|

The Beginning

New Bern served as one of the major outposts for the Union Army and as a

fortified garrison in the midst of enemy territory. The town was occupied by the Union troops from 1862-1865 when the Civil

War ended. Several large camps for Union regiments had developed around the communities of New Bern that housed many of the

Union soldiers. These camps also provided protection in the perimeter of New Bern, where some of the ranking commanders had

established their living quarters.

There were two events in the New Bern area during the Civil War. The Battle

of New Bern took place in early 1862, and a demonstration on New Bern occurred in 1863. An attack on the city was planned

in early 1864, but never materialized.

Battle of New Bern

| Civil War Battle of New Bern, North Carolina, |

|

| Battle of New Bern Map |

| Battle of New Bern |

|

| New Bern Civil War Marker |

Federal plans for a strike at the North Carolina coast were made in the

fall of 1861. Brigadier General Ambrose E. Burnside was chosen to command an amphibious army division to be composed of New

England men “adapted to coast service.” He was authorized to raise 15 regiments and was given unlimited funds

for equipment; thereby, the first major amphibious force in United States history was born. While his troops were being assembled

at Annapolis, Maryland, Burnside labored in New York to secure transports. He had to settle for a “motley fleet.”

The vessels were ordered to rendezvous at Fortress Monroe in Virginia. The transports on their way down were to stop at Annapolis

and take on board the troops assembled there. The ships finally arrived at Annapolis on January 4, 1862. Burnside started

embarking his troops on that date. On January 7, General George B. McClellan, general-in-chief of the Federal armies, sent

from Washington the official orders for the campaign. Burnside organized his forces into three brigades and placed Brigadier

Generals John G. Foster, Jesse L. Reno, and John G. Parke in command. On the morning of January 9, aware of the role he was

playing, Burnside gave the order for his transports to get underway. The soldiers did not know their destination. Ship captains

were even given sealed orders to be opened at sea. They went to sea on the night of January 11, Rear Admiral Louis M. Goldsborough

commanding the naval vessels in the expedition. Most of the vessels had little difficulty getting over the outer bar at Hatteras

Inlet but getting across the shallow shoals and into Pamlico Sound was difficult. For almost two weeks, Hatteras was lashed

by one storm after another. The violent storms of mid-January cost Burnside several of his ships. Losses included the Louisiana,

City of New York, Grapeshot, Zouave, and Pocahontas, the latter with one hundred horses aboard. From aboard the Picket, Burnside

superintended his fleet of transports, performing all of the duties of a harbor master. To the relief of both Goldsborough

and Burnside, the weather cleared on the 26th, and by February 4, the entire fleet was safely anchored in the sound. In a

matter of seven days, the Burnside-Goldsborough command had captured Roanoke Island, occupied two coastal towns, blocked up

a vital canal, and destroyed the Confederate navy in the sounds.

