|

|

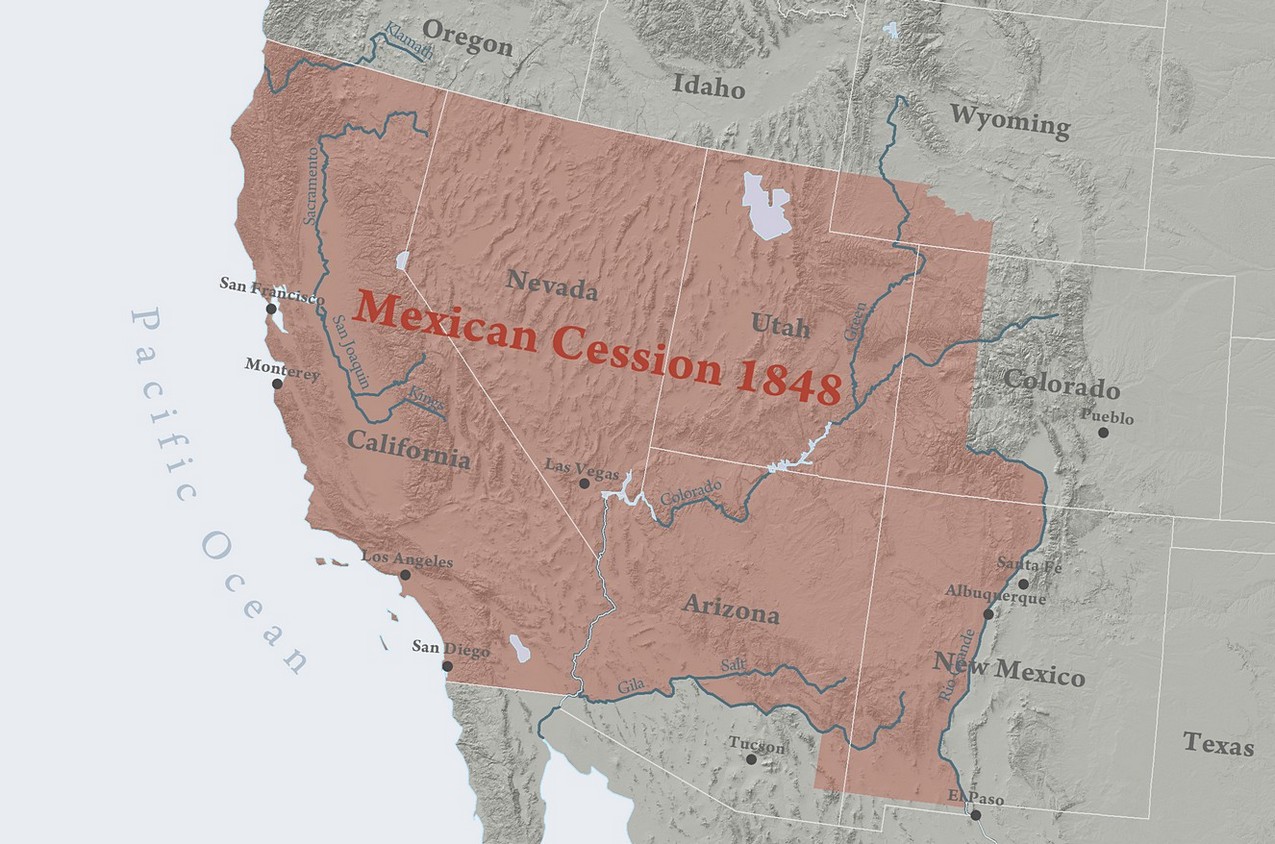

Mexican Cession and Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Mexican Cession History Lesson

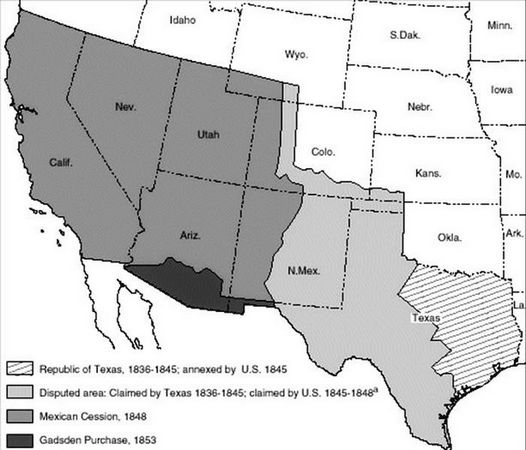

| Official Mexican Cession Map |

|

| Mexican Cession Map, aka Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo |

Introduction

The Mexican Cession, officially the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ended the Mexican-American War (1846–48) and was signed on February 2, 1848, at Guadalupe Hidalgo, a city to which the Mexican government had fled.

The major concession from Mexico in the Cession was its exchange of fifty five percent of its territory to the United States

for a sum of fifteen million dollars. As a result of the Treaty, including the official recognition of the State of Texas,

the United States had enlarged its territorial boundaries by more than sixty percent and it stretched its borders from sea

to shining sea. In only four years, from its annexation and statehood of Texas in 1845 to the lands gained by the Mexican

Cession in 1848, the United States had literally become a global power. The country also enjoyed its position as a nation

bordered by a conquered foe to its south, a sparsely populated Canada to its north, and the Pacific and Atlantic oceans

on its west and east coasts, respectively.

Once the Treaty was signed, the United States owned more

than one-half of Mexico and it boundaries now spanned from the Atlantic to Pacific oceans. From the signing of the Declaration

of Independence on July 4, 1776, the fledgling 13 Colonies had expanded westward and from sea to shining sea in merely 72

years, and by doing so it had henceforth removed the presence of the global powers of England, Spain, and France.

