|

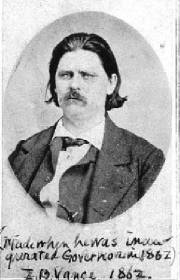

| Governor Zeb Vance |

|

| Governor Zebulon Vance |

Governor Zeb Vance

THE DUTIES OF DEFEAT.

AN ADDRESS

DELIVERED BEFORE THE

Two Literary Societies

OF THE

UNIVERSITY

OF NORTH CAROLINA,

June 7th, 1866,

BY

EX-GOV. ZEBULON BAIRD VANCE.

RALEIGH:

WILLIAM B. SMITH & COMPANY

1866.

Page 3

CORRESPONDENCE.

UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA,

DIALECTIC HALL, June 8, 1866.

HON. Z. B. VANCE:

Dear Sir--In behalf of the Dialectic Society, the undersigned have

been instructed to request for publication a copy of the speech delivered by you on the 7th instant, before the Literary Societies

of the University of North Carolina.

They are influenced by the desire to make public the wise and states-manlike

views it contains concerning the relations of the Southern people and the duties in consequence incumbent upon them.

In making this request they believe they have the concurrence of all who

heard it.

We have the honor to be,

Very respectfully, &c.,

T. M. ARGO,

A. PHILLIPS,

G. W. GRAHAM,

Committee.

CHARLOTTE, N. C., June 16, 1866.

Gentlemen:--Your note has been received, in which you request a

copy of the speech recently delivered by me before the two Societies of the University, for publication.

The time allowed me for its preparation, after the acceptance of your invitation,

was so limited that I feel unwilling to have it published.--But deferring to your complimentary opinion, I cannot refuse to

comply with your request. The manuscript is therefore placed at your disposal.

Thanking you, and those whom you represent, most sincerely for the honor

you have done me,

I am, gentlemen,

Very truly yours,

Z. B. VANCE.

To Messrs. T. M. ARGO,

A. PHILLIPS,

G. W. GRAHAM.

Committee.

Page 5

THE DUTIES OF DEFEAT.

Gentlemen of the Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies:

As the traveller, who, during his absence, has learned that a great fire

has swept over his native city, welcomes with the keenest rapture the first glance of his own home, which he trembles at the

thought of finding in the ashes of the general ruin, so should we rejoice, to behold our honored University surviving

the wreck of so much that we loved and revered.--Though staggering under the blows of adversity, I am most happy to see for

myself, this day, so goodly a display of her ancient life and energy. May she soon attain to that full measure of prosperity

and usefulness, which has heretofore rendered her the pride and chiefest ornament of North Carolina!

Since the first keel of an European vessel grated upon the sands of the

new world, and the first axe was lifted against the vast forest which covered it as with a crown of glory, the lines could

not have fallen to the educated young men of our State in a more interesting or important era. We stand to-day amidst the

stranded fragments and floating timbers of the greatest civil war in history. Astounded at the mighty results we are as yet

unable to comprehend them. Indeed, the profound significance of their full philosophical import, can scarcely be gathered

by this generation. For we are not yet at the end of the Revolution as is popularly supposed, but are only, as we trust, at

the end of armed violence. The changes, which constituted the real objects of the Revolution, began with us, only when the

last Confederate soldier, by laying down his arms, removed that last obstacle to their approach.

Revolutions are not now what they were. They partake in the manner of their

accomplishment of the spirit of the age; and are hurried forward by the same impulses of science and discovery which have

so accelerated the material affairs of the world. How suddenly all of our well settled theories in regard to the relative

powers and duties of the States and the Federal Government, have been overthrown, and the whole system changed, it is astonishing

to contemplate. The almost immediate

Page 6

emancipation of three million five hundred thousand slaves, without one moment's preparation, of either themselves or their

masters, for the great change, is equally unprecedented, and brings us with breathless haste, face to face, with some of the

most startling and dangerous questions of the age. But when we remember some of the chief strides of physical science in the

past few years, our wonder will diminish. It was but thirty-six years ago that the first railroad was built, and the first

steam engine mounted upon his iron track. Already there are in existence fifty-six thousand miles, threading and permeating

the civilized world; more than enough, if stretched out in straight and parallel lines, to bind an iron girdle twice around

the solid framework of the globe! That narrow highway of the lightning--now become the guide and friend of the engine,--if

stretched by its side, would enable one to hurl his words around the entire earth, returning to him who spoke them almost

ere they had sounded upon his own ear! By these and similar wondrous agencies, during the recent war, two stupendous corps

d'armée, who were facing each other on the banks of the Potomac, would steal in their picket lines under cover of darkness,

and, rushing away with all their trains and animals, and munitions of war, would, within a few short hours, be hurled against

each other again in deadly strife on some distant field, half across the continent! Change, therefore, not only cometh upon

us, but cometh with speed and with power.

