate of our state"...if the Governor

and his party continued to refuse this demand that it would be necessary to depose him".

Responding to pressure, on April 22 Governor Hicks finally announced

that the state legislature would meet in a special session in Frederick, a strongly pro-Union town. The Maryland General Assembly

convened in Frederick and unanimously adopted a measure stating that they would not commit the state to secession, explaining

that they had "no authority to take such action" whatever their own personal feelings might have been. On April 29, the Legislature

voted 53–13 against secession. See also Maryland in the American Civil War (1861-1865).

Civil War

According to the 1860 U.S. census, Maryland had a free population of

599,860 and an additional slave population of 87,189. During the American Civil War (1861-1865) as many as 30,000 Marylanders

traveled south to fight for the Confederacy, while approximately 65,000* Maryland men,

including nearly 9,000 colored troops, served in all branches of the Union military. Marylanders in the Union Army served

in 20 regiments and 1 independent company of infantry, 4 regiments and 4 companies of cavalry, 6 batteries of light artillery,

and 6 regiments of colored infantry.

During the conflict, Marylanders fought

in practically every major theater, and the state was host to some of the deadliest fighting. By war's end, Maryland troops

suffered more than 3,000 in killed and several thousands more in wounded. Casualties at the Battle of Antietam, Maryland,

were greater than 23,000, and it was the bloodiest single-day battle in American history and the 8th

deadliest and bloodiest engagement of the entire war. Although Antietam was Lee's first invasion

of the North, he made a second and final attempt into Union territory at Gettysburg less than one year later.

Prominent Maryland leaders and officers during the Civil War included

Governor Thomas H. Hicks who, despite his early sympathies for the South, helped prevent the state from seceding, and General

George H. Steuart, who was a noted brigade commander under General Robert E. Lee. The Brothers' War, another name for

the American Civil War, and divided loyalties may be seen in other Marylanders: Union Brevet Brig. Gen. James

Monroe Deems was an American composer and music educator; Confederate Brig. Gen. James Jay Archer was the first brigadier

prisoner-of-war from Lee's Army of Northern Virginia; Union NCO Christian Fleetwood was an African-American soldier who was

awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor; Union Brig. Gen. Henry Moses Judah was a Jewish soldier who assisted in thwarting

Morgan's Raid in 1863 but led a disastrous attack during the Battle of Resaca; Union Bvt. Maj. Gen. John Reese Kenly commanded

a division in the Army of the Potomac; Union Rear Admiral Samuel Phillips Lee served in many capacities before commanding

the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron; Confederate Rear Admiral Raphael Semmes was captain of the commerce raider CSS Alabama

— which took 65 prizes; Confederate Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman was selected by the Rebel government to build two forts

to defend the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers, and he was killed at the Battle of Champion Hill during the defense of Vicksburg;

and Confederate Maj. Gen. Isaac Ridgeway Trimble was wounded and captured during Pickett's ill-fated charge and spent the

remainder of the conflict as a POW.

Many Marylanders sympathetic to

the South easily crossed the Potomac River into secessionist Virginia in order to join and fight for the Confederacy. During

the early summer of 1861, several thousand Marylanders crossed the Potomac River to join the Confederate Army. Most

of the men enlisted in regiments from Virginia or the Carolinas, but six companies of Marylanders formed at Harpers Ferry

into the Maryland Battalion. Among them were members of the former volunteer militia unit, the Maryland Guard Battalion, initially

formed in Baltimore in 1859.

Maryland Exiles, including Arnold Elzey and brigadier general George

H. Steuart, would organize a "Maryland Line" in the Army of Northern Virginia which eventually consisted of one infantry regiment,

one infantry battalion, two cavalry battalions and four battalions of artillery. Most of these volunteers tended to hail from

south and eastern counties of the state, while northern and western Maryland furnished more volunteers for the Union armies.

Captain Bradley T. Johnson refused the offer of the Virginians to join

a Virginia Regiment, insisting that Maryland should be represented independently in the Confederate army. It was agreed that

Arnold Elzey, a seasoned career officer from Maryland, would command the 1st Maryland Regiment. His executive officer was

the Marylander George H. Steuart, who would later be known as "Maryland Steuart" to distinguish him from his more famous cavalry

colleague JEB Stuart.