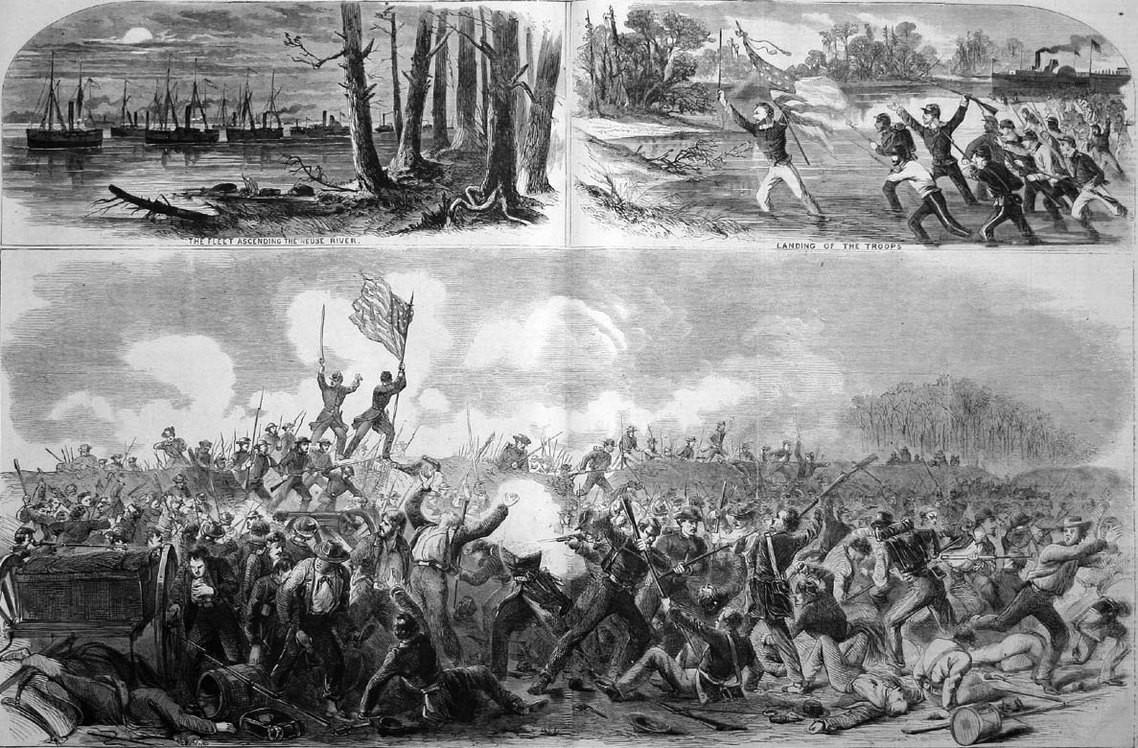

| Battle of New Bern |

|

| Harper's Weekly, April 5, 1862, pp. 216-217. |

Part 2 of the Burnside expedition was the Battle of New Bern. Confederate

General L. O. Branch had approximately 4,000 untried troops, not nearly enough to man the elaborate set of defenses below

the city. Branch had arrived at New Bern in November 1861. Since most fortifications had been constructed before his arrival,

it took him six weeks to make the necessary changes to contract them. He was greatly hampered in this work by a scarcity of

implements, tools, and Negro labor. He was still able to strengthen the fortification he intended to hold. The line over which

the battle was to be fought began with Fort Thompson, a 13-gun sod installation anchored on the Neuse, about six miles below

New Bern. From Fort Thompson, the Confederate line stretched westward for approximately one mile to the Atlantic and North

Carolina Rail-road. General Branch found it necessary to shorten his lines because of his small force. This readjustment left

an unprotected gap of 150 yards in the defenses at Wood’s brickyard along the railroad. In early March, the New Bern

defenses were inspected by General Richard C. Gatlin and a board of officers who concurred in General Branch’s decision

to defend only the Fort Thompson line; provided that the brickyard was protected. On March 11, General Burnside completed

the embarkation of his approximately 11,000 troops at Roanoke Island and set sail for Hatteras. Admiral Goldsborough received

orders to proceed at once to Hampton Roads and turned over command of the North Carolina sounds to Commander Stephen C. Rowan.

Under its new commander, the Federal fleet continued a course toward the North Carolina mainland. By 9 p.m., the fleet had

come to anchor off the mouth of Slocum Creek, about 12 miles below New Bern by water and 17 by land. The arrival of the Federal

fleet was signaled to the Confederate outposts up and down the river by means of large bonfires. At daybreak on March 13,

Federal gunboats commenced a bombardment of the shore at Slocum’s Creek in preparation for the disembarkation of troops.

The shelling was unnecessary, as no Confederates were in the immediate area. General Burnside then landed his troops.

| Civil War North Carolina Coast Map |

|

| (Civil War Outer Banks Map |

Once on the mainland, they started a miry journey towards New Bern. General

Burnside was ready to take the offensive on the morning of March 14. For the advance, Burnside divided his force into three

columns. General Foster commanded on the right between the river and the railroad, General Reno on the left of the railroad,

and General Parke in reserve along the rail-road, ready to aid either column. Without waiting for General Reno to get into

position, Foster made contact with the Confederate left and was greeted with a shell from Latham’s Battery. The fight

then began “in earnest” at about 8 a.m. From their breastworks Confederate infantrymen opened an “incessant”

and “severe” fire. Commander Rowan knew that he was endangering the lives of men in his own army; yet he kept

up heavy fire. His offense stymied, Foster called up reserves. Withering fire could not break the Confederate line. As a consequence,

the Federal offensive on the right came to a standstill. On the left General Reno also encountered great difficulties but

his lead regiment, the 21st Massachusetts, discovered the break in the Confederate line at the brick kiln. General Branch

had ordered two heavy guns into position to cover this fatal exposure, but the pieces were not in place when the fight started.