Perhaps in modern annals there will scarcely be found a parallel to the

complete ruin and impoverishment of the people of the Southern States. Absolute annihilation of a great community by armed

violence is deemed scarcely possible in modern times, though instances are not wanting among the ancients, before a humane

code of international law had interposed to protect the weak against the strong, and mitigate the horrors of war. The most

wonderful example was that of Carthage.--Though her walls were twenty-seven miles in circumference, and she could keep five

hundred elephants for the public amusements; though she could send three hundred thousand soldiers to the invasion of Greece,

while Rome was engaged in a death struggle with a petty town only twelve miles distant from her walls; though the waters of

every sea were white with her sails and the shores of every known land were visited by her merchants,

Page 7

or planted with her colonies; yet the iron hand of her rival smote her so utterly into the dust that there is not a vestige

left! Not a monument is standing; no literature, no relic of her laws, her language or her blood remains. The very site

of this great city is of the doubtful knowledge of the antiquary. Such barbarous inflictions of a barbarous age we have indeed

escaped, but changes greater than the dreams of the wildest, and ruin, social and political, fearfully deep, has been our

hapless lot.--A glance at these things, for the purpose of attempting to deduce the outline of the changed duties which devolve

upon us, will suffice to-day.

What with the value of our slaves, the injury inflicted upon real property,

the destruction of personal, the depreciation or annihilation of all manner of stocks and securities, together with the sums

expended in the maintenance of the war, make our material losses alone, all told, in the estimation of the most prudent, equal

to five thousand million dollars! And of that highest and noblest property of a State--her citizens--full two hundred and

fifty thousand of our bravest and best have perished by the casualties of war alone! The filling up of this fearful outline,

with the revolting minutię of individual suffering, or the estimation of the moral losses we have incurred, is a task I have

neither heart nor time for attempting. The whole scene reminds one of the portraiture of Rome, drawn by one of the panegyrists,

when addressing the Emperor Theodosius:--"Thou, Rome, that having once suffered by the madness of Cinna, and of the cruel

Marius raging from banishment, and of Sylla that won his wreath of prosperity from thy disasters, and of Cęsar compassionate

to the dead, didst shudder at every blast of the trumpet filled by the breath of civil commotion.--Thou, that beside the wreck

of thy soldiery perishing on either side, didst bewail amongst thy spectacles of domestic woe, the luminaries of thy Senate

extinguished, the heads of thy consuls fixed upon a halberd, weeping for ages over thy slaughtered Catos, thy headless Ciceros

and unburied Pompeys;--to whom the party madness of thy own children had wrought in every age heavier woe than the Carthaginians

thundering at thy gates, or the Gaul admitted within thy walls; on whom Emathia more fatal than the day of Allia--Collina

more dismal than Cannę--had inflicted such deep memorials of wounds that,

Page 8

from bitter experience of thy own valor no enemy was to thee so formidable as thyself." Would that, with the spirit of

prophecy, I could add the remainder of the quotation: "Now first in thy long annals, thou didst rest from a civil war in such

a peace, that righteously and with maternal tenderness, thou mightest claim for it the honors of a

civic triumph!"

Upon our own beloved State a full share of these common calamities has

fallen. Nor does it relieve them of their crushing weight to remember the deep hostility of her people to the policy which

inaugurated them. Quiet, conservative, law-abiding, as her people have ever been,--though jealous of their rights and honor,

and ready at any moment to perish for them,--yet slow to violate compacts, they have never ceased to prefer exhausting all

civil remedies for the redress of public grievances rather than evoke the terrible and uncertain arbitrament of revolution.

Steady in the exercise of this resolution, she was forced, the very last, into a conflict which she was the very first in

maintaining. The sufferings of our people have, indeed, been fearfully commensurate with their honesty and their courage.

With her homesteads burned to ashes, with fields desolated, with thousands of her noblest and bravest children sleeping in

beds of slaughter; innumerable orphans, widows, and helpless persons, reduced to beggary and deprived of their natural protectors;

her corporations bankrupt and her own credit gone; her public charities overthrown, her educational fund utterly lost, her

land filled from end to end with her maimed and mutilated soldiers; denied all representation in the public councils, her

heart-broken and wretched people are not only oppressed with the weight of their own indebtedness, but are crushed into the

very dust by taxation for the mighty debt incurred as the cost of their own subjugation! The very race of beasts of burthen,--by

which alone we could extort bread from the half-tilled earth,--was, at the close of hostilities, almost destroyed; leaving

us destitute of even the means of labor! Such a picture of suffering would seem sufficient to sate a generous enemy, and should

move the deepest depths in the bosoms of her loving sons. Truly might they, as during the ever memorable year 1865 they beheld

"all this wealth and glory turnd to dust and tears," have fancied that they could hear

"A cry of nations o'er her sunken halls,

Page 9

A loud lament along the sweeping sea."

It was enough to cause her despairing children to re-echo the plaintive

wail of the poet over fallen Venice:

"There is no hope for nations. Search the page

Of many thousand years,--the daily scene,

The flood and ebb of each recurring age,

The everlasting to be which hath been,

Hath taught us naught or little,--still we lean

On things that rot beneath our weight, and wear

Our strength away in wrestling with the air."

There was indeed a cry and a lament, through all her borders. From her

Alpine heights to her tidal sands, from her plains and valleys and all her habitations, the wail went up. The dismal cypress,

garlanded with funereal moss, became fit emblem of her woe; and her sombre pines, moaning in the breeze, sang requiems solemn,

as for the dead. And though nature was still kindly, and invited us to forget our sorrow; though the sun still warmed and

cherished the earth; though the early and the latter rains still descended according to the Promise, clothing the fields with

verdure, and causing the tender herb to put forth; and though the mocking bird--sweetest of our warblers--embowered within

the shadows of his leafy home, poured forth his glorious song, "every note that we loved awaking," yet no joyous response

stirred our bosoms. It seemed, indeed, that despair had claimed us for her own. We felt that it was demanded of us to sing

a song in a strange land, and we could but hang our harps upon the willows of our own native rivers--famous now with the rich

memories of our children's blood--and weep when we remembered the pleasant places from which we had fallen. It was in truth

a prospect to appal the stoutest hearted; and many of our aged and infirm, who had bravely borne all

the sufferings of a four years war, have sunk down like the oak which, having withstood the storm, yet falls in the ensuing

calm, and died, "rejoicing exceedingly and being glad that they could find the grave."