During hostilities, Maryland, a slave state, was one of the Border States straddling the South and North. Because of its strategic location, bordering

the capital city of Washington D.C., and the strong desire of the opposing factions within the state to sway public opinion

toward their respective causes, Maryland would play an important role in the conflict. The

State of Maryland would experience from raids, operations, to campaigns, with its most notable Civil War battles fought at

Antietam (aka Sharpsburg); Boonsboro; Folck's Mill; Hancock; Monocacy; South Mountain; Williamsport; and Fort Stevens.

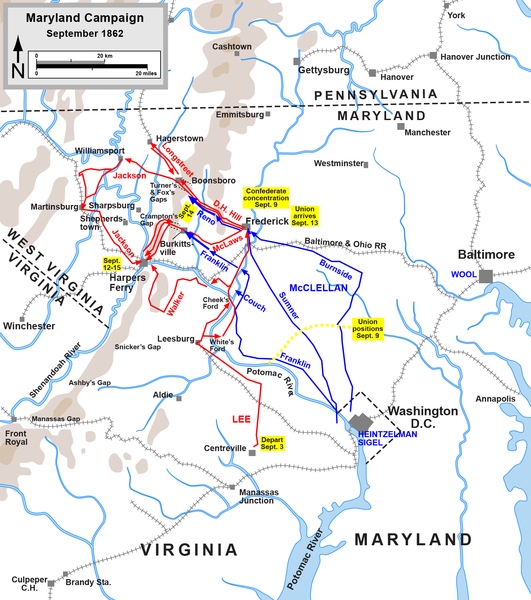

| Maryland in the Civil War Map |

|

| Maryland Campaign Map |

The first fatalities of the war happened

during the Baltimore Riot of April 1861, and the single bloodiest day of combat in American military history occurred

near Sharpsburg, Maryland, at the Battle of Antietam, on 17 September 1862. Antietam, though tactically a draw, was strategic

Union victory that gave President Abraham Lincoln the opportunity to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared slaves

in the Confederacy (but not those in Border States like Maryland) to be free.

Gen. Robert E. Lee's first invasion of the North, September 4–20,

1862, known as the Antietam or Maryland Campaign, was repulsed by the Army of the Potomac under Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan,

who moved to intercept Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia and eventually attacked it near Sharpsburg, Maryland. The resulting

Battle of Antietam was the bloodiest single-day battle in American history and is widely considered one of the major turning

points of the war.

Following his victory in the Northern Virginia Campaign, Lee moved north

with nearly 55,000 men through the Shenandoah Valley starting on September 4, 1862. His objective was to resupply his

army outside of the war-torn Virginia theater and to damage Northern morale in anticipation of the November elections. He

undertook the risky maneuver of splitting his army so that he could continue north into Maryland while simultaneously capturing

the Federal garrison and arsenal at Harpers Ferry. McClellan accidentally found a copy of Lee's orders to his subordinate

commanders and planned to isolate and defeat the separated portions of Lee's army.

While Maj. Gen. Stonewall Jackson surrounded, bombarded, and captured

Harpers Ferry (September 12–15), McClellan's army of 87,000 men attempted to move

quickly through the South Mountain passes that separated him from Lee. The Battle of South Mountain on September 14 delayed

McClellan's advance and allowed Lee sufficient time to concentrate most of his army at Sharpsburg. The Battle of Antietam (or Sharpsburg) on September 17 was the bloodiest day in American military

history with more than 23,000 casualties. Lee, outnumbered two to one, moved his defensive forces to parry each offensive

blow, but McClellan never deployed all of the reserves of his army to capitalize on localized successes and destroy the Confederates.

On September 18, Lee ordered a withdrawal across the Potomac and on September 19–20, fights by Lee's rear guard at Shepherdstown

ended the campaign.

Although Antietam was a tactical draw, Lee's Maryland Campaign failed

to achieve its objectives. President Abraham Lincoln used this Union victory as the justification for announcing his Emancipation

Proclamation, which effectively ended any threat of European support for the Confederacy.

Early in June 1863, the Confederate army under Gen. Lee began moving down

the Shenandoah Valley and it soon became evident that another invasion of Maryland was intended. On the 15th President Lincoln

issued his proclamation calling for 100,000 men, to be immediately mustered into the service of the United States for six

months, unless sooner discharged. Of this levy Maryland was to raise 10,000 men.