The cost of the Mexican Cession was

immense for both nations, however. Following the humiliating defeat Mexico plunged into civil war and with its loss of vast

territory to its north, the nation was bankrupt and its economy and infrastructure would be stymied for nearly a century.

Just weeks after the Mexican Cession was signed, gold was discovered in California

(California was known for a long time as El Dorado, which means “the land of gold” in Spanish), leading to the

largest gold rush in the history of the United States. But unfortunately for Mexico, El Dorado was not part of Mexico anymore.

Americans known as 49ers would enjoy one of the greatest spoils of war in world history. (Now you

know the origin of the namesake San Francisco 49ers.)

The United States and its

major territorial acquisition made slavery and its expansion the center of numerous heated debates in both Houses.

General Zachary Taylor had won fame in the Mexican War and would ride his battlefield successes into the White House.

As the 12th US President, Taylor had succeeded his commander-in-chief, President James K. Polk, who had pressed

the nation into the Mexican War. President Polk, who had promised the nation that he would be a one term President, died of

cholera just three months after leaving office. Taylor, a Southerner but Unionist at heart, was now confronted with the results of his acclaimed generalship

during the recent conflict, but while in office he strived to appease both the North

and South on the issue of slavery through compromises, such as the Compromise of 1850. After Taylor died from illness just 500 days into office, future US Presidents would continue to pass the

mantle of compromises until President Abraham Lincoln assumed office in 1861 and issued a clarion sound on the subject

of slavery, leaving no doubt as to his position on the peculiar institution. A major result of the Mexican-American

War (1846-1848) was an acceleration of the American

Civil War, a conflict between the Northern and Southern states, which commenced in 1861, merely 13 years after the Mexican

Cession and at a cost of 620,000 American lives.

The Mexican Cession, formally Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, was a Treaty between the United States and Mexico that ended the Mexican

War. The Mexican Cession was signed at Villa de Guadalupe Hidalgo, which is located in northern Mexico City, the

capital of Mexico. The Treaty established the boundary between the United States and Mexico at the Rio Grande and the

Gila River. For a payment of $15,000,000, including $3,000,000 in civilian claims, the United States received from

Mexico more than 525,000 square miles (1,360,000 square km) of land, which form the present-day states of Arizona, California, Nevada,

New Mexico, Texas, and Utah. and portions of the present-day states of Oklahoma, Colorado, Kansas, and Wyoming.

Texas, however, bulked at the Mexican Cession. The Lone

Star State enjoyed a unique status because it was the only land included in the Mexican Cession that had already received

statehood from Washington some three years prior to the Treaty. Texans argued and claimed that it been a "republic" with

a recognized government several years prior to the Treaty, and to strengthen its position, Texas officials stated

that the United States had simultaneously annexed and granted it statehood on December 29, 1845, making it officially

part of the Union as the 28th US state, which was three years prior to the Cession. In fact, all parties were correct,

Texas was indeed a US state, but to formally establish the boundaries of Texas and to end hostilities and quell any future

legal proceedings, the United States officially included Texas in the Treaty with Mexico.

In return the United States agreed to settle the more than $3,000,000

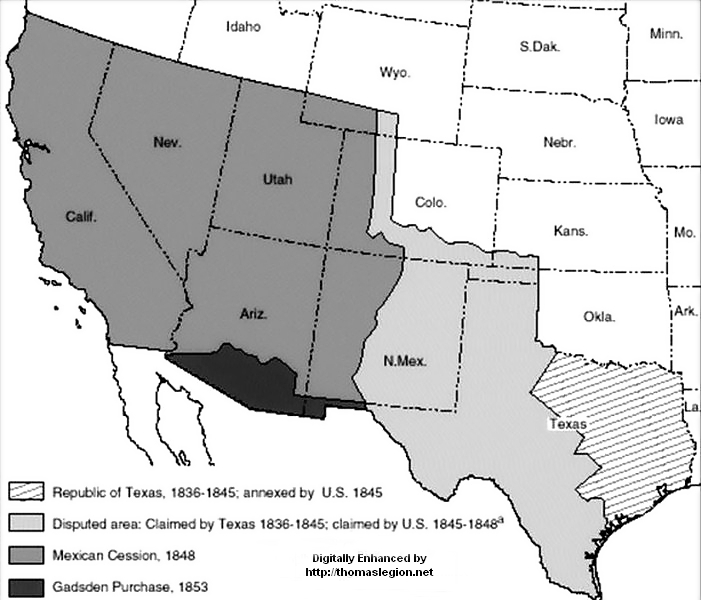

in claims made by U.S. citizens against Mexico. With this annexation, the continental expansion of the United States, spanning from

sea to shining sea, was completed, and five years later the United States purchased additional land from Mexico

in the Gadsden

Purchase of 1853. In just 72 years, and with the conclusion of the Mexican Cession at a total cost of $15,000,000,

the United States had grown geographically, economically, and militarily, and was a major player on the global stage, and

a nation that the world would henceforth recognize as a preeminent power.