Such are the changes through which we have passed and are still passing.

Such is the condition, physical and social, of your country at the moment when you are to enter upon the earnest duties of

life. You will probably agree with me in thinking that the time is an important one, and that the duties before young men

of education and patriotism differ widely from, and far exceed in weighty responsibility, those which have devolved on any

of your predecessors.

Page 10

It will not be improper to glance at some of the peculiar fields where

your energies, as well as your kindly charities, may be most beneficially expended. The task of uplifting and regenerating

our fallen country, indeed, belongs to us all; but it will devolve more especially upon you. Neither spent, nor broken down,

by the fierce conflicts and deadly disappointments of the past, your fresh spirits are not only endowed with the vigor necessary

to successful action, but they can more easily bend to the Procrustean bed of circumstances, which is spread for the repose

of a conquered people,--wherein lies, now, and at all times, the true secret of statesmanship.

The work is not near so hopeless as it would seem at first, and it is noble

and glorious beyond anything that ever fired the ambition of youth. Though the destruction is so wide-spread and through,

it should be remembered that there is nothing which can exceed the recuperative powers of nature when aided by the industry

of man. These gaping wounds in our country's bosom are to be healed, these enormous losses of our wealth are to be repaired,

these wasted fields are to be restored to the glorious verdure of peaceful abundance--from the ashes of the homes which once

sheltered us must arise the beams and rafters of homes still as beautiful and as happy. The blackened chimneys must no longer

stand, grim and solitary, on the landscape, surrounded by rank and profitless weeds, the sorrowful mile-marks of the sweep

of desolation as it marched, devouring our substance, but must be made to send up again, from mansion roofs, the cheerful

columns of smoke which once bespoke plenty and repose, and to glow again with winter's blaze of domestic peace and sacred

hospitality. All the bloody footprints of ruthless war must be erased by the hand of intelligent industry.

Looking despairingly at the condition of things, the country turns toward

her young men, and calls to them to lead the way in preaching and practicing hope. You are required, above all things,

to teach our people to look up from the crumbling ashes and prostrate columns of their present ruin, to the majestic proportions

and surpassing grandeur of that temple which may yet be built by the hand which labors, the mind which conceives, and the

great soul which faints not.

An officer leading his men into battle, himself going first and charging

home upon the enemy, with the high and lofty daring

Page 11

of a hero, rallying his troops when they waver, cheering when they advance, applauding the brave and sustaining the fainthearted,

bearing aloft the colors of his command, and struggling with all the strength and spirit of manhood, resolving to conquer

or to perish, is esteemed one of the noblest exhibitions of which man is capable. We thrill and burn, as we read the glowing

story, and exhaust the language of praise, in extolling his virtues. But not less glorious, not less worthy the commendations

of his countrymen, is he who in an hour like this bravely submits to fate; and scorning alike the promptings of despair, and

the unmanly refuge of expatriation, rushes to the rescue of his perishing country, inspires his fellow citizens with hope,

cheers the disconsolate, arouses the sluggish, lifts up the helpless and the feeble, and by voice and example, in every possible

way, urges forward all to the blessed and bloodless and crowning victories of peace. It is a noble thing to die for one's

country: it is a higher and a nobler thing to live for it.

The best test of the best heroism now, is a cheerful and loyalsubmission

to the powers and events established by our defeat, and a ready obedience to the Constitution and laws of our country. Being

denied the immortal distinction of dying for your country, as did your fathers and your eldest brothers, you may yet rival

their glory, by living for it, if you will live wisely, earnestly and well. The greatest campaign, for which soldiers

ever buckled on armor, is now before you. The drum beats, and the bugle sounds to arms, to repel invading poverty and destitution,

which have seized our strongholds and are waging war, cruel and ruthless, upon our women and children. The teeming earth is

blockaded by the terrible lassitude of exhaustion, and we are required, through toil and tribulation, to retake, as by storm,

that prosperity and happiness, which were once our own, and to plant our banners firmly upon their everlasting ramparts, amid

the plaudits of a redeemed and regenerated people. The noblest soldier, now, is he that, with axe and plough, pitches

his tent against the waste places of his fire-blasted home, and swears that from its ruins there shall arise another like

unto it; and that from its barren fields, there shall come again the gladdening sheen of dew-gemmed meadows, in the rising,

and the golden waves of ripening harvests, in the setting sun! This is a besieging of fate itself; a hand to hand struggle

with the stern columns of calamity

Page 12

and despair. But the God of nature hath promised that it shall not fail, when courage, faith and industry sustain the assailant;

and this victory won, without one drop of human blood, unstained by a single tear, imparting and receiving blessings on every

hand, will be such as the wise and good of all the earth may applaud, and over which even the angels might unite in rejoicing.