Accordingly on the 16th Gov. Bradford published an appeal to the people

of the state to furnish the 10,000 by voluntary enlistments. The Baltimore city council, in extra session, appropriated $400,000

to be paid as bounties to those enlisting before June 26, $50 to be paid at the time of enlistment and $10 a month thereafter

for five months. Under this stimulus all the uniformed military organizations of the city offered their services for the six

months under the call, and other portions of the state were equally prompt in furnishing their proportion of the levy. Lee's

invasion ended disastrously for the Confederates in the battle of Gettysburg, and at the expiration of the term of enlistment

these emergency troops, as they were called, were mustered out.

The Gettysburg Campaign was a series of battles fought in June

and July 1863. After Gen. Lee’s victory in the Battle of Chancellorsville, Gen. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia moved north for offensive operations

in Maryland and Pennsylvania. The Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker and then (from June 28)

by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, pursued Lee, defeated him at the Battle of Gettysburg, but allowed him to retreat to Virginia.

Lee's army slipped away from Federal contact at Fredericksburg, Virginia,

on June 3, 1863. While they paused at Culpeper, the largest predominantly cavalry battle of the war was fought at Brandy Station

on June 9. The Confederates crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains and moved north through the Shenandoah Valley, capturing the

Union garrison at Winchester, Virginia, in the Second Battle of Winchester, June 13–15. Crossing the Potomac River,

Lee's Second Corps advanced through Maryland and Pennsylvania, reaching the Susquehanna River and threatening the state capital

of Harrisburg. However, the Army of the Potomac was in pursuit and had reached Frederick, Maryland, before Lee realized his

opponent had crossed the Potomac. Lee moved swiftly to concentrate his army around the crossroads town of Gettysburg.

The Battle of Gettysburg was the largest and deadliest of the war. Starting

as a chance meeting engagement on July 1, the Confederates were initially successful in driving Union cavalry and two infantry

corps from their defensive positions, through the town, and onto Cemetery Hill. On July 2, with most of both armies now present,

Lee launched fierce assaults on both flanks of the Union defensive line, which were repulsed with heavy losses on both sides.

On July 3, Lee focused his attention on the Union center. The defeat of his massive infantry assault, Pickett's Charge, caused

Lee to order a retreat that began the evening of July 4.

The Confederate retreat to Virginia was plagued by bad weather, difficult

roads, and numerous skirmishes with Union cavalry. However, Meade's army did not maneuver aggressively enough to prevent the

Army of Northern Virginia from crossing the Potomac to safety on the night of July 13–14.

At the beginning of 1864, Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to lieutenant general

and given command of all Union armies. He chose to make his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac, although Maj. Gen.

George G. Meade remained the actual commander of that army. He left Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman in command of most

of the western armies. Grant understood the concept of total war and believed, along with Sherman and President Abraham Lincoln,

that only the utter defeat of Confederate forces and their economic base would bring an end to the war. Therefore, scorched

earth tactics would be required in some important theaters. He devised a coordinated strategy that would strike at the heart

of the Confederacy from multiple directions: Grant, Meade, and Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler against Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern

Virginia near Richmond; Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel to invade the Shenandoah Valley and destroy Lee's supply lines; Sherman to invade

Georgia and capture Atlanta; Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks to capture Mobile, Alabama.

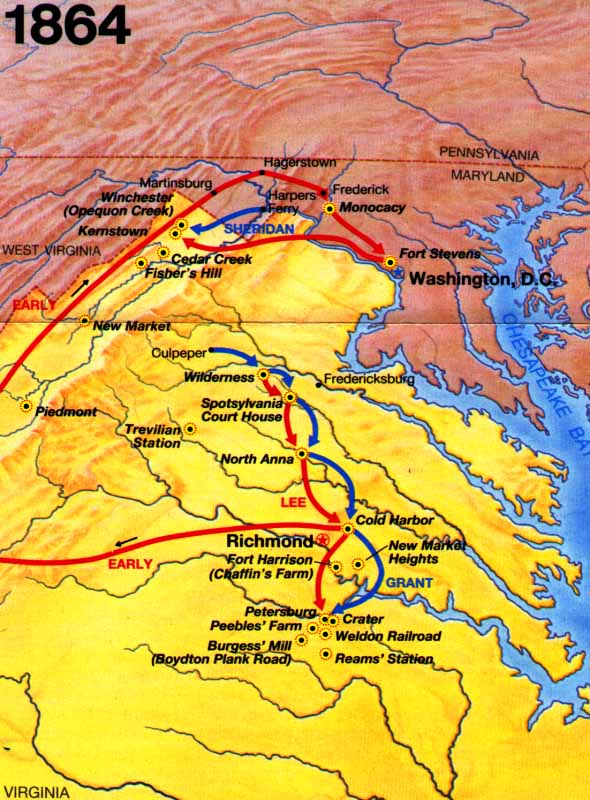

| 1864 Maryland Civil War Map |

|

| Gen. Early enters Maryland! |

Robert E. Lee was concerned about the Union advance in the Valley during 1864,

which threatened critical railroad lines and provisions for the Virginia-based Confederate forces. As a result, Lee sent Jubal

