|

President Zachary Taylor

"Old Rough and Ready"

(November 24, 1784 - July 9, 1850)

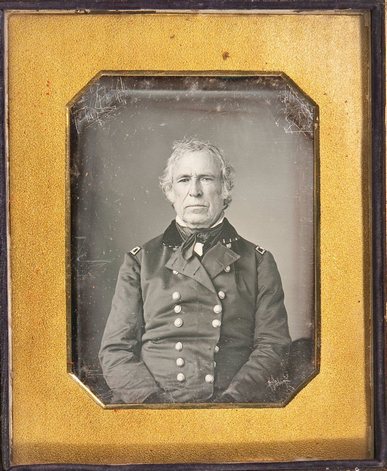

| President Zachary Taylor |

|

| President Zachary Taylor, 1849 |

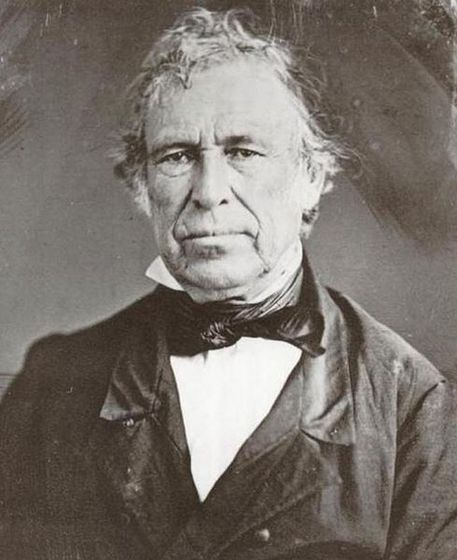

| Zachary Taylor |

|

| President Zachary Taylor, 1848. |

Twelfth President of the United States

1849-1850

Born: November 24, 1784, in Orange County, Virginia

Died: July 9, 1850 in Washington D.C. while in office. He got sick after eating cherries and milk at a July 4 celebration.

He was the second president to die in office.

(Right) Official White House portrait of President Zachary Taylor. Zachary

Taylor by Joseph Henry Bush, ca. 1848.

Summary

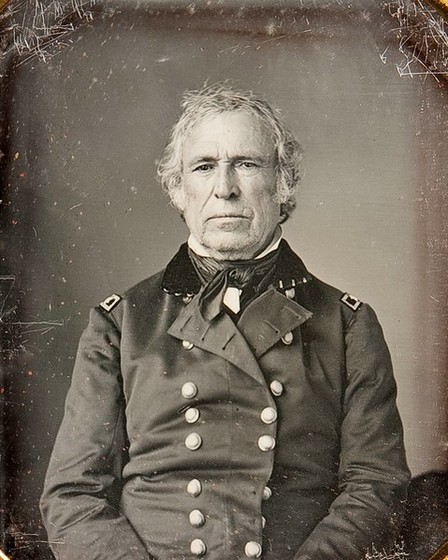

(Right) Daguerreotype of Gen. Zachary Taylor, taken at the White House,

by photographer Mathew Brady, in March 1849. Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was the 12th President

of the United States, serving from March 1849 until his death in July 1850. Before his presidency, Taylor was a career officer

in the United States Army, rising to the rank of major general. His status as a national hero as a result of his victories

in the Mexican-American War won him election to the White House despite his vague political beliefs. His top priority as president

was preserving the Union, but he died sixteen months into his term, before making any progress on the status of slavery, which

had been inflaming tensions in Congress. Taylor was born to a prominent family of planters who migrated westward from Virginia

to Kentucky in his youth. He was commissioned as an officer in the U.S. Army in 1808 and made a name for himself as a captain

in the War of 1812. He received numerous promotions establishing military forts along the Mississippi River and entered

the Black Hawk War as a colonel in 1832. His success in the Second Seminole War attracted national attention and earned him

the nickname and nom de guerre "Old Rough and Ready."

In 1845, as the annexation of Texas was underway, President James K. Polk

dispatched Taylor to the Rio Grande area in anticipation of a potential battle with Mexico over the disputed Texas–Mexico

border. The Mexican–American War broke out in May 1846, and Taylor led American troops to victory in a series of battles

culminating in the Battle of Palo Alto and the Battle of Monterrey. He became a national hero, and political clubs sprung

up to draw him into the upcoming 1848 presidential election.