No Confederates were on Reno’s immediate front for Colonel Zebulon B. Vance’s line did not extend to the railroad.

Seizing the opportunity to flank the Confederate line, Reno formed the 21st Massachusetts at right angles to his line of march

and personally led four of its companies in a charge across the rail-road against the militia. Upon seeing the enemy on their

flank, the militiamen were seized with panic and part of them broke ranks. Colonel H. J. B. Clark of the militia ordered a

retreat.

The flight of the militiamen exposed the right flank of Colonel J. Sinclair’s 35th North Carolina.

Colonel R. D. Campbell ordered the 35th out of the breastworks but, according to Campbell, Sinclair failed to form his men

and left the field in confusion. Before General Reno could lead the rest of his regiment across the railroad, Major A. B.

Carmichael commanding Vance’s left, opened up a deliberate fire. General Branch, meanwhile, ordered Colonel C. M. Avery’s

regiment of reserves to the support of Vance’s 26th North Carolina and to seal up the break in the line. Four of Avery’s

companies under Major Gaston Lewis repulsed the enemy time and again, and twice charged them with detachments of companies

and each time made them flee. The destructive fire of Lewis and Avery prevented General Reno from throwing more troops across

the railroad and forced him to hurry his other regiments into line on Vance’s front. This left the four companies of

the 21st Massachusetts under Lieutenant Colonel W. S. Clark alone be-hind the Confederate line. Facing his 200 men toward

Fort Thompson, he gave the command “charge bayonets” and in a matter of minutes two guns of Brem’s Battery

were in Federal hands. By this time, Colonel Campbell had taken the 7th North Carolina out of the breastworks and ordered

it to charge Clark’s advancing column. The order was successfully carried out, with the New Englanders beating a hasty

retreat to the railroad.

| Confederate Line of Battle at New Bern, NC |

|

| Confederate Forces Await Imminent Union Attack |

The Confederate front was later restored. It was after 11 a.m. and the battle had been raging since eight.

The right and left of the Confederate line were still intact, but the unfortified center was seriously menaced by the flight

of the militia and the 35th. General Branch decided his next priority was to secure the retreat. Orders to retire across the

Trent River bridge were dispatched to Colonels Avery and Vance. Unfortunately, the couriers never delivered the messages and

Colonel Avery and 200 of his men were captured. The remainder of Avery’s command under Colonel Robert F. Hoke made it

safely to the west bank of Brice’s Creek. Colonel Vance, with the 26th North Carolina fled across the swamp to his right

to escape capture. The remaining North Carolina regiments withdrew across the Trent River bridge into New Bern. Every man

struck out for the bridge. Once across, some soldiers did not stop running until they had climbed aboard a west bound train

just pulling out of the New Bern depot. The bridge over the Trent, already prepared for destruction, was set on fire as the

last of Branch’s command passed over. Realizing that it would be impossible to hold New Bern, General Branch directed

all the officers he could find to conduct the remnants of the army to the rail depot at Tuscarora. There arrangements could

be made for their transportation to Kinston. By this time parts of New Bern were aflame. There is little reason to think that

General Branch ordered the town fired. In his official report he stated that New Bern was “in flames in many places”

when he arrived from the battlefield. Adjutant James A. Graham of the 27th North Carolina wrote his mother soon after the

battle, “We saw we could not hold it and therefore set the town on fire and retreated to this place (Kinston).”

From the statements of Branch and Graham, it can be assumed that New Bern was burned by the retreating Confederate soldiers

who acted on their own initiative, not on orders from their commanding general. The fires fortunately did comparatively little

damage.

| North Carolina Civil War Map |

|

| North Carolina Civil War Battle of New Bern Map |

New Bern, in the meantime, had been occupied by the victorious Federal army.