Now, from the earth, directly or indirectly, comes all the wealth of man,

whether it be in flocks upon the hills, in palaces within the city, or in ships upon the sea. In this prolific and never failing

source alone, must be laid the foundations of our regeneration, and the plow is the great instrument with which it is to be

effected. The oldest born, the simplest and most beneficent of inventions, the father and king of all the implements of man,

upon it depends all of agriculture, of manufactures, of commerce and of civilization. Remembering this, it will be your first

and last great duty, whether as legislators or as private citizens, to encourage, foster and protect labor upon the soil:

being assured when it prospers that all other desirable things shall be added.

During the course of the recent war it was often a subject of remark that

each side was grievously deceived in its estimate of the other. And especially was it a favorite opinion at the North, that

we of the South were not capable of sustaining for a protracted period the rigors of war. It was said that our climate, and

more especially the system of slavery, had unmanned us, and sunk us into effeminacy, and rendered us totally unfit to grapple

with the hardier and more robust races of the North.--How they were undeceived by four years of the most desperate strife

against overwhelming numbers and resources, it is the province of history to tell. Nor need we fear to let them write

that history; for a denial of the full and glorious import of our deeds would be a confession of their own shame and inferiority.

It will be our duty now, in better ways, and under happier auspices, still further to undeceive them, by the vigor and energy

with which we shall clear away the wreck of our fallen fortunes, adapt ourselves to circumstances under changed institutions

and new systems of labor, and the rapidity with which we shall travel in those ways which lead to the rebuilding and adorning

a State. Nor will it admit of a doubt that the same courage, constancy and skill, which led our slender battalions through

so many

Page 13

pitched fields of glory, will, when directed into the peaceful channels of national prosperity and quickened by the sharp

lessons of adversity, be sufficient to place the Southern States of the American Union side by side with the richest and the

mightiest.

Deserving also of your earnest attention is that moral ruin--scarcely less

extensive than the physical--which dogs the footsteps of revolution. No classes of our society have altogether escaped it,

whilst in some its ravages have been fearful. The peculiar counteracting influences--those of schools and schoolmasters--the

general poverty of the country has well nigh destroyed. The almost total loss of the very considerable fund set apart by the

wisdom of our Legislators in happier times for the education of the poor children of the State, and the consequent abandonment

of our system of Common Schools, are by no means to be reckoned among the least of our many misfortunes. To the thousands

of children, whose parents were heretofore unable to educate them, are now added other thousands reduced to a worse condition

by the results of the war. Their situation forms a subject of the most serious magnitude, and imposes additional obligations

upon all, who, like you, have been favored with the means and opportunity of education. But among all the sacred duties which

will devolve on you as citizens and patriots, there are some more sacred still than others; and one of these is the looking

after, and caring for, the orphans of those who perished in your defence and mine. Numbers of them are destitute not only

of the means of education, but of subsistence itself. Without friends or protectors, they will wander into ways of wickedness

and ruin. It has already been my painful fortune, to witness an instance of such an one brought into the courts of justice,

charged with crimes committed under the influence of want, and in the absence of a father's teachings. But that father was

sleeping far away in a rude soldier's grave in the wilderness of the Chickahominy, and his orphan boy, without a parent, a

protector, or a friend in the world, lone and homeless, had wandered among strangers and been tempted into crime. I visited

him in prison, where without a coat, without shoes or hat, and his few remaining garments displaying his pale and delicate

frame, he told me his simple and piteous story. His tender years and helpless condition appealed so strongly to the court

that the penalties of the

Page 14

law were not inflicted on him. A kind gentleman came forward, agreed to give him a home and became bound for his better

behavior: and being admonished to go and sin no more, he was led away. But my heart bled within me, when I remembered that

he was only one of thousands whose fortune was equally hard, and that he had thus lost home, and father, and an honest life,

for you and for me! Oh! my friends, may God do so to you, and more also, if you ever turn your backs upon an orphan

child of one who perished in your defence! Their blood was shed, whether wisely or unwisely, in your behalf; let it appeal

to you for their naked and helpless children, from the fields of slaughter where they spilled it, and woe be unto you, if

it appeals in vain! "The Lord deal kindly with you, as ye have dealt with the dead."

Nor do our duties to these brave men cease with their children. There is

a debt which neither test oaths nor Congressional amendments have forbidden us to pay. We owe to the dead what it is possible

to do for their remains and their memories, and no charge of faithlessness to our own obligations, it seems to me, should

stand between us and its discharge.

"Their

bones are scattered far and wide,

By

mount, by stream and sea,"

and it is not for the purpose of eulogizing the cause, for which they perished, (for that is already in the hands

of history,) that we would gather them up for decent sepulture, and perpetuate their memories by tablets

of stone. It is simply to testify our love for our own blood, and our grateful admiration of the virtue and patriotism, and

unavailing courage, which laid them low. From that fatal wall of Gettysburg to the banks of the Rio Grande, two thousand miles

of travel are marked by the Golgothas of our kindred. In nameless valleys, on rugged mountains, in wild and solitary swamps,

the noblest, and the bravest, and the highest of Southern manhood--children of the Cavalier and the Huguenot--sleep in shallow

and unknown graves, or moulder upon the soil like the beasts that perish.--The lawgiver and the plowman, the poet and the

cart boy, the accomplished scholar and the rude father of the hamlet, rest side by side awaiting the final trump, and many

a mother that bore him knows not of his lowly bed, nor can cast one flower upon the grave of her lost boy. And yet the nations

listened to the roar of that boy's musket, and watched, with heart aglow

Page 15

and blood on fire, as he strove to erect the "arch of empire" through the belching flames and glittering bayonets of many

a battlemented height! Lustre and glory--everything but success--he shed abundantly upon his country.