Early's corps, the Army of the Valley (independent command of the Army of Northern Virginia's Second Corps, renaming it the

Army of the Valley), to sweep Union forces from the Valley and, if possible, to menace Washington, D.C.,

hoping to compel Grant to dilute his forces against Lee around Petersburg,

Virginia. Early was operating in the shadow of Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson,

whose 1862 Valley Campaign against superior forces was etched in Confederate history. Early had a good start as he proceeded

down the Valley without opposition, bypassed Harpers Ferry, crossed the Potomac River, and advanced into Maryland. Grant dispatched a corps under Horatio G. Wright and other troops under George Crook to reinforce

Washington and pursue Early.

The Confederacy's main objective of the entire series of battles was to pull,

draw or lure Grant's army and resources away from Lee, who was pinned down in the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign (aka Siege of Petersburg), and consequently relieve Lee of the overwhelming Union resources that confronted

him. Although the hotly contested Shenandoah Valley Campaigns resulted in 33,000 Union and Confederate casualties, it is perhaps the least

studied and talked about of all the Civil War campaigns.

Originally organized as the Second Corps in Lee's army, Early's Army of the

Valley (officially the Army of the Valley District) numbered approximately 14,000 soldiers. The infantry, totaling near 9,000,

was organized into two corps, each consisting of two divisions. The First Corps was commanded by Robert E. Rodes, a Virginia

Military Institute graduate and one of the highest-ranking Confederate officers not to have attended the U.S. Military Academy

at West Point, New York. The Second Corps, meanwhile, was led by John C. Breckinridge (cousin to Mary Todd Lincoln), the former

U.S. vice president under James Buchanan and a Democratic candidate for president in 1860 (ran against Lincoln). The North

Carolinian Robert Ransom commanded roughly 4,000 cavalrymen, organized into four brigades. Approximately sixteen artillery

batteries supplemented the army.

The Shenandoah Valley held considerable strategic and logistical promise that

attracted the attention of both Union and Confederate forces. The 1864 Valley Campaign far exceeded Confederate general Thomas

J. "Stonewall" Jackson's famed 1862 Valley Campaign in scope and impact. Early's Army of the Valley engaged in systematic

marching maneuvers up and down the Valley, engaged Union forces in numerous battles, offered resistance to Union general Philip

H. Sheridan's hard-war policies, invaded Maryland and Pennsylvania twice, and also ransomed and burned Northern cities in

hard-war tactics of its own.

Lt. Gen. Jubal Early's independent command during the Shenandoah Valley Campaigns in the summer and autumn of 1864 was the last Confederate unit to invade Northern

territory, reaching the outskirts of Washington, D.C. (The Army, however, became defunct after its decisive defeat at the Battle of

Waynesboro, Virginia, on March 2, 1865.)

The Confederate's invasion of Maryland arrived in the early part of July,

1864, when the Southern forces under Gen. Early suddenly and unexpectedly entered the Cumberland valley. The people of Hagerstown

were forced to raise $20,000 to prevent the destruction of the city, and a demand was made upon the merchants to furnish from

their stocks of goods 1,500 suits of clothes, 1,500 hats, 1,500 pairs of shoes, 1,500 shirts, 1,900 pairs of drawers and 1,500

pairs of socks within four hours. There were not enough articles in the city of the kind described to comply with the demand,

but all that could be found were appropriated, after which Gen. McCausland gave the city authorities a written assurance against

any further tribute being levied against the town or its citizens. From Hagerstown Early moved on Frederick City, which was

evacuated by the Union troops, and a demand was made for $200,000, in default of which payment the city would be burned. Mayor

Cole called together the officials remaining in the city and after a short consultation decided to submit to the terms and

ransom the city. The money was accordingly paid in United States currency, Confederate money and bank notes being refused,

and the Confederate soldiers visited the stores and "took what they wanted," sometimes offering Confederate currency in payment,

but more frequently without either offer of compensation or apology. Early's advance was checked by Gen. Wallace at Monocacy

on the 9th and he made a precipitate retreat back to Virginia.