The Whig Party convinced the reluctant Taylor to lead their ticket, despite

his unclear platform and lack of interest in politics. He won the election alongside U.S. Representative Millard Fillmore

of New York, defeating Democratic candidate Lewis Cass. As president, Taylor kept his distance from Congress and his cabinet,

even as partisan tensions threatened to divide the Union. Debate over the slave status of the large territories claimed in

the war led to threats of secession from Southerners. Despite being a Southerner and a slaveholder himself, Taylor did not

push for the expansion of slavery. To avoid the question, he urged settlers in New Mexico and California to bypass the territorial

stage and draft constitutions for statehood, setting the stage for the Compromise of 1850. Taylor died suddenly of a stomach-related

illness in July 1850, ensuring he would have little impact on the sectional divide that led to civil war a decade later.

Family

Taylor was born on November 24, 1784, on a plantation in Orange County,

Virginia, to a prominent family of planters of English ancestry. He is inconclusively believed to have been born at the home

of his maternal grandfather, Hare Forest Farm. He was the third of five surviving sons in his family (a sixth died in infancy)

and had three younger sisters. His mother was Sarah Dabney (Strother) Taylor. His father, Richard Taylor, had served as a

lieutenant colonel in the American Revolution. Taylor was a descendant of Elder William Brewster, the Pilgrim colonist leader

of the Plymouth Colony, a Mayflower immigrant, and one of the signers of the Mayflower Compact; and Isaac Allerton Jr., a

colonial merchant and colonel who was the son of Mayflower Pilgrim Isaac Allerton and Fear Brewster. Taylor's second cousin

through that line was James Madison, the fourth president.

Leaving exhausted lands, his family joined the westward migration out of

Virginia and settled near what developed as Louisville, Kentucky, on the Ohio River. Taylor grew up in a small woodland cabin

before his family moved to a brick house with increased prosperity. The rapid growth of Louisville was a boon for Taylor's

father, who came to own 10,000 acres throughout Kentucky by the start of the 19th century; he held 26 slaves to cultivate

the most developed portion of his holdings. There were no formal schools on the Kentucky frontier, and Taylor had a sporadic

formal education. A schoolmaster recalled Taylor as a quick learner. His early letters show a weak grasp of spelling and grammar,

and his handwriting was later described as "that of a near illiterate."

In June 1810, Taylor married Margaret Mackall Smith, whom he had met the

previous autumn in Louisville. "Peggy" Smith came from a prominent family of Maryland planters; she was the daughter of Major

Walter Smith, who had served in the Revolutionary War. The couple had six children:

Ann Margaret Mackall Taylor (1811–1875) married Robert C. Wood,

a U.S. Army surgeon she had met while living Fort Snelling, in 1829.

Sarah Knox Taylor (1814–1835) married Jefferson

Davis (future Confederate President) in 1835, whom she had met through her father at the end of the Black Hawk War; she

died at 21 of malaria in St. Francisville, Louisiana, shortly after her marriage.

Octavia Pannill Taylor (1816–1820).

Margaret

Smith Taylor (1819–1820) died in infancy along with Octavia when the Taylor family was stricken with a "bilious fever."

Mary

Elizabeth Taylor (1824–1909), married William Wallace Smith Bliss (died 1853) in 1848.

Richard "Dick" Taylor (1826–1879),

Confederate Army general during the Civil War.

| President Zachary Taylor, 1849. |

|

| President Zachary Taylor and administration in 1849 |

(About) President Taylor and his Cabinet. From left to right: William B.

Preston, Thomas Ewing, John M. Clayton, Zachary Taylor, William M. Meredith, George W. Crawford, Jacob Collamer and Reverdy

Johnson, (1849). President Zachary Taylor's cabinet, 1849 daguerreotype by Mathew Brady, Library of Congress.

Politics

Northerners and Southerners disputed sharply whether the territories wrested from Mexico should

be opened to slavery, and some Southerners even threatened secession. Standing firm, Zachary Taylor was prepared to hold the Union together by armed force rather than by compromise.