"The silent pillar, lone and gray,

Claims kindred with his sacred clay;

The meanest rill, the mightiest river,

Rolls mingling with his fame forever."

When the civilized world has rung with the praises of these men, and even

the generous of their foes have not withheld the homage ever due to valor and to virtue, certainly we may be pardoned for

seeking to do this poor honor to our own.

"If

I, a Northern wanderer, weep for thee,

What

should thy sons do?"

The very least that we can do, is to bring their remains home and bury

them with decency and in silence. No monuments of victory are for us, no national jubilee can we celebrate, no songs of triumph

can our maidens sing, or garlands of glory weave; there is no welcoming of returning conquerors, nor erecting of triumphal

arches for us to console us for our great suffering. We are all alone with our great defeat and that heavy sorrow, which,

"never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting," in our households; and all that we have left for our comfort is the

sad, yet tender light which plays around the memory of those who died to make it otherwise! The poor honors we show to them

are as much shown to ourselves, and still more to humanity.--Respect to the memory of the worthy dead is older than civilization.

In all ages, and among all nations and peoples, from those "who dwell within the gates of the rising sun," to those who behold

his mightier light give place to the dreamy dominions of the evening star, it has been usual to revere those who died for

their country, and to celebrate their virtues with the highest funeral honors.

Our noble country-women, abounding in that tenderness which ever cleaves

to misfortune, have undertaken this pious duty. But you must help them, the whole people of the South must help; and small,

indeed, will be the hopes we may claim of the living if, by refusing you show yourselves insensible to the virtues of the

dead. I hope yet to see the honored dust of every Southern soldier reverently gathered up, and placed where gentle hands can

show, by beautifying and adorning his quiet home, that we love him all the same, and bless him all

Page 16

the more, though he died in vain. And in due time, I doubt not, monuments of marble and granite will tell the stranger

how North Carolina cherishes the memory of her illustrious children.

"Tread lightly,--'tis a soldier's grave,

This lonely, mossy mound,--

And yet, to hearts like mine and thine,

It should be holy ground.

Tread lightly,--for this man bequeathed,

Ere laid below this sod,

His ashes to his native land,

His gallant soul to God!"

The time is not far distant, when as citizens, I trust, you will be permitted

to take a part in the government of your country. The path of the statesman for the past decade has been beset with peculiar

difficulties; nor is it likely that the surroundings of the present period will prove less embarrassing to any public man

honestly seeking his country's good. The lessons of experience would make us all wise, if they were not forgotten. In taking

whatever positions your talents or inclinations may cause to be assigned you, my most solemn injunction would be to burn into

your memories, forever, the teachings of the terrible experience of the past five years. The great problem we have just worked

out is full of mighty meaning, its theorem is demonstrated in characters of "fraternal blood," and all its corollaries teem

with changes of power and the downfall of systems. Let it ever be before your eyes, and learn of it, among other wise things,

that the yielding to blind passions and personal resentments, when the happiness of thousands is entrusted to your judgment,

is a crime for which God will hold you accountable. The subjection of every passion and prejudice in the breast, to

the cooler sway of judgment and reason, when the common welfare is concerned, is the first victory to be won in a political

career. Without it, you can win no other in which your country can rejoice. The philosophy of politics exhibits many instructive

phenomena, which you should carefully study. The federative system of separate and quasi-independent States, which composed

the American Union, embraced many peculiar features in relation to the science of government, little known or practiced by

other nations. Years ago, M. Guizot pronounced it the most difficult and complex in the world; an opinion which the infinite

disagreements of our own statesmen, in regard to its power and limitations, have amply

Page 17

justified. Its structure, originally, was not unlike the planetary system; as each State was assigned, by its authors,

an orbit in which to move around the General Government as a grand centre. The dangers, against which its founders seemed

most anxious to provide, were to arise from the imperfect balancing of the centrifugal and centripetal forces, a predominance

of either being esteemed fatal. Should the former prevail, the Government would be destroyed by the flying off of the States,

or the dismemberment of its parts. This would be secession.--Should the latter predominate, there would be an end of the system,

by the crushing out and merging of all the parts in the Central Government. This would be consolidation. It was believed that

the Constitution (the law of gravitation) had so wisely distributed its forces that each would act, in accordance with the

original design, without destroying the other. But these fond hopes were doomed to a terrible disappointment. Whether it be

that, as history teaches, there has been a constant tendency to centralization among all governments which had maintained

and thrown off the feudal system; or that no written constitution can stand the strain of civil war; or simply that men, in

times of great excitement, cannot preserve judgment to discern the right from the wrong, or integrity enough to keep intact

an official oath, it is needless on the present occasion to inquire. The recent attempt, on the part of a minority of the

States, to withdraw from the system, was successfully resisted by the majority, in the name and by the authority of the Central

Government. In order to effect this, powers were claimed and exercised by the latter, as the contest proceeded, higher and

more extraordinary than the wildest consolidationist ever dreamed of asserting before. This destroyed, in letter and spirit,

the original compact, utterly and absolutely; and so disturbed the whole system that, in the very nature of things, it is

impossible for it to oscillate into place again. The predominance of the centripetal power is complete, and the results established,

logically, are that the States cannot withdraw, that they are subject to coercion, not only as to their external relations,

but as to their internal policy, their domestic laws, and everything else whatsoever pertaining to sovereignty. It does

not logically follow, however, not even by the logic of revolutions,

Page 18

that, having neither the legal nor the physical power to withdraw, they are yet out of the Union. That were, indeed, a

moral and a physical impossibility. The very flower of the prerogative of the States is, therefore, swept away by the decision

of this tribunal which is the last resort of kings, and to which a conquered people can interpose no demurrer.