The Battle of Monocacy (aka Battle that Saved Washington) was fought on Maryland soil on July 9, 1864,

and was a tactical victory for the Confederate army but a strategic defeat, as the delay inflicted on the Southerners cost

General Jubal Early his chance to capture the Federal capital of Washington, D.C. (See also Battle of Fort Stevens: The Civil War Battle

of Washington.)

During March 1865, Gen. Early's army was captured by Gen. Sheridan at Waynesboro,

thus eliminating the remaining threat in the valley. After nearly ten months of exhaustive

siege warfare, during the Richmond-Petersburg Siege, Lee's army was weakened by desertion, disease, and shortage of supplies,

and, while Grant commanded an army of 125,000 men, the Confederate general was in command of 50,000 troops. Lee, moreover,

knew that an additional 50,000 men under Sheridan would be returning soon from the Shenandoah

Valley and that Sherman, as of April 1, 1865, commanded a massive army of 88,948

troops and too was rapidly approaching Richmond. Lee, now pressed on every front, surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9, 1865, and ended the bloodiest conflict in the history

of the nation. See also Maryland Civil War History and Maryland in the American Civil War (1861-1865).

| Fort McHenry, Baltimore, Maryland |

|

| Union soldiers manned and aimed these cannon toward downtown Baltimore |

Fort McHenry

Fort McHenry, in Baltimore,

Maryland, is a coastal star-shaped fort best known for its role in the War of 1812, when it successfully defended Baltimore

Harbor from an attack by the British navy in Chesapeake Bay during September 13–14, 1814. It was during the bombardment

of the fort that Francis Scott Key was inspired to write "The Star-Spangled Banner," the poem that would eventually be set

to the tune of "To Anacreon in Heaven" and become the national anthem of the United States. During the Civil War, Key’s

grandson, Francis Key Howard, was imprisoned at McHenry because, according to President Lincoln’s policy, he was deemed

a Southern sympathizer along with 2,000 political prisoners, including 28 newspapermen, 31 members of the Maryland General

Assembly, and the mayor of Baltimore. Freedom of Speech and Due Process were ignored.

During the Civil War, Union

troops, stationed at Fort McHenry, turned the fort’s guns toward Baltimore to ensure that Baltimore, as well as Maryland,

would remain in the Union.

During the conflict, Fort

McHenry served as a Union transfer prison camp for Southern sympathizers and confederate prisoners-of-war. Usually, prisoners

were confined at the fort for short periods of time before being transferred to such larger prisons as Point Lookout, Fort

Delaware or Johnson's Island.

In May, 1861, Union officials

began arresting Marylanders suspected of being Confederate sympathizers. Many never were charged with a crime and never received

trials. “Lincoln’s justification for Imprisonment ranged from raising the Confederate flag at one’s

home to speaking to a Southerner to riding your horse across the border into Virginia.” Many sympathizers were released

after pledging not to "render any aid or comfort to the enemies of the Union," or by taking an oath of allegiance.

The imprisoned included

newly-elected Baltimore Mayor George William Brown, the city council, and the new police commissioner, George P. Kane, and

members of the Maryland General Assembly along with several newspaper editors and owners. Among the most prominent civilians

detained at the fort were the marshal of the Baltimore City Police force and the board of police commissioners, the mayor

of Baltimore, a former governor of Maryland, members of the House of Delegates from Baltimore City and County, the congressman

from the 4th Congressional District, a state senator, newspaper editors, including the grandson of Francis Scott Key, ministers,

doctors, judges and lawyers. Prisoners-of-war included privates, officers, chaplains and surgeons.

A drama beginning the famous

Supreme Court case involving the night arrest in Baltimore County and imprisonment here of John Merryman and the upholding

of his demand for a writ of habeas corpus for release by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney occurred at the gates between Court

and Federal marshals and the commander of Union troops occupying the Fort under orders from President Abraham Lincoln in 1861.

Life at Fort McHenry was

very difficult. Each prisoner was given one blanket, but was denied bedding, chairs, stools, wash basins and eating utensils.

They used a tin cup, pocket knife, hardtack for a plate, and forks and spoons whittled from bits of wood. Prisoners received

three meals each day: breakfast, consisting of coffee and hardtack; a second meal of bean soup and hardtack; and a main meal

of coffee, 1/2 pound of salt pork or pickled beef and hardtack. Occasionally, the meat would be rancid and the hardtack moldy.