During the afternoon of the fourteenth, the soldiers were ferried across the Trent River to take possession of their prize.

General Burnside selected a stately home in New Bern for his headquarters, but when an aide went to get the home in order,

he found it in the process of being plundered by soldiers, sailors, and Negroes. To halt the pillaging in New Bern, General

Burnside brought a strong garrison into town and made guards available for those who wanted protection.

The loss of New Bern, regardless of the cause, was a great blow to North

Carolina. It did result, however, in the Confederate officials’ reevaluating the state scene. To prevent a Federal push

into the interior, Confederate troops were rushed into North Carolina from Virginia. North Carolina’s defenses were

strengthened further by a change in high command. General Richard C. Gatlin was relieved from duty and President Jefferson Davis gave the post to Major

General Theophilus H. Holmes, North Carolina’s ranking general in the Confederacy.

Demonstration of New Bern

On February 25, 1863, Lieutenant General James Longstreet replaced Major

General Gustavus Smith as commander of the Departments of Virginia and North Carolina. It was his intention to protect the

supply lines in eastern North Carolina and at the same time gather provisions from that fertile region. In pursuit of this

plan, General D. H. Hill, Longstreet’s subordinate in North Carolina, planned demonstrations on New Bern and Wilmington.

General Hill assumed command of the troops in North Carolina on February 25. In compliance with his request for more troops,

Longstreet instructed General W. H. C. Whiting at Wilmington to reinforce Hill with 4,000 men.

The opening round in the Confederate attack on New Bern occurred on March

13 when Brigadier General Junius Daniel’s scouts, moving along the “lower Trent road” encountered enemy

pickets about ten miles from the city. The Federals were easily pushed back two miles to a line of works at Deep Gully. Following

a bombardment of the Federal position, General Daniel led four companies in a successful charge on the enemy works. The Federals

made no attempt at a recapture of Deep Gully until daybreak the next morning. Repulsed in this attempt, the Federal troops

retired under orders to the main defenses at New Bern. Difficulties encountered at Fort Anderson were to doom the Confederate

chances of taking New Bern. Fort Anderson, garrisoned by the 92nd New York, Lieutenant Colonel Hiram Anderson, Jr., commanding,

was an earthwork on the north bank of the Neuse directly opposite New Bern. It was flanked on both sides by swamps and was

approachable only in front along a narrow causeway. At dawn on the morning of the 14th, Brigadier General James Johnston Pettigrew

rushed his command across this causeway and, with light batteries, opened fire on the fort. Fearful that a charge on the Federal

works would cost him between 50 and 100 men, he decided to deploy his force, demoralize the enemy by a heavy fire, and then

demand surrender. The surrender demand proved a serious mistake. General B. H. Robertson, under orders to cut the railroad,

fared little better than Pettigrew. The failure of Robertson and Pettigrew caused General Hill to withdraw his forces from

New Bern. Many of Hill’s men had serious doubts as to whether their Commanding General had any “real object”

in mind when he started the expedition.