Such is now the actual state of things, unfortunate as we may regard it,

and contrary as it may seem to all of our ideas of the true purposes of the government. But it is our country still,

and if it cannot be governed as we wish it, it must yet be governed some other way; and it is still our duty to labor

for its prosperity and glory, with ardor and sincerity. I earnestly urge upon you the strictest conformity of your conduct

to the situation; to what the government actually is, not what you may think it ought to be. It is our bounden duty as honest

men to give our new formed institutions a full and fair trial--especially the new system of labor--and if they prove better

than the old, let us forget our sufferings and be thankful. And let us not doubt, if the occasion should ever come, that,

for the sake of her own theory, Massachusetts will cheerfully submit to the same degradation which North Carolina has borne.

In the discussion and progress of political questions, you will mostly

find that there are practically three divisions of the people, though there generally appear but two. Two of these occupy

the extremest opposite positions, whilst the third, usually denominated conservative, stands between. This class generally

exceeds either or both of the others in numbers, and in the character and worth of its leaders. Could it always rule, whilst

there would certainly be less of progress, there would yet be less of civil commotion, and far more of true happiness. But

strange to say, though in a majority, this class is seldom in power; for paradoxical as it may appear, the extremists are

nearer to each other than to the intermediate class, and generally combine to overcome it. It is, moreover, a well known defect

of popular governments, that they are prone to mistake the zeal and earnestness of the extremists for sound policy, which

contributes further to their triumph. The cooler wisdom of the conservative statesman is generally appreciated after the mischief

is done. Those bold and striking qualities, so apt to captivate the young and enthusiastic, in war and in politics, are mostly

Page 19

dangerous to good government. And yet mankind have been ever eager to be deceived by them. Even history, stern and dignified,

lends itself, perhaps unconsciously, to the damaging delusion. Whilst page after page paints the glories of the hero who plunged

his country into war, and brought desolat on to the doors of his people, a few brief and passing lines

suffice for the sagacious statesman who has honored his humanity by preventing slaughter. It is to some extent so, in the

nature of things. The great deeds done are tangible and real; the great calamities avoided are only in the mind, and

we cannot fully grasp them. Just as the sublime description of Dante's Inferno, with all the powers of the most vivid imagination,

fails to inspire an idea of torture half equal to that which we feel by holding the finger for one moment in the blaze of

a candle.--But if history could be differently written, and were it possible to set against what this great man has done,

charged with the misery which he inflicted, that which another greater and better man has not done, credited with the

suffering which he has spared his people, how different would be the verdict of posterity! and how naked would many

a popular hero appear! Alas, alas! why will civilization permit its true heroes to sleep in forgotten graves, while marble

and bronze celebrate the virtues of those whose greatness consisted in their power to inflict wretchedness?

There is no more valuable lesson to be learned from the troubled and conflicting

scenes of the recent past, than the obvious value of self-respecting consistency to the character of a public man. And this,

not in the narrow and popular sense of that much abused term, as meaning an unchanging adherence to one opinion or set of

opinions. The dullest intellect and the meanest spirit can not only do that, but is most apt to do it; whilst wise men see

the necessity of changing as often as the ever-varying phases of the case may render it indispensable; as a good general changes

front so often as it is required in order to face the enemy. But all public men should propose certain great truths or principles

as their objects to be attained--never to be abandoned except upon the clearest convictions of their falsity--and though the

means, by which those principles should be preserved, may be varied to suit expediency, through good and evil report the great

objects should be conscientiously adhered to.--

Page 20

This is consistency. You will find it not only the best policy for the truth's sake, but to inspire confidence. For without

truth there can be no confidence, and without confidence governments cannot, any more than armies, be led to victory. A blunder,

honestly confessed, is already half atoned; presisted in wilfully, it perpetuates ruin and becomes

a crime. Nor is it excusable to attempt the extenuation of one blunder, by confessing to another; or to refuse to your confederates

in error the same mercy which has been extended to you. It is a mean plea, and one of a meaner culprit, which tries to evade

the halter for the first crime, by owning that he infinitely more deserved a hanging for the second: and a politician, who

cannot forgive as he is forgiven, is both a bad statesman and a bad man. Faith, honestly kept, even in the worst of causes,

can never fail to inspire respect in the breast of a generous foe, which not even the bitterness of a civil war can destroy.

In this connection, I would recommend to your earnest consideration, the masterly delineation of the character of Shaftesbury

by Macaulay, as instructively portraying a set of men who swarm in times of revolution, and are justly regarded as greatly

aggravating the public misfortunes.