The prisoners who could afford to do so, bought fresh fruits, vegetables and comfort items from sutlers. Also, sympathizers

from Baltimore sent large quantities of food, clothing, blankets and money. The prisoners spent their time engaged in a number of activities. They formed literary societies and debating teams.

Many made trinkets which they traded for extra rations. There were daily ball games and rat hunts. Each evening, the prisoners

staged a show.

At times, the inmate population

swelled to numbers that severely strained the prison facilities. In February, 1862, there were only 126 prisoners at Fort

McHenry. Early in 1863, the number of prisoners totaled 800. However, in July, 1863, following the battle of Gettysburg, there

were 6,957 prisoners. After the large Gettysburg influx was dispersed, the monthly total ranged between 250 and 350 prisoners.

During the last months of the war, the number dwindled sharply; and in September, 1865, there were only 4 prisoners at the

fort. At the end of 1865, only a small detachment of Union troops remained to handle routine maintenance.

In contrast to the high

death tolls at other prisons, the death toll at Fort McHenry was only 15. At least three men were executed at the fort. These

included a Union soldier hanged for the murder of an officer, another, shot after having been found guilty of desertion and

the attempted murder of several civilians, and a confederate sympathizer found guilty of murdering two civilians while practicing

guerrilla warfare. Because of its role as a prison camp during the Civil War, Fort McHenry became known as the "Baltimore

Bastille."

Historical Significance

Among the many historic

events which occurred during the Civil War, one stands out in special relation to Fort McHenry. It was an event which tested

the powers of the President against the limits of power of the Presidency written into the Constitution. At the beginning

of the war Lincoln stretched his powers to the edge. In the eyes of many, he went over that edge and violated constitutional

law.

The war began in 1861,

and until Congress could convene in July the President was forced to make decisions without the advice and consent of Congress.

One of these was deciding on measures to take to insure Maryland did not secede and join the Confederacy.

Maryland was rife with

secessionists. Many prominent citizens in the state openly voiced their hatred for Lincoln and the U.S. Army. Many supporters

rallied to their call of "Secession" in Baltimore. Obviously, Lincoln was desperate to keep Maryland in the Union for it was

through Baltimore that vital rail and telegraph lines passed from the west and north before proceeding to Washington. So determined

was the President to preserve the North’s tenuous hold on Maryland, that he sanctioned extreme measures against the

state's secessionists.

A Writ of Habeas Corpus

On April 27th Lincoln startled

the country by suspending the Constitutional privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus along the military lines from Washington

to Philadelphia. Habeas Corpus is a personal right that goes back to English common law, predating our own Constitution. In

short, the Writ says that a person being arrested must be charged with a specific crime or he/she must be released. It is

a safeguard against unlawful seizures and violation of due process. By suspending the Writ, Lincoln gave de facto powers to

the U.S. Army to arrest, and hold indefinitely, anyone it pleased. Lincoln's aim was to silence any opposition that might

catapult Maryland into secession and to preserve national safety.

John Merryman

On May 25, 1861, U.S. Soldiers

arrested John Merryman at his home "Hayfields" in Cockeysville, Maryland. He was a lieutenant in the Maryland State Militia

who had (under orders from the Governor) burned rail bridges north of Baltimore to prevent the passage of northern troops

through the city. The army confined Merryman at Fort McHenry, and he was held without charges and denied legal counsel.

Chief Justice Roger B.

Taney

Hearing of Merryman's plight,

Chief Justice Taney intervened. He issued a Writ of Habeas Corpus to Fort McHenry's commanding officer, Major George Cadwalader.

However, citing military orders from the President, Cadwalader had the Writ refused at the Forts outer gate. Taney's written

opinion, known afterwards as "Ex Parte Merryman," stated that only Congress has the power to suspend the Writ, and then, only

in cases of extreme emergency. He admonished the President for overstepping his Constitutional limits; as he had no right

to suspend the Writ.

The President's Response

Lincoln read Taney's opinion,

but decided not to honor it. He felt the state of affairs warranted emergency action, and since Congress was not in session,

he had to act on its behalf. In response to Taney's opinion, Lincoln wrote, "Are all the laws but one to go unexecuted and

the government itself go to pieces lest that one be violated." As the war progressed, the arrests continued, and Lincoln suspended

the Writ as far north as Maine. On March 3, 1863, Congress authorized the President to suspend the Writ.