| Satellite View of New Bern, North Carolina |

|

| Battle of New Bern. Map courtesy Microsoft Virtual Earth (3D) |

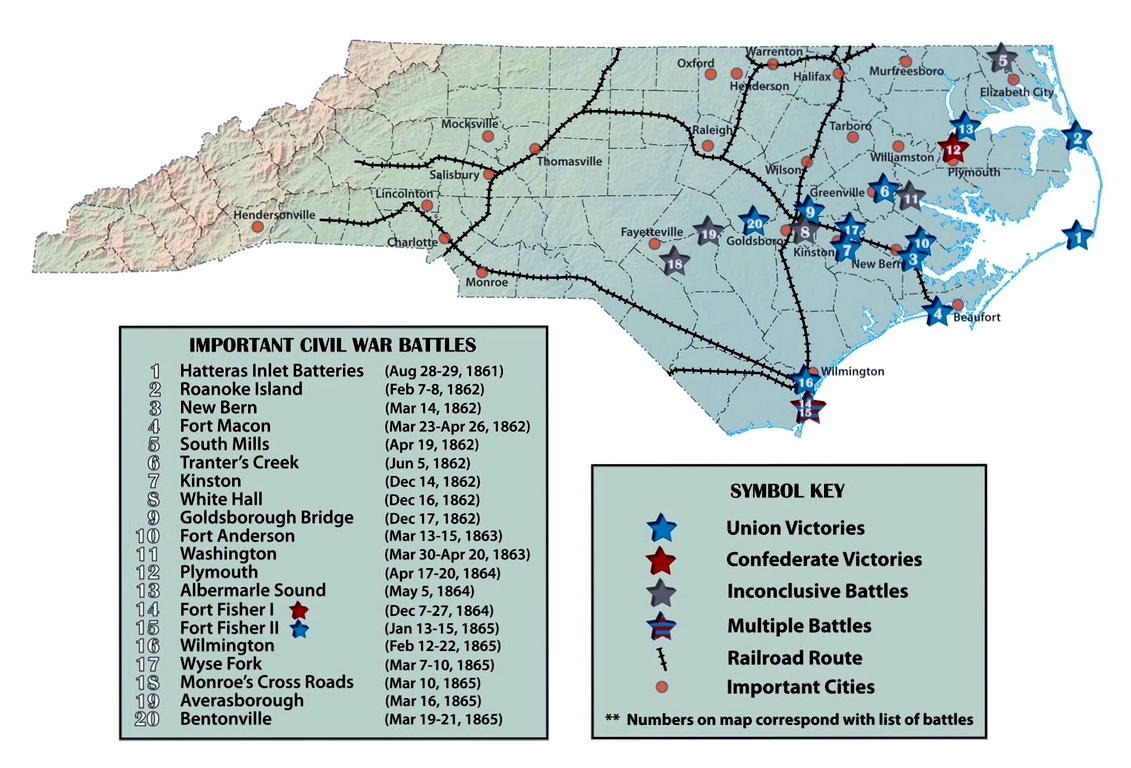

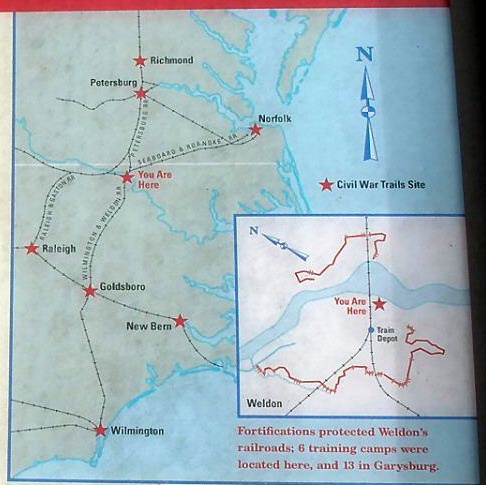

| Critical Defenses of Wilmington Weldon Railroad |

|

| Civil War on the North Carolina Coast |

| North Carolina Civil War Battlefield Map |

|

| Map of North Carolina Civil War Battles |

Attack on New Bern

On January 2, 1864, General Robert E. Lee, aware of the critical state of

affairs in North Carolina, wrote President Jefferson Davis that if an attempt could be made to capture the enemy’s forces

at New Bern, it should be done. A large amount of provisions and other supplies were said to be at New Bern, which were much

wanted for his army. Davis willingly approved of Lee’s plan. Major General George E. Pickett was selected to command

the operation. President Davis selected his own aide, Commander John Taylor Wood, to command the cooperating naval force.

A force of about 13,000 men and 14 navy cutters were soon concentrated at

Kinston, North Carolina. Pickett divided his troops into three columns and, on the morning of January 30, moved off in the

direction of New Bern. His plan of operation called for Brigadier General Seth M. Barton with his own brigade, that of Brigadier

General J. L. Kemper, and three regiments of Matt Ransom’s, eight rifled pieces, six napoleons, and 600 cavalry to cross

the Trent River near Trenton and proceed on the south side of the river to Brice’s Creek below New Bern. A simultaneous

assault by these three columns on the defenses of New Bern was planned for February 1. The night before, Commander Wood was

to descend the Neuse, endeavor to surprise and capture the gun-boats in that river and then cooperate with the land forces

in their attack on New Bern.