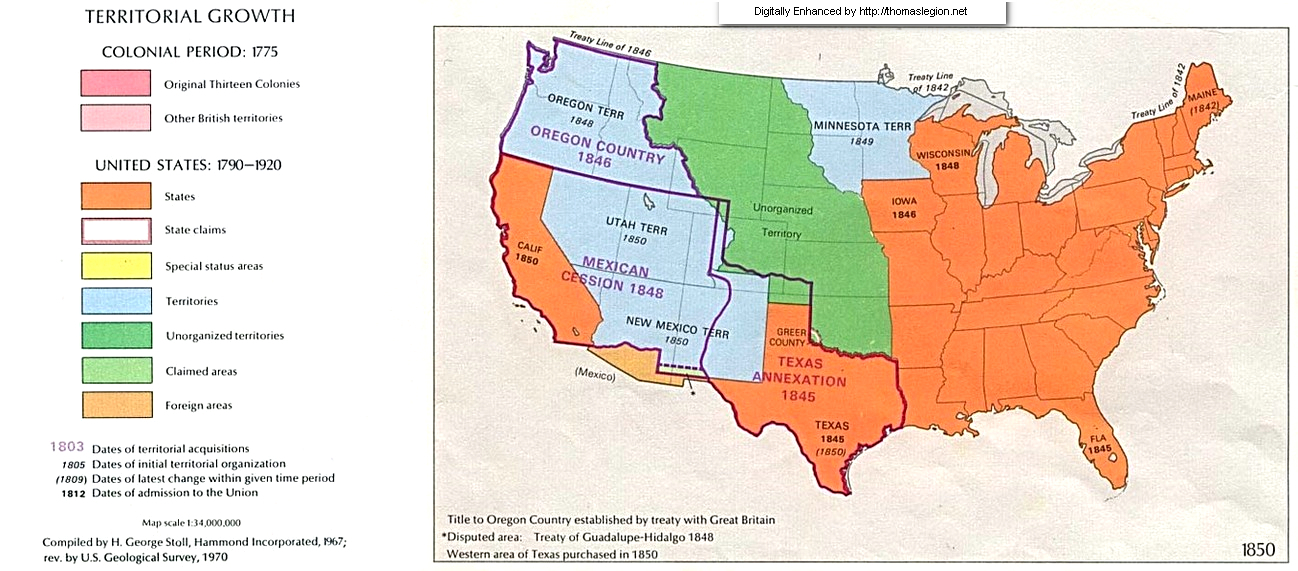

| Mexican Cession Superimposed on United States Map |

|

| US States added with Mexican Cession Map. Republic of Texas, Mexican Cession, and United States Map. |

| US Territory Gained in Mexican Cession Treaty Map |

|

| Mexican Cession Treaty Map and United States Map |

| Mexican Cession Map, Mexican Treaty with US |

|

| States and Land acquired by US in Mexican Cession Map |

Summary

The Mexican Cession contains 23 articles and was signed by the United

States and Mexico at Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848, amended and ratified by the U.S. Senate on March 10, 1848, ratified

by the President of the United States on March 16, 1848, exchanged with Mexico on May 30, 1848, and proclaimed on July 4,

1848.

The Mexican Cession of 1848 is an informal name given to the 1848 Treaty

of Guadalupe Hidalgo involving a land for cash transaction between the United States and Mexico at the conclusion

of the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). With the U.S. victory over Mexican forces in 1848 and the surrender of

Mexico City, the capital, Mexico entered into formal negotiations with the United States to end the war.

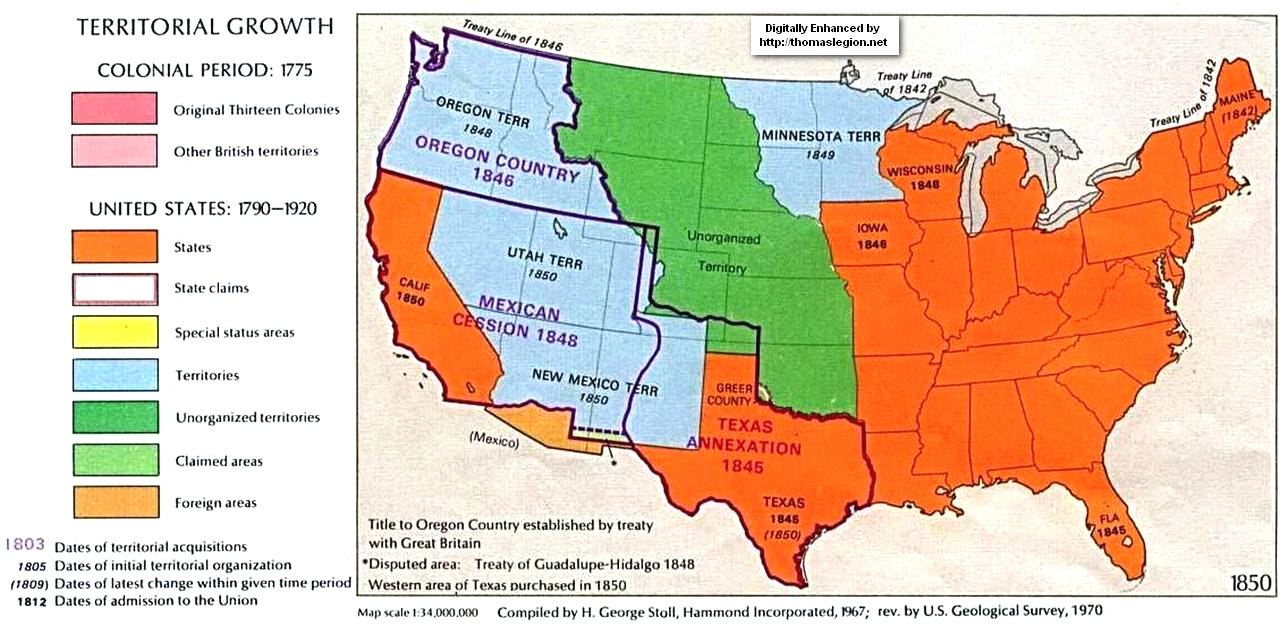

During his tenure, U.S. President James K. Polk oversaw the greatest territorial

expansion of the United States to date. Polk accomplished this through the annexation of Texas in 1845, the negotiation of

the Oregon Treaty with Great Britain in 1846, and the conclusion of the Mexican-American War in 1848, which ended with the

signing and ratification of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in 1848.