In The Minds of the People

In the minds of Lincoln's

supporters, the president's actions were necessary to preserve the Union and essential to the survival of the United States.

The Southern leaders, however, condemned Lincoln, calling him a dictator, a despot, and also a man who would stop at

nothing to gain total power. Were Lincoln's actions lawful? Was

the conduct necessary? Was Lincoln a tyrant or dictator, or were his actions justified in order to hold together the country

in its most perilous hour? Think about it. You decide.

| Maryland Civil War Battlefield Map |

|

| High Resolution Map of Maryland |

| Maryland and the Civil War |

|

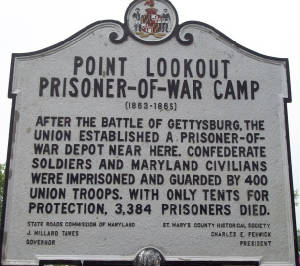

| Point Lookout Prison Historical Marker |

Point Lookout Prison

Point Lookout, aka Point Lookout Prison Camp, was the largest Union

Prisoner-of-War camp in the North. It was located in Ridge, Maryland, approximately 80 miles south of Washington, D.C., at

the mouth of the Potomac River. During the Civil War, the Union Army established a hospital on the site after General George

McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign failed to capture Richmond. Following the Battle of Gettysburg, the Union desperately

needed a repository for Confederate soldiers in the region; as a consequence Point Lookout was transformed into a prison.

As in many Union prisons, the inmate population at Point Lookout ballooned

as the war progressed. Between 1863 and 1865, more than 50,000 Confederate prisoners passed through the gates of Point Lookout.

Many prisoners briefly stayed in Point Lookout before transferring to other prisons farther north. At various points over

this period, the total population of Point Lookout reached 20,000 or more, double the intended capacity. Approximately 4,000

Confederates died at the site. Many of the inmates lived in tents instead of barracks, which contributed to the large number

of deaths by exposure.

Confederate remains at Point Lookout are interred in a common grave.

Originally, the soldiers were buried in two cemeteries near the prison camp. However, in 1870 the state of Maryland removed

the remains to a more favorable site one-mile inland. After the transfer, the individual graves could not be identified; as

a result the remains were buried in a common grave. In 1910, Maryland asked the Federal government to assume care of the burial

site and, toward that end, passed an act relinquishing all right, title, and interest in the cemetery.

Aftermath

Before the war, Maryland's economy was divided between slave plantations

in the South, small farms in the North, and manufacturing industry in Baltimore. Manufacturing became dominant after the war.

The end of the war would bring the abolition of slavery in Maryland,

with a new constitution voted in 1864 by a wafer-thin majority. Such was the disgust of Marylander John Wilkes Booth at this

outcome that in April 1865 he assassinated President Lincoln, crying "I have done it, the South is avenged!".

Since Maryland had remained in the Union during the Civil War, the state

did not undergo Reconstruction like the states of the former Confederacy. However, as a former "slave state", many Maryland

residents struggled to maintain white supremacy over freedmen and formerly free blacks, and racial tensions rose. There were

deep divisions in the state between those who fought for the North and those who fought for the South, which were also difficult

to reconcile.

The whites in the Democratic Party rapidly regained power in the state

and replaced Republicans who had ruled during the war. Support for the Constitution of 1864 ended, and Democrats replaced

it with the Maryland Constitution of 1867. That document, which is still in effect today, resembled the 1851 constitution

more than its immediate predecessor and was approved by 54.1% of the state's population. Although the reapportionment of the

legislature based on population, not counties, gave greater power to freedmen (as well as to urban areas), the new constitution

deprived African Americans of some of the protections of the 1864 document.

Over the next several decades, the African-American population

struggled in a discriminatory environment. In 1910 the legislature proposed the Digges Amendment to the state constitution.

It would have used property requirements to effectively disfranchise many African Americans as well as many poor whites (including

new immigrants), a technique used by other Southern states of that period, beginning with Mississippi in 1890. The Maryland

General Assembly passed the bill, which Governor Austin Lane Crothers supported. Before the measure went to popular vote,

a bill was proposed that would have effectively passed the requirements of the Digges Amendment into law. Due to wide public

opposition, that measure failed, and the amendment was also rejected by the voters of Maryland. This was the most notable

rejection nationally of a black-disfranchising amendment. Similar measures had earlier been proposed, but also failed to pass (the Poe Amendment in 1905 and the Straus Amendment in 1909).