With regard to current political events and speculations of the future,

of which we are permitted to be only quiet, though deeply interested spectators, I do not, altogether, share the general alarm

that pervades the Southern mind. The taunts, the gibes, the sneers and the vulgar triumphs of ignoble spirits, which so annoy

and mortify, were to be expected. Their brief day will soon pass. They were born of the license of victory, and will endure

no longer than the excitements of the occasion serve to render good men ungenerous. Happily it is not in the nature of man

always to hate; and the reign of the bad passions is short-lived. It is hardly possible that hatred will long continue between

two communities brought into daily, familiar intercourse, when the subjects of contention have been removed, and when mutual

interests and common associations invite to good will. "The disposition of man is so kindly and good," says M. Guizot, in

his History of Civilization, "that it is almost impossible for a number of individuals to be placed for any length of time

in a social situation, without giving birth to a certain moral tie between them;

Page 21

sentiments of protection, of benevolence, of affection spring up naturally." As the passions cool, reason must return,

and with reason comes justice, whose inseparable companion is fraternity. If it were not so, there would be no end of strife.

Could we calmly and impartially consider now the depth and fierceness of the passions which so lately raged in the hearts

of all, it would doubtless appear that the embers of bitterness, though still burning, were yet flickering day by day to their

extinction, with a rapidity for which we should fervently thank God. The reaction to this great stretch of human passion is

sure to come; it will come soon, and, like everything; else American, it will come with power. Magnanimity, the greatest

of national as of private virtues, will once more reign, and will soon shame the Northern manhood from assailing a brave people

who no longer resist. They have already a shining example in their Chief Magistrate of the Republic, worthy of all honor and

emulation. In contemplating his official action toward those who were so lately his extremest enemies, and observing how he

has magnanimously sunk what must have been the feelings of the man in those of the patriot and the statesman, and how

his keen intellect has appreciated the true situation of affairs, disappointing none so much as those who undervalued him,

we are at once reminded of that splendid burst of eloquence uttered by Cicero on the occasion of returning the thanks of the

Senate to Cęsar for the pardon and restoration of his enemy, Marcellus. Though fulsome and extravagant--a fault both of the

orator and his age--it yet contains so fine a tribute to a great virtue that I cannot refrain from quoting a portion of it.

Addressing Cęsar, he said: "You have conquered nations brutally barbarous, immensely numerous, boundlessly extended, and furnished

with everything that can make war successful. Yet all these, their own nature and the nature of things made it possible to

conquer. For no strength is so great as to be absolutely invincible, and no power so formidable as to be proof against superior

force and courage. But the man who subdues passion, stifles resentments, tempers victory, and not only rears the noble, wise

and virtuous foe when prostrate, but heightens his former dignity, is a man not to be ranked with the greatest mortals, but

resembles a god!" Well might our Christian religion teach us the sublime duty of mercy to the fallen foe,

Page 22

when even the splendid imagery of the greatest of ancient orators, in the midst of the highest types of heathen civilization,

could find no nobler attribute with which to invest his deities!

What a genuine stroke of statesmanship this noble clemency of President

Johnson was; and how warmly appreciated it has been, not only by its poor and afflicted recipients, but by the whole world!

How soon was the terrible suspense and troubled anxiety, which filled all the land after the surrender of our armies, turned

into blessing and praise! Through him, and such as he, we begin to see how it is possible to love our whole country once more.

Through him it is--far more than test oaths and similar feeble contrivances--that the deep and sincere feeling pervades all

the South to submit nobly to, and abide honestly by, all the results of the war. The true bonds to impose upon a conquered

people are wrought in the magnanimity of the conquerors. The mightiest cables of iron ever forged in the mammoth furnaces

of the land, though long enough and strong enough to link together, indissolubly, the countless fleets of the Republic, in

the midst of the wildest tempest that ever strewed our shores with the wreck of stranded ships, are yet not so strong as the

cords of lasting gratitude with which a generous people receive the magnanimous kindness of those late foes, with whom they

have just measured strength in many a manly field; especially when those kindnesses reveal glimpses of an ancient and once

glorious brotherhood! May God in his infinite mercy grant that these glimpses may ripen into full and everlasting realities,

and that the spirit of reconciled brothers may again animate all the people of this mighty land, which has hitherto rendered

it so renowned among the nations!

Respect must be the foundation of all national as well as all private friendships.

And when the bitter pangs of the recent struggle are buried, as they must be, there will remain no reason why mutual respect

should not prevail; unless, indeed, our conduct, in the hour of our humiliation, should furnish it. Here we have been in danger

of the most cruel mistake. For grievously do we deceive ourselves, if we suppose that we inspire respect in the bosoms of

our late enemies, in proportion as we voluntarily practice uncalled for self-abasement. We can but inspire disgust alone when

we thus show

Page 23

them that their vast armies and great generals were, after all, only employed to subdue a race of mean-spirited dirt-eaters,

from among whom the truly noble had been mercifully slain in the battle! The severest contempt of civilization is richly merited

by a people who would cast obloquy upon the ashes of their own dead children; and as the best evidence of the truth and sincerity

of their present obligations aver the utter falsity of their former ones! That a man must be necessarily telling truth to-day,

because he was undoubtedly a liar only so late as yesterday! When we approach our conquerors with such evidences of loyalty,

there is little wonder that we inspire contempt and suspicion. Surely the fact of our submission can be sufficiently

complete and sincere, without making the manner thereof such as to forfeit the respect either of ourselves or our late foes.