General R. F. Hoke went into camp on the night of the 31st at Steven’s

Fork, a point approximately two miles from New Bern and two from a Federal outpost. Hoke moved forward quickly in order to

reach Batchelder’s Creek before the bridge could be taken up, but he arrived too late. Finding the bridge destroyed

and the enemy strongly entrenched, the General decided to wait until dawn before continuing his advance. He expected the enemy

to throw troops by cars across the creek on the railroad. If this happened, he planned to rush forward toward New Bern, cut

the track, capture the train, and enter the city by rail. The Federals did as Hoke anticipated, but the General missed his

prize by five minutes. Warned by telegraph of Hoke’s moves, the enemy rushed the train back to New Bern. With the break

of day, Hoke threw some trees across the creek and crossed two regiments over. He hoped to avoid the loss of men by storming.

In the meantime, the enemy had received reinforcements from New Bern and was in a position to offer stout resistance. Still

Hoke “routed them” once he got his troops across the creek. Following this engagement, the Confederates moved

on to within a mile of New Bern, where a halt was called to await the sound of Barton’s guns from the opposite side

of the Trent River. Before leaving Kinston, Barton strengthened the picket line between the Neuse and the Trent and had cavalry

detachments out covering all the roads and paths south and east of Kinston. When the enemy works came into view around 8 a.m.

on the 1st, Barton immediately advanced a line of skirmishers close to Brice’s Creek. In company with General Ransom

and Colonel William R. Aylett, Barton made a reconnaissance, finding many obstacles. General Barton concluded that he was

unprepared to encounter obstacles so serious. He immediately dispatched messengers, scouts and couriers to General Pickett

informing him and asking instructions. The Commanding General dispatched Captain Robert A. Bright of his staff to communicate

with Barton. Barton was ordered to join the troops before New Bern for an assault on that front. To get across the Trent,

Barton had to retrace his steps to Pollocksville, at which place on February 3 he received new orders directing him to Kinston.

General Pickett decided to abandon the entire New Bern operation when he learned that Barton could not join him until the

4th, if then. The General withdrew his forces from New Bern on the third. He bungled the New Bern operation. The coordinated

attack on the city, as outlined by Hoke, never materialized.

Sources: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; Battle of New Berne Map is

courtesy the Library of Congress; Satellite Image courtesy Microsoft Virtual Earth (3D).

Recommended Reading:

The Civil War on the Outer Banks: A History of the Late Rebellion Along the Coast of

North Carolina from Carteret to Currituck With Comments on Prewar Conditions and an Account of (251 pages). Description: The ports at Beaufort, Wilmington, New Bern and Ocracoke, part

of the Outer Banks (a chain of barrier islands that sweeps down the North Carolina coast from the Virginia Capes to Oregon

Inlet), were strategically vital for the import of war materiel and the export of cash producing crops. From official

records, contemporary newspaper accounts, personal journals of the soldiers, and many unpublished manuscripts and memoirs,

this is a full accounting of the Civil War along the North

Carolina coast.

Recommended Reading: The

Civil War in Coastal North Carolina (175 pages) (North Carolina Division of Archives and History). Description: From the drama of blockade-running to graphic descriptions of battles

on the state's islands and sounds, this book portrays the explosive events that took place in North Carolina's

coastal region during the Civil War. Topics discussed include the strategic importance of coastal North Carolina, Federal occupation of coastal areas, blockade-running, and the impact of

war on civilians along the Tar Heel coast.

Recommended Reading: Ironclads and Columbiads: The Coast

(The Civil War in North Carolina) (456 pages). Description: Ironclads and Columbiads covers some of the most

important battles and campaigns in the state. In January 1862, Union forces began in earnest to occupy crucial points on the

North Carolina coast. Within six months, Union army and

naval forces effectively controlled coastal North Carolina from the Virginia

line south to present-day Morehead City.