The businessmen Johns Hopkins, Enoch Pratt, George Peabody, and Henry

Walters were philanthropists of 19th-century Baltimore; they founded notable educational, health care, and cultural institutions

in that city, which bear their names, including a university, library, music school and art museum.

*65,000 is an estimate since, depending on the source, totals vary

slightly. Estimates for Maryland, furthermore, range from 60,000 to 70,000 Union troops, which would include

the following: Volunteers, Militia, Marylanders serving in U.S. units (referred to as "regulars"), Navy, Marines, and nearly

9,000 colored troops. The Union Army, vol 2, p. 270, states that "From

the beginning to the close of the war Maryland furnished twenty regiments and one independent company of infantry; four regiments,

one battalion and one independent company of cavalry; and six light batteries — a total of 50,316 white troops —

and six regiments of colored infantry, numbering 8,718 men. In addition to these volunteers the state furnished her due proportion

to the regular army of the United States and 5,636 men to the navy and marine corps."

See also

Sources: National Park Service; National Archives; Library of Congress;

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; The Union Army (1908); US Census Bureau; Veterans Affairs; Maryland

State Archives; Baltimore City Archives; Maryland Historical Society; A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion by Frederick

L. Dyer (Morningside Books, 1978); Phisterer, Frederick. Statistical record of the armies of the United States (1883); Fox, William F. Regimental Losses in the American Civil War (1889); Hardesty,

Jesse. Killed and died of wounds in the Union army during the Civil War (1915) Wright-Eley Co.; Baltimore

During the Civil War by Daniel C. Toomey and Scott S. Sheads (Toomey Press; (1997) Civil War Burials in Baltimore: Loudon

Park Cemetery by Anna M. Watring (Baltimore, 1996); Selected Records of the War Department Relating to Confederate Prisoners

of War, 1861-1865; Fort McHenry Military Prison (National Archives, M-598, Roll 96)ƒ The Union: A Guide to Federal Archives

Relating to the Civil War By K. Munden and H. Beers (NARA, 1986); The Confederacy : A Guide to the Archives of the Government

of the Confederates States of America By H. Beers, (NARA, 1986); Military Service Records: A Select Catalog of National Archives

Microfilm publications (National Archives, 1985); Andrews, Matthew Page,

History of Maryland, Doubleday, New York (1929); Arnett, Robert J., et al., Maryland: A New Guide to the Old Line State

The Johns Hopkins University Press (1999); Brugger, Robert J. (1988). Maryland, A Middle Temperament: 1634-1980. Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5465-2; Chappelle, Susan Ellery Green; et al. (1986). Maryland: A History

of its People. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-3005-2; Clayton Colman Hall, ed. Narratives of Early

Maryland, 1633–1684 (1910); Curry, Denis, C., "Native Maryland, 9000 B.C.-1600 A.D." (2001); Davis, David Brion, Inhuman

Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World; David Hein, editor. Religion and Politics in Maryland on the Eve of

the Civil War: The Letters of W. Wilkins Davis. 1988; revised ed., Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2009; Denton, Lawrence

M. (1995). A Southern Star for Maryland. Baltimore: Publishing Concepts. ISBN 0-9635159-3-4; Freehling, William H., The Road

to Disunion: Volume I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776-1854; Gallagher, Gary W., Antietam: Essays on the 1862 Maryland Campaign,

Kent State University Press (31 Dec 1992); Gillipsie, James M., Andersonvilles Of The North: The Myths and Realities

of Northern Treatment of Civil War Confederate Prisoners, University of North Texas Press (2011); Goldsborough, W. W.,

The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army, Guggenheimer Weil & Co (1900), ISBN 0-913419-00-1; Hein, David (editor),.

Religion and Politics in Maryland on the Eve of the Civil War: The Letters of W. Wilkins Davis. 1988. Rev. ed., Eugene, OR:

Wipf & Stock, 2009; Maryland State Archives (16 Sept. 2004). Historical Chronology; Mitchell, Charles W., Maryland

Voices of the Civil War; Scharf, J. Thomas (1967 (reissue of 1879 ed.)). History of Maryland From the Earliest Period

to the Present Day. 3. Hatboro, PA: Tradition Press; Scharf, J. Thomas, History of Western Maryland: Being a History

of Frederick, Montgomery, Carroll, Washington, Allegany, and Garrett Counties. (1882); Tagg, Larry, The Generals of Gettysburg,

Savas Publishing (1998), ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

Return to American Civil War Homepage

|

|

|