In November 1835, the northern part of the Mexican state of Coahuila-Tejas

declared itself in revolt against Mexico's new centralist government headed by President Antonio López de Santa Anna. By February

1836, Texans declared their territory to be independent and that its border extended to the Rio Grande rather than the Rio

Nueces that Mexicans recognized as the dividing line. Although the Texans proclaimed themselves citizens of the Independent

Republic of Texas on April 21, 1836 following their victory over the Mexicans at the Battle of San Jacinto, Mexicans continued

to consider Tejas a rebellious province that they would reconquer someday.

In December 1845, the U.S. Congress voted to annex the Texas Republic and

soon sent troops led by General Zachary Taylor to the Rio Grande (regarded by Mexicans as their territory) to protect its

border with Mexico. The inevitable clashes between Mexican troops and U.S. forces provided the rationale for a Congressional

declaration of war on May 13, 1846.

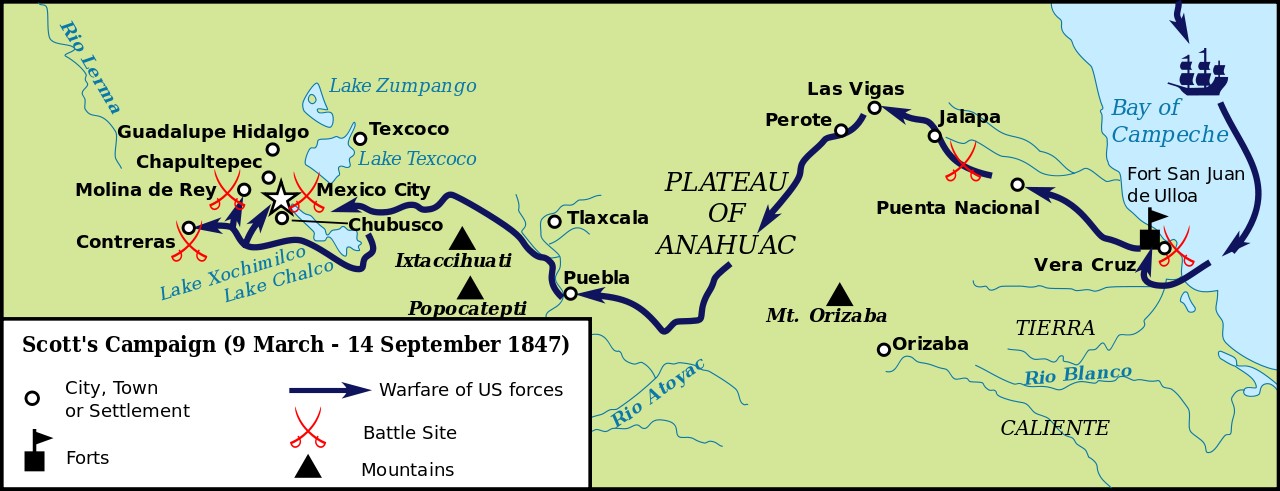

Hostilities continued for the next two years as General Taylor led his troops

through to Monterrey, and General Stephen Kearny and his men went to New Mexico, Chihuahua, and California. But it was General

Winfield Scott and his army that delivered the decisive blows as they marched from Veracruz to Puebla and finally captured

Mexico City itself in August 1847.

Mexican officials and Nicholas Trist, President Polk's representative, began

discussions for a peace treaty that August. On February 2, 1848 the Treaty was signed in Guadalupe Hidalgo, a city north of

the capital where the Mexican government had fled as U.S. troops advanced. Its provisions demanded that Mexico cede a

staggering 55% of its territory (present-day Arizona, California, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming)

in exchange for fifteen million dollars in compensation for war-related damage to Mexican property.

| On the Road to the Mexican Cession Map |

|

| Map showing General Winfield Scott's route to capture and occupy Mexico City |

| Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexican Cession Map |

|

| Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, aka Mexican Cession Map. Texas Revolution and Annexation Map. |

With its capital, Mexico City, captured and held by US forces, and General

Winfield Scott serving as "Governor of Mexico City," did Mexico have any alternative to the American demands? If pressed,

would the United States make greater demands on Mexico? While contemplating its options, Mexican authorities watched its citizens

descend into bloody Civil War. According to Mexican delegates who weighed the options carefully, Mexico had no alternative.

Other provisions stipulated the Texas border at the Rio Grande (Article V),

protection for the property and civil rights of Mexican nationals living within the new border (Articles VIII and IX), U.S.

promise to police its side of the border (Article XI), and compulsory arbitration of future disputes between the two countries

(Article XXI). When the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty in March, it reduced Article IX and deleted Article X guaranteeing

the protection of Mexican land grants. Following the Senate's ratification of the treaty, U.S. troops left Mexico City.

The terms of the Mexican Cession required the United States to pay

$15 million to Mexico and satisfy a maximum of $3.25 million in existing claims from U.S. citizens against

Mexico. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo demanded that the Rio Grande be recognized by Mexico as the boundary of Texas,

and it gave the United States ownership of California, and a vast area comprising the present-day states of New

Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Wyoming and Colorado. Mexicans in the annexed areas had the choice of relocating

to within Mexico's new boundaries or receiving American citizenship with full civil rights. More than 90% chose

the latter.

The U.S. Senate ratified the treaty by a vote of 38–14. The opponents

of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo were led by the Whigs, who had opposed the war and rejected Manifest Destiny in general,

and they believed that the U.S. Constitution made no allowances for expanding the nation's territory.

| 1848 Mexican Cession Map and State of Texas. |

|

| 1848 Mexican Cession Map, aka 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo Map. Texas Annexation, Statehood Map. |

| Mexican War and Battle of Resaca de la Palma |

|

| Mexican War and 2d US Dragoons slashing through the Mexican Army lines. |

Mexican War and Principal Battles Fought to Achieve Mexican Cession

| Palo Alto |

8 May 1846 |

| Resaca de la Palma |

9 May 1846 |

| Monterey |

21 September 1846 |

| Buena Vista |

22-23 February 1847 |

| Vera Cruz |

9-29 March 1847 |

| Cerro Gordo |

17 April 1847 |

| Contreras |

18-20 August 1847 |

| Churubusco |

20 August 1847 |

| Molino del Rey |

8 September 1847 |

| Chapultepec |

13 September 1847 |

Background

President James K. Polk (1845-1849) annexed the Republic of Texas within

his first year of office, but as a strong adherent of Manifest Destiny his primary objective was to acquire lands

and expand the existing borders of the United States. Texas annexation and statehood were simultaneously received

on December 29, 1845, making Texas the 28th U.S. state. The geographical boundaries of the Union had expanded immensely

with the addition of Texas, but Polk's grand strategy included expanding the nation's borders from sea to shining sea.