Born in Virginia in 1784, he was taken as an infant to Kentucky and raised on a plantation. He was a career

officer in the Army, but his talk was most often of cotton raising. His home was in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and he owned a

plantation in Mississippi. But Taylor did not defend slavery or Southern sectionalism; 40 years in the Army made him a strong nationalist.

Zachary Taylor was 2nd cousin to President James Madison and, ironically, 4th cousin, once removed, to General Robert E. Lee, and father-in-law to (future) Confederate President Jefferson

Davis. Taylor's daughter Sarah Knox had married Davis, but not at the approval of her father.

Taylor spent a quarter of a century policing the frontiers against Indians. In the Mexican War, he won major victories at Monterrey and Buena Vista. Although Zachary Taylor would return to the United States as

a hero, he would be known as the soldier's soldier, for he conversed with lowly privates, respected each soldier, and

condescended to no one.

| President Zachary Taylor |

|

| President Zachary Taylor, ca. 1850. |

| President Zachary Taylor |

|

| President Zachary Taylor, ca. 1844. |

|

| President Zachary Taylor signature |

| President Zachary Taylor |

|

| Taylor's mausoleum at the Zachary Taylor National Cemetery in Louisville, Kentucky. |

President Polk, disturbed by General Taylor's informal habits of command and perhaps his Whiggery as well,

kept him in northern Mexico and sent an expedition under Gen. Winfield Scott to capture Mexico City. Taylor, incensed, thought that "the battle of Buena Vista opened the road to the city of Mexico

and the halls of Montezuma that others might revel in them."

"Old Rough and Ready's" homespun ways were political assets. His long military record would appeal to northerners;

his ownership of 100 slaves would lure southern votes. He had not committed himself on troublesome issues. The Whigs nominated

him to run against the Democratic candidate, Lewis Cass, who favored letting the residents of territories decide for themselves

whether they wanted slavery.

In protest against Taylor the slaveholder and Cass the advocate of "squatter sovereignty," northerners who

opposed extension of slavery into territories formed a Free Soil Party (Free Soilers and the Free Soil Party) and nominated Martin Van Buren. In a close election, the Free Soilers pulled enough votes away from Cass to elect Taylor.

Although Taylor had subscribed to Whig principles of legislative leadership, he was not inclined to be a puppet

of Whig leaders in Congress. He acted at times as though he were above parties and politics. As disheveled as always, Taylor

tried to run his administration in the same rule-of-thumb fashion with which he had fought Indians.

Traditionally, people could decide whether they wanted slavery when they drew up new state constitutions.

Therefore, to end the dispute over slavery in new areas, Taylor urged settlers in New Mexico and California to draft constitutions

and apply for statehood, bypassing the territorial stage.

Southerners were furious, since neither state constitution was likely to permit slavery; Members of Congress

were dismayed, since they felt the President was usurping their policy-making prerogatives. In addition, Taylor's solution

ignored several acute side issues: the northern dislike of the slave market operating in the District of Columbia; and the

southern demands for a more stringent fugitive slave law.

In February 1850, President Taylor had held a stormy conference with southern leaders who threatened secession.

He told them that if necessary to enforce the laws, he personally would lead the Army. Persons "taken in rebellion against

the Union, he would hang ... with less reluctance than he had hanged deserters and spies in Mexico." He never wavered.

Then events took an unexpected turn. After participating in ceremonies at the Washington Monument on a blistering

July 4, Taylor fell ill; within five days he was dead. After his death, the forces of compromise triumphed, but the war Taylor

had been willing to face came 11 years later. In it, his only son Richard served as a general in the Confederate Army. General

Nathan Bedford Forrest commented that if the South had more soldiers like General Richard Taylor, "we would have

licked the Yankees long ago."

| President Zachary Taylor history |

|

| (Left) Zachary Taylor; (Right) Margaret Smith. View through doors of mausoleum. |

Death

On July 4, 1850, Taylor reportedly consumed raw fruit, probably cherries,

and iced milk after attending holiday celebrations and a fund-raising event at the Washington Monument, which was then under

construction. Over the course of several days, he became severely ill with an unknown digestive ailment. His doctor "diagnosed

the illness as cholera morbus, a flexible mid–nineteenth century term for intestinal ailments as diverse as diarrhea

and dysentery but not related to Asiatic cholera," the latter being a widespread epidemic at the time of Taylor's death. The

identity and source of Taylor's illness are the subject of historical speculation (see below), although it is known that several

of his cabinet members had come down with a similar illness.