Union setbacks in Virginia, however, led to the withdrawal of many federal soldiers from North Carolina, leaving only enough

Union troops to hold a few coastal strongholds—the vital ports and railroad junctions. The South during the Civil War,

moreover, hotly contested the North’s ability to maintain its grip on these key coastal strongholds.

Recommended Reading: The Civil War in the Carolinas

(Hardcover). Description: Dan Morrill relates the experience

of two quite different states bound together in the defense of the Confederacy, using letters, diaries, memoirs, and reports.

He shows how the innovative operations of the Union army and navy along the coast and

in the bays and rivers of the Carolinas affected the general course of the war as well as

the daily lives of all Carolinians. He demonstrates the "total war" for North

Carolina's vital coastal railroads and ports. In the latter part of the war, he describes

how Sherman's operation cut out the heart of the last stronghold

of the South. Continued below...

The author

offers fascinating sketches of major and minor personalities, including the new president and state governors, Generals Lee,

Beauregard, Pickett, Sherman, D.H. Hill, and Joseph E. Johnston. Rebels and abolitionists, pacifists and unionists, slaves

and freed men and women, all influential, all placed in their context with clear-eyed precision. If he were wielding a needle

instead of a pen, his tapestry would offer us a complete picture of a people at war. Midwest Book Review: The Civil War in the Carolinas by civil war expert and historian

Dan Morrill (History Department, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, and Director of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historical

Society) is a dramatically presented and extensively researched survey and analysis of the impact the American Civil War had

upon the states of North Carolina and South Carolina, and the people who called these states their home. A meticulous, scholarly,

and thoroughly engaging examination of the details of history and the sweeping change that the war wrought for everyone, The

Civil War In The Carolinas is a welcome and informative addition to American Civil War Studies reference collections.

Recommended

Reading: Gray Raiders of the Sea: How Eight Confederate Warships Destroyed the Union's High

Seas Commerce. Reader’s Review:

This subject is one of the most fascinating in the history of sea power, and the general public has needed a reliable single-volume

reference on it for some time. The story of the eight Confederate privateers and their attempt to bring Union trade to a halt

seems to break every rule of common sense. How could so few be so successful against so many? The United

States, after Great Britain,

had the most valuable and extensive import/export trade in the world by the middle of the 19th century. The British themselves

were worried since they were in danger of being surpassed in the same manner that their own sea traders had surpassed the

Dutch early in the 18th century. Continued below…

From its founding

in 1861, the Confederate States of America realized it had a huge problem since it lacked a navy.

It also saw that it couldn't build one, especially after the fall of its biggest port, New

Orleans, in 1862. The vast majority of shipbuilders and men with maritime skills lived north of the

Mason-Dixon Line, in the United States, and mostly in New

England. This put an incredible burden on the Confederate Secretary of the Navy, Stephen R. Mallory. When he saw

that most of the enemy navy was being used to blockade the thousands of miles of Confederate coasts, however, he saw an opportunity

for the use of privateers. Mallory sent Archibald Bulloch, a Georgian and the future maternal grandfather of Theodore Roosevelt,

to England to purchase British-made vessels

that the Confederacy could send out to prey on Union merchant ships. Bulloch's long experience with the sea enabled him to

buy good ships, including the vessels that became the most feared of the Confederate privateers - the Alabama,

the Florida, and the Shenandoah. Matthew Fontaine Maury

added the British-built Georgia, and the Confederacy itself launched the

Sumter, the Nashville, the Tallahassee,

and the Chickamauga - though these were generally not as effective

commerce raiders as the first four. This popular history details the history of the eight vessels in question, and gives detailed

biographical information on their captains, officers, and crews. The author relates the careers of Raphael Semmes, John Newland

Maffitt, Charles Manigault Morris, James Iredell Waddell, Charles W. Read, and others with great enthusiasm. "Gray Raiders"

is a great basic introduction to the privateers of the Confederacy. More than eighty black and white illustrations help the

reader to visualize their dramatic exploits, and an appendix lists all the captured vessels. I highly recommend it to everyone

interested in the Confederacy, and also to all naval and military history lovers.

|