Immediately following the U.S. annexation of Texas, President Polk sent

a diplomat, John Slidell, to Mexico to negotiate three items:

- The border.

- Debts owed by the Mexican government to U.S. citizens.

- The purchase of California and New Mexico for as much as $50 million before

Mexico sold it to Great Britain.

Within four months of Texas receiving statehood, Mexico and the United

States would be at war.

The Mexican–American War (April 25, 1846–February 2, 1848), also

known as the Mexican War, followed in the wake of the contentious 1845 annexation of Texas, which Mexico claimed as

part of its sovereign territory, despite the 1836 Texas Revolution, or Texas War of Independence, which included

the famed Battle of the Alamo.

| US States added by Mexican Cession Treaty Map |

|

| States added to the United States by Mexican Cession Map. Texas, a US State, claimed exemption. |

A Humiliating Defeat

On September 14, 1847 the Mexican flag was not flying over the Mexican capital.

Instead, Mexico’s neighbor to the north had captured the country. How and why

did the United States defeat Mexico in the Mexican-American War? To the victors went what spoils? This essay will answer these

questions in a nutshell.

Throughout the 19th Century, the United States was increasing in

power and population while Mexico was stuck in chronic “political unrest, civil conflicts, depleted treasuries, [and]

separatist movements” (Oscar J. Martinez, Troublesome Border [Tucson: the University of Arizona Press, 1988],

51). The U.S. was also heavily influenced by Manifest Destiny—the idea that the U.S. had the natural right to rule North

America from coast to coast. Consequently, various presidential administrations in the 1820s and 30s sought to purchase land

from Mexico, with no avail.

In 1835, Texas battled and gained independence from Mexico; Texas was a sovereign

country for the next decade (the Lone Star Republic). In the Treaty of Velasco, the Texas-Mexico border was established along

the Rio Grande. Mexican President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna (pronounced “Santana”) signed the treaty but the

problem lied in the fact that the Mexican Congress did not ratify it, nor did Mexican presidents after Santa Anna acknowledge

Texas’ independence.

Texas was annexed by the United States in 1845. Mexico claimed the international

border to be the Nuecos River, while the U.S. claimed the border to be at the Rio Grande. The Nuecos River runs roughly parallel

to the Rio Grande about fifty to one-hundred miles northeast (the Texas side) of it. Therefore, by claiming their respective

river boundaries, both countries were trying to expand their territory. When the Mexican army crossed the Rio Grande and skirmished

with U.S. soldiers, President Polk declared that America had been invaded and American blood had been shed. These words meant

one thing, and it was war.

| Republic of Texas and Mexican Cession Map |

|

| Republic of Texas, Gadsden Purchase, Mexican Cession Map, aka Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo |

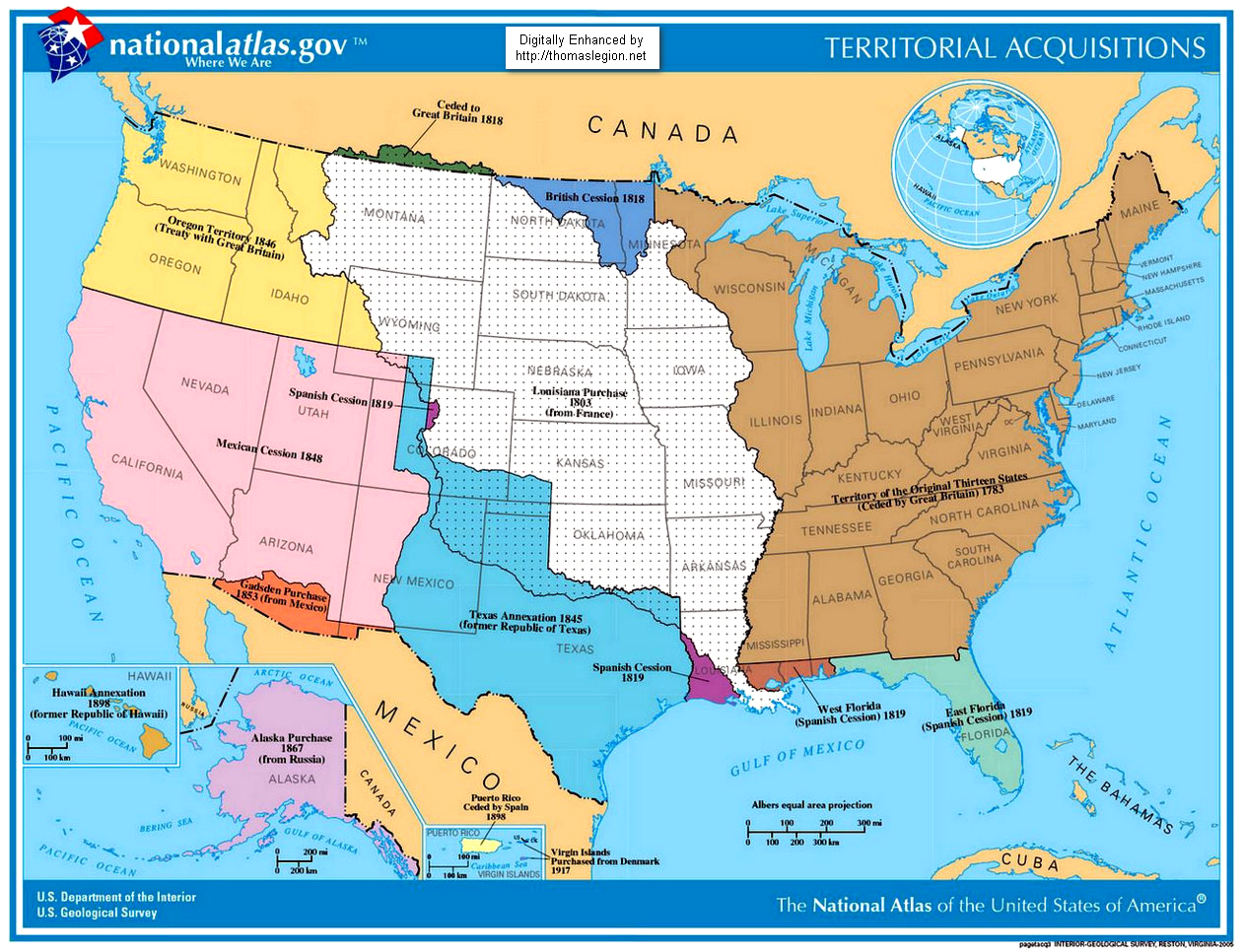

(Right) Coupled with the controversial Louisiana Purchase Agreement in 1803, the Mexican Cession in 1848 would expand and extend the nation's borders from sea to shining

sea. President Thomas Jefferson, having approved the Louisiana Purchase during his administration, had established the

precedent for the lands acquired in the 1848 Treaty. Jefferson

had agreed with political opposition on the fact that the U.S. Constitution did not contain explicit provisions

for acquiring territory, but, while he had long envisioned a nation bordered by the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, he also

understood that he had full treaty power and that was enough.

The Mexican–American War

was an embarrassment for Mexico and a goldmine for the United States, literally. Within days, the important port of Veracruz

was blockaded by the U.S. navy. The U.S. army fought their way overland into Mexico from California, Texas, and eventually

from Veracruz straight to the capitol. Mexico’s Santa Anna, back in power again, sent a peace treaty to Washington in

early 1847, but his terms were not approved. Later on that year, with U.S. troops just outside Mexico City, peace talks occurred.

When Mexico would not admit defeat and offer up territory, American troops invaded the capital city and quickly took control.

Santa Anna resigned as president and fled central Mexico in defeat. The United States now occupied the Mexican capital, thus

the U.S. occupied Mexico, now what could it take?

It was a long negotiation process that ultimately led to the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo

on February 2, 1848. President Polk sent “Peace Ambassador” Nicholas Trist to central Mexico in order to set the

terms of the Treaty. On a note of interest, Trist was recalled by Polk but disobeyed orders to go back to Washington; he was

the only American to sign the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. If Trist would have left for Washington like he was ordered to

do, the treaty would probably never have happened. With this Treaty, the American Southwest as we know it today officially

came under U.S. control and Mexico lost half of its country. The treaty established the Texas-Mexican border along the Rio

Grande; fifteen years later it would be the same river that led to the Chamizal dispute between Mexico and the United States.

It was agreed that a group of surveyors from each country, working together, would set out to map the new 2,000-mile long

border.

Just weeks after the treaty was signed, gold was discovered in California

(California was known for a long time as El Dorado, which means “the land of gold” in Spanish), leading to the

largest gold rush in the history of the United States. But unfortunately for Mexico, El Dorado was not part of Mexico anymore.

| Mexican Cession Map and US Expansionism |

|

| US Territorial Expansion at the Expense of Mexico Map. Republic of Texas and Texas Independence Map |

The Trist Treaty

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which brought an official end to the Mexican-American

War (1846–48), was signed on February 2, 1848, at Guadalupe Hidalgo, a city to which the Mexican government had fled

with the advance of U.S. forces.

With the defeat of its army and the fall of the capital, Mexico City, in September

1847, the Mexican government surrendered to the United States and entered into negotiations to end the war. The peace talks

were negotiated by Nicholas Trist, chief clerk of the State Department, who had accompanied General Winfield Scott as a diplomat

and President Polk's representative. Trist and General Scott, after two previous unsuccessful attempts to negotiate a treaty

with President Santa Anna, determined that the only way to deal with Mexico was as a conquered enemy. Nicholas Trist negotiated

with a special commission representing the collapsed government led by Don Bernardo Couto, Don Miguel Atristain, and Don Luis

Gonzaga Cuevas.

President Polk had recalled Trist under the belief that negotiations would

be carried out with a Mexican delegation in Washington. In the six weeks it took to deliver Polk's message, Trist had received

word that the Mexican government had named its special commission to negotiate. Trist determined that Washington did not understand

the situation in Mexico and negotiated the peace treaty in defiance of the President.

In a December 4, 1847, letter to his wife, he wrote, "Knowing it to be the

very last chance and impressed with the dreadful consequences to our country which cannot fail to attend the loss of that

chance, I decided today at noon to attempt to make a treaty; the decision is altogether my own."

| Mexican Cession Map and Growth of United States. |

|

| Map of Mexican Cession and other territorial acquisitions of the United States |

| Texas Revolution and Texas War of Independence Map |

|

| Texas Independence and Republic of Texas Map |

Mexican Cession and Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (gwah-dah-loop-ay ee-dahl-go), which brought an official end to the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) was signed on February 2, 1848, at

Guadalupe Hidalgo, a city north of the capital where the Mexican government had fled with the advance of U.S. forces.