Fever ensued and Taylor's chance of recovery was small. On July 8, Taylor

remarked to a medical attendant:

"I should not be surprised if this were to terminate in my death. I

did not expect to encounter what has beset me since my elevation to the Presidency. God knows I have endeavored to fulfill

what I conceived to be an honest duty. But I have been mistaken. My motives have been misconstrued, and my feelings most grossly

outraged."

Despite treatment, Taylor died at 10:35 p.m. on July 9, 1850. He was 65

years old.

Taylor was interred in the Public Vault of the Congressional Cemetery

in Washington, D.C. from July 13, 1850 to October 25, 1850. (It was built in 1835 to hold remains of notables until either

the grave site could be prepared or transportation arranged to another city.) His body was transported to the Taylor Family

plot where his parents were buried, on the old Taylor homestead plantation known as 'Springfield' in Louisville, Kentucky.

In 1883, the Commonwealth of Kentucky placed a fifty-foot monument in his

honor near his grave; it is topped by a life-sized statue of Taylor. By the 1920s, the Taylor family initiated the effort

to turn the Taylor burial grounds into a national cemetery. The Commonwealth of Kentucky donated two pieces of land for the

project, turning the half-acre Taylor family cemetery into 16 acres. On May 6, 1926, the remains of Taylor and his wife (who

died in 1852) were moved to the newly constructed Taylor mausoleum nearby. (It was made of limestone with a granite base,

with a marble interior.) The cemetery property has been designated as the Zachary Taylor National Cemetery.

Conspiracy Theories

Almost immediately after his death, rumors began to circulate that Taylor

was poisoned by pro-slavery Southerners, and similar theories persisted into the twentieth century. In 1978, Hamilton Smith

based his assassination theory on the timing of drugs, the lack of confirmed cholera outbreaks, and other material. In the

late 1980s, Clara Rising, a former professor at University of Florida, persuaded Taylor's closest living relative to agree

to an exhumation so that his remains could be tested. The remains were exhumed and transported to the Office of the Kentucky

Chief Medical Examiner on June 17, 1991. Samples of hair, fingernail, and other tissues were removed, and radiological studies

were conducted. The remains were returned to the cemetery and reinterred, with appropriate honors, in the mausoleum. Neutron

activation analysis conducted at Oak Ridge National Laboratory revealed no evidence of poisoning, as arsenic levels were too

low. The analysis concluded Taylor had contracted "cholera morbus, or acute gastroenteritis", as Washington had open sewers,

and his food or drink may have been contaminated. Any potential for recovery was overwhelmed by his doctors, who treated him

with "ipecac, calomel, opium and quinine (at 40 grains a whack), and bled and blistered him too." Political scientist Michael

Parenti questions the traditional explanation for Taylor's death, and, relying on interviews and reports by forensic pathologists,

argues that the procedure used to test for arsenic poisoning was fundamentally flawed. A 2010 review concludes: "there is

no definitive proof that Taylor was assassinated, nor would it appear that there is definitive proof that he was not."

Sources: whitehouse.gov; National Archives and Records Administration; U.S. State Department; National Park

Service.

Recommended Reading:

Zachary Taylor: The 12th President, 1849-1850 (The American Presidents) (Hardcover).

Description: The

rough-hewn general who rose to the nation’s highest office, and whose presidency witnessed the first political skirmishes

that would lead to the Civil War. Zachary Taylor was a soldier’s soldier, a man who lived up to his nickname, “Old

Rough and Ready.” Having risen through the ranks of the U.S. Army, he achieved his greatest success in the Mexican War,

propelling him to the nation’s highest office in the election of 1848. He was the first man to have been elected president

without having held a lower political office. John S. D. Eisenhower, the son of another soldier-president, shows

how Taylor rose to the presidency, where he confronted the

most contentious political issue of his age: slavery. Continued below...

The political

storm reached a crescendo in 1849, when California, newly populated after the Gold Rush, applied for statehood with an anti-slavery constitution,

an event that upset the delicate balance of slave and free states

and pushed both sides to the brink. As the acrimonious debate intensified, Taylor stood his

ground in favor of California’s admission—despite

being a slaveholder himself—but in July 1850 he unexpectedly took ill, and within a week he was dead. His truncated

presidency had exposed the fateful rift that would soon tear the country apart.