With the defeat of its army and the fall of the capital, Mexico City, in September

1847 the Mexican government surrendered to the United States and entered into negotiations to end the war. The peace talks

were negotiated by Nicholas Trist, chief clerk of the State Department, who had accompanied General Winfield Scott as a diplomat

and President Polk's representative. Trist and General Scott, after two previous unsuccessful attempts to negotiate a treaty

with Santa Anna, determined that the only way to deal with Mexico was as a conquered enemy. Nicholas Trist negotiated with

a special commission representing the collapsed government led by Don Bernardo Couto, Don Miguel Atristain, and Don Luis Gonzaga

Cuevas of Mexico.

In The Mexican War, author Otis Singletary states that President

Polk had recalled Trist under the belief that negotiations would be carried out with a Mexican delegation in Washington. In

the six weeks it took to deliver Polk's message, Trist had received word that the Mexican government had named its special

commission to negotiate. Against the president's recall, Trist determined that Washington did not understand the situation

in Mexico and negotiated the peace treaty in defiance of the president. In a December 4, 1847, letter to his wife, he wrote,

"Knowing it to be the very last chance and impressed with the dreadful consequences to our country which cannot fail to attend

the loss of that chance, I decided today at noon to attempt to make a treaty; the decision is altogether my own."

In Defiant Peacemaker: Nicholas Trist in the Mexican War, author

Wallace Ohrt described Trist as uncompromising in his belief that justice could be served only by Mexico's full surrender,

including surrender of territory. Ignoring the president's recall command with the full knowledge that his defiance would

cost him his career, Trist chose to adhere to his own principles and negotiate a treaty in violation of his instructions.

His stand made him briefly a very controversial figure in the United States.

Under the terms of the treaty negotiated

by Trist, Mexico ceded to the United States Upper California and New Mexico. This was known as the Mexican Cession and included

present-day Arizona and New Mexico and parts of Utah, Nevada, and Colorado (see Article V of the treaty). Mexico relinquished

all claims to Texas and recognized the Rio Grande as the southern boundary with the United States (see Article V).

| Mexican Cession and Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo |

|

| Mexican-American War and Mexican Cession |

The United States paid Mexico $15,000,000 "in consideration of the extension

acquired by the boundaries of the United States" (see Article XII of the treaty) and agreed to pay American citizens debts

owed to them by the Mexican government (see Article XV). Other provisions included protection of property and civil rights

of Mexican nationals living within the new boundaries of the United States (see Articles VIII and IX), the promise of the

United States to police its boundaries (see Article XI), and compulsory arbitration of future disputes between the two countries

(see Article XXI).

Trist sent a copy to Washington by the fastest means available, forcing

Polk to decide whether or not to repudiate the highly satisfactory handiwork of his discredited subordinate. Polk chose to

forward the treaty to the Senate. When the Senate reluctantly ratified the treaty (by a vote of 34 to 14) on March 10, 1848,

it deleted Article X guaranteeing the protection of Mexican land grants. Following the ratification, U.S. troops were removed

from the Mexican capital.

To carry the treaty into effect, commissioner Colonel Jon Weller and surveyor

Andrew Grey were appointed by the United States government and General Pedro Conde and Sr. Jose Illarregui were appointed

by the Mexican government to survey and set the boundary. A subsequent treaty of December 30, 1853, altered the border from

the initial one by adding 47 more boundary markers to the original six. Of the 53 markers, the majority were rude piles of

stones; a few were of durable character with proper inscriptions.

Over time, markers were moved or destroyed, resulting in two subsequent

conventions (1882 and 1889) between the two countries to more clearly define the boundaries. Photographers were brought in

to document the location of the markers. These photographs are in Record Group 77, Records of the Office of the Chief Engineers,

in the National Archives.

Aftermath

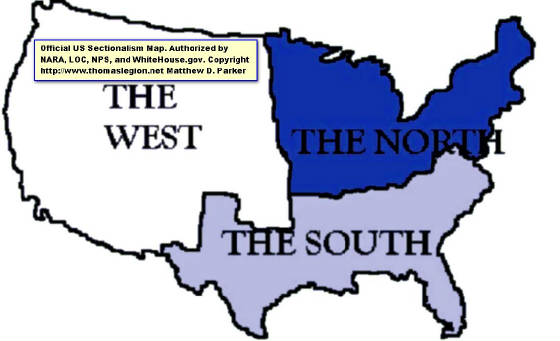

Until 1850 the nation had hosted 15 free and 15 slave states, creating a balance between

proslavery and free states. But with the Mexican Cession in 1848, formally the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the nation purchased territory that forms the present-day US states of California, Nevada, Utah, most

of Arizona, about half of New Mexico, about a quarter of Colorado, and a small section of Wyoming. When California was admitted

to the Union as a free state in 1850, the United States soon added three additional free states with Minnesota in

1858, Oregon in 1859, and Kansas in 1861. No slave states were added to the United States during that time,

so the nation was now confronted with an imbalance of power between slave and free states, known as sectionalism, which served only to fuel existing

tensions between the North and South. The Mexican Cession of 1848 resulted in the Compromise of 1850 and the rapid shift in political power and influence. Because the Compromise of 1850 fanned the flames of sectionalism, in

just eleven years, 1861, the nation would be engaged in bloody Civil War.

| 1848 Mexican Cession Map Superimposed over US |

|

| US States Added by Mexican Cession Map. Mexican Cession Overlaid on United States Map. Map to Scale. |

| US Territorial Acquisitions & Mexican Cession Map |

|

| Land Acquired by the US Map, including Mexican Cession and Texas |

| North and South Sectionalism Map |

|

| US Sectionalism Map and Mexican Cession |

Analysis

The Annexation of Texas, the Mexican-American War, and the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo,

1845–1848.

The Mexican-American War, which resulted in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo,

was caused by the annexation and statehood of Texas by the United States. The Mexican War was "one of the

most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of

European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory." Words of General

of the Union Army and Eighteenth President of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant

By simultaneously annexing and granting statehood to Texas on December

29, 1845, the United States had intentionally provoked Mexico, a nation that had never recognized the existence of the Republic of Texas, to war. After Texas entered into the Union as the 28th state, a state of war

would exist between Mexico and the United States in merely 117 days, resulting in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the

largest land acquisition (including Texas) in the history of the United States.

The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, ended the war between the United

States and Mexico. By its terms, Mexico ceded 55 percent of its territory to the United States, which expanded the nation

from coast to coast enabling it to become a global power that could no longer be ignored on the world stage.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, or Mexican Cession, was signed

by the United States and Mexico on February 2, 1848, ending the Mexican War and extending the boundaries of the United States

by over 525,000 square miles. In addition to establishing the Rio Grande as the border

between the two countries, the territory acquired by the U.S. included what would become the states of Texas, California,

Nevada, Utah, most of New Mexico and Arizona, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming. By being a signatory of the Cession, Mexico

also formally acknowledged the State of Texas and its boundaries. In exchange Mexico received fifteen million dollars

in compensation for ceding the majority of its territory to the United States, and the U.S. agreed to assume claims from

private citizens of these areas against the Mexican government.

| Mexican Cession Treaty, Texas, and United States |

|

| Mexican Cession Superimposed over US States Map. US Geological Survey Map. |

During his tenure, U.S. President

James K. Polk oversaw the greatest territorial expansion of the United States to date. Polk accomplished this through

the annexation of Texas in 1845, the negotiation of the Oregon Treaty with Great Britain in 1846, and the conclusion of the

Mexican-American War in 1848, which ended with the signing and ratification of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in 1848.

These events brought within the control of the United States the future

states of Texas, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Washington, and Oregon, as well as portions of what would

later become Oklahoma, Colorado, Kansas, Wyoming, and Montana.

Following Texas’ successful war of independence against Mexico in

1836, President Martin van Buren refrained from annexing Texas because the Mexicans threatened war. Accordingly, while

the United States extended diplomatic recognition to Texas, it took no further action concerning annexation until 1844, when

President John Tyler restarted negotiations with the Republic of Texas. His efforts culminated on April 12 in a Treaty of

Annexation, an event that caused Mexico to sever diplomatic relations with United States. Tyler, however, lacked the votes

in the Senate to ratify the treaty, and it was defeated by a wide margin in June. Shortly before he left office, Tyler tried

again, this time through a joint resolution of both houses of Congress. With the support of President-elect Polk, Tyler managed

to get the joint resolution passed on March 1, 1845, and Texas was admitted into the United States on December 29.

While Mexico did not follow through with its threat to declare war if the

United States annexed Texas, relations between the two nations remained tense due to Mexico’s disputed border with Texas.

According to the Texans, their state included significant portions of what is today New Mexico and Colorado, and the western

and southern portions of Texas itself, which they claimed extended to the Rio Grande River. The Mexicans, however, argued

that the border only extended to the Nueces River, several miles to the north of the Rio Grande.

In July, 1845, Polk, who had been elected on a platform of expansionism,

ordered the commander of the U.S. Army in Texas, Zachary Taylor, to move his forces into the disputed lands that lay between

the Nueces and Rio Grande rivers. In November, Polk dispatched Congressman John Slidell to Mexico with instructions to negotiate

the purchase of the disputed areas along the Texas-Mexican border, and the territory comprising the present-day states of

New Mexico and California.

Following the failure of Slidell’s mission in May 1846, Polk used

news of skirmishes between Mexican troops and Taylor’s army to gain Congressional support for a declaration of war against

Mexico. The President neglected to inform Congress, however, that the Mexicans had used force only after Taylor’s troops

had positioned themselves on the banks of the Rio Grande River, which was effectively Mexican territory. On May 13, 1846,

the United States declared war on Mexico.

| Mexican Cession Map and the 48 US States. |

|

| Mexican Cession Map and the United States Map |

Following the capture of Mexico City in September 1847, Nicholas Trist,

chief clerk of the Department of State and Polk’s peace emissary, began negotiations for a peace treaty with the Mexican

Government under terms similar to those pursued by Slidell the previous year. Polk soon grew concerned by Trist’s conduct,

however, believing that he would not press for strong enough terms from the Mexicans, and because Trist became a close friend

of General Winfield Scott, a Whig who was thought to be a strong contender for his party’s presidential nomination for

the 1848 election. Furthermore, the war had encouraged expansionist Democrats to call for a complete annexation of Mexico.

Polk recalled Trist in October.

Believing that he was on the cusp of an agreement with the Mexicans, Trist

ignored the recall order and presented Polk with the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, which was signed in Mexico City on February

2, 1848. Under the terms of the treaty, Mexico ceded to the United States approximately 525,000 square miles (55% of its prewar

territory) in exchange for a $15 million lump sum payment, and the assumption by the U.S. Government of up to $3.25 million

worth of debts owed by Mexico to U.S. citizens.

While Polk would have preferred a more extensive annexation of Mexican territory,

he realized that prolonging the war would have disastrous political consequences and decided to submit the treaty to the Senate

for ratification. Although there was substantial opposition to the treaty within the Senate, on March 10, 1848, it passed

by a razor-thin margin of 38 to 14.

The war had another significant

outcome. On August 8, 1846, Congressman David Wilmot introduced a rider to an appropriations bill that stipulated that “neither

slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist” in any territory acquired by the United States in the war against

Mexico. While Southern senators managed to block adoption of the so-called “Wilmot Proviso,” it nonetheless provoked

a political firestorm. The question of whether slavery could expand throughout the United States continue to fester until

the defeat of the Confederacy in 1865.

Related Reading:

|

|

|