Related Reading:

Recommended Reading: Zachary Taylor: Soldier, Planter, Statesman of the Old Southwest. Description: Zachary Taylor was one of the most unlikely men to ever serve as president of

the United States. Self-educated, an average

and conservative military leader, considered by many to be less than intellectual, but General Zachary Taylor, affectionately

referred to as the soldier’s soldier, was thrust into the limelight because of his success in the Mexican War. Although

a southerner, Taylor opposed the extension of slavery and threatened dire consequences to secessionists. (Ironically, his

son, Richard Taylor, became one of the South’s greatest Civil War generals.) Continued below...

He

died unexpectedly after serving only sixteen months as president. His death occurred just as he was reorganizing his administration

and attempting a recasting of the Whig Party. Mr. Bauer does a good job of describing the effect that Zachary Taylor had on

the nation as well as that “personal side” of the soldier’s soldier.

Recommended Reading: President Zachary Taylor: The Hero President (First Men, America's Presidents) (Hardcover). Description: Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784

- July 9, 1850) was an American military leader and the twelfth President of the United States. Taylor had a 40-year military career

in the U.S. Army, serving in the War of 1812, Black Hawk War, and Second Seminole War before achieving fame while leading

U.S. troops to victory at several critical

battles of the Mexican-American War. Continued below…

Taylor's

short Presidency was shadowed by the issue then dominating all aspects of American national affairs - that of slavery. However,

the immediate issue was the admission of New Mexico and California

as states. Taylor confounded his Southern supporters, who

had assumed that since the President owned slaves, he would support the pro-slavery position and refuse entry into the union

to two states settled by Northerners and likely to be anti-slavery. Taylor

recommended that the two territories develop their own constitutions and then request admission based on those constitutions.

When Southern states threatened secession he warned them that he would use all his resources as commander-in- chief to preserve

the union. He stated that if they seceded he would track them down like he had the Mexicans, and handle them in the same manner

that he had deserters. Taylor's brief term in the White House

also featured the still on-going question of balancing power between the Congress and the presidency.

Recommended Reading:

Letters Of Zachary Taylor From The Battlefields Of The Mexican War (1908).

Review: If you are interested in this influential episode of US

history, this book conveys it straight from the proverbial horse’s mouth. In contrast with often one-sided accounts

like President Polk's and others’ memoirs, this book displays the human side of the invasion of Mexico. General Taylor reveals that he was conflicted in many

standpoints ranging from ethical to military and political. Although he understood that it was his duty to serve his country

and fight in a war against the weaker neighbor, Mexico, he shows us an

emotional and personal side rarely seen in America’s

top brass.

Recommended

Reading: A People's History of the United States:

1492 to Present. Review:

Consistently lauded for its lively, readable prose, this revised and updated edition of A

People's History of the United States turns traditional textbook history on its head. Howard Zinn infuses the

often-submerged voices of blacks, women, American Indians, war resisters, and poor laborers of all nationalities into this

thorough narrative that spans American history from Christopher Columbus's arrival to an afterword on the Clinton presidency. Addressing his trademark reversals of perspective, Zinn--a teacher, historian,

and social activist for more than 20 years—explains: "My point is not that we must, in telling history, accuse, judge,

condemn Columbus in absentia. It is too late for that; it

would be a useless scholarly exercise in morality. Continued below…

But the easy

acceptance of atrocities as a deplorable but necessary price to pay for progress (Hiroshima and Vietnam, to save Western

civilization; Kronstadt and Hungary, to

save socialism; nuclear proliferation, to save us all)--that is still with us. One reason these atrocities are still with

us is that we have learned to bury them in a mass of other facts, as radioactive wastes are buried in containers in the earth."

If your last experience of American history was brought

to you by junior high school textbooks--or even if you're a specialist--get ready for the other side of stories you may not

even have heard. With its vivid descriptions of rarely noted events, A People's History of the United

States is required reading for anyone who wants to take a fresh look at the rich, rocky history of America. "Thought-provoking,

controversial, and never dull..."

|