Our great country, of the South, with its fertile soil, happy climate,

and boundless resources, excites the highest admiration of the Northern people. The vigorous scope and conservative tendency

of our statesmanship they have never failed to respect, and have even acknowledged that it has controlled, to a great degree,

the policy of the Government, in and from its organisation; thereby giving us credit for much of its

power and glory. They cannot but remember that it was Southern farmer-statesmen of Mecklenburg, North Carolina, who sounded

the key note of Independence in 1775, in that celebrated paper, in which, as pronounced by their own

Adams, "the genuine sense of America at that moment was never so well expressed before nor since;" and by the side of which

Tom. Paine's famous "Common Sense" tracts, according to the same author, were a "poor, ignorant, malicious, crapulous mass."

They cannot forget that the other world-renowned declaration, that of 1776, was from the brain of a Southern statesman; and

that it was the genius of a Southern general, who, in making good its bold assumptions, rendered himself the most illustrious

of mankind. Nor yet can they forget that in two foreign wars the most signal glory shed upon our country's arms was by the

skill and valor of Southern commanders, followed by Southern volunteers. And certainly they cannot overlook, even now, that

fund of military genius, intrepid gallantry, heroic constancy under misfortune, and all the traits which mark a noble people,

that we have so

Page 24

lately exhibited. I would as soon believe that there was no room for such things in the breasts of men as truth and honor,

as that every soldier in the Army of the Potomac, from its General to the humblest private that followed its banners, did

not, in his heart, respect and honor the lofty courage, consummate skill, and patient constancy of that other army,

which, though vastly inferior in numbers and appointments, yet kept it four years on the short but bloody journey from the

Potomac to the James, and piled every inch of its pathway with ghastly monuments of the slain! Let not the sneer of

the supercilious, nor the taunt of the ungenerous, over our final defeat, deceive us in this matter, or cause us to abate

one jot of our just claims to the high place in history which posterity will award us. That, which has so moved upon the sympathy

and admiration of the world, has already excited, and will yet more excite, that of our Northern friends. And in due time

if we faint not, we shall reap those fruits which the generous and the better feelings of men never fail to bear. Years hence

when, as I trust, time and a juster policy shall have healed many an ugly wound, and quieted many an aching heart, the story

of the great civil war will be read around a thousand firesides among the homes of the North, and as the glowing recital burns

upon the ear, how that one-fourth of the people of the United States, without manufactures and almost without arms, without

ships, arsenals or foundries, shut out from all the world by a sealed blockade, for four long and terrible years fought back

and kept at bay the other three-fourths, who were aided by manumitted slaves, who had great navies, their own and the workshops

of the world at their control, and whose slaughtered armies were filled up again and again, from the swarming populations

of Europe; and how the ragged battalions of the South, under Lee and Jackson, and Johnson, and Hoke, and Pender, and Early,

struggled with the great armies of McClellan and Grant, and Sherman, and Sheridan, and Buell, until the world was full of

their fame; a thousand fathers, burning with the unconfessed pride of country and of race, will say to their sons who wonder

how all this could have been: "These were the countrymen of Washington and Jackson. These were Americans--none but American

citizens could have done these things!"

And now what is said is said. Would that it were better

Page 25

said. The one great theme--our country and its sufferings--so fills my heart, as I presume it does all hearts, that I have

spoken much of it. Your letter of invitation likewise implied that, though it was a literary occasion, a purely literary address

was not expected. I trust that I may have assisted somewhat in pointing you to those paths of usefulness and honor, in treading

which you may best serve your dear old Mother, rent and ruined as she is. Her eyes are turned now yearningly and with maternal

pride, toward her educated sons, pleading that they will hold up her arms that her evil days may be few. May this honored

and reviving University speedily, and from time to time, open again its gates and send forth to the work of the regeneration

of their country as many high-souled and generous, brave and enthusiastic youths, as rushed through its portals to untimely

graves during the years of our tribulation. I could not endure to live but for the comforting hope that compensating years

of peace and happiness are yet in store for those who have struggled so manfully and endured so nobly. Having gone down into

the very lowest depths of the fiery furnace of affliction, seven times heated by the cruel malice of civil war, I believe

there will yet appear, walking with and comforting our mourning people, One, whose form is like unto that of the Son of God!

© This work is the property of the University of North Carolina at

Chapel Hill. It may be used freely by individuals for research, teaching and personal use as long as this statement of availability

is included in the text.

Recommended Reading: Zeb Vance: North Carolina's Civil War Governor

and Gilded Age Political Leader (Hardcover) (528 pages) (The University of North Carolina Press). Description:

In this comprehensive biography of the man who led North Carolina through the Civil War and,

as a U.S. senator from 1878 to 1894, served

as the state's leading spokesman, Gordon McKinney presents Zebulon Baird Vance (1830-94) as a far more complex figure than

has been previously recognized. Vance campaigned to keep North Carolina in the Union, but

after Southern troops fired on Fort Sumter,

he joined the army and rose to the rank of colonel. Continued below.

He was viewed as a champion of individual

rights and enjoyed great popularity among voters. But McKinney

demonstrates that Vance was not as progressive as earlier biographers suggest. Vance was a tireless advocate for white North Carolinians in the Reconstruction Period, and his policies and positions often favored the rich

and powerful. McKinney provides significant new information about Vance's third governorship,

his senatorial career, and his role in the origins of the modern Democratic Party in North

Carolina. This new biography offers the fullest, most complete understanding yet of a legendary North Carolina leader.

Related Reading:

Recommended

Reading: War Governor of the South: North Carolina's Zeb Vance in the Confederacy

(New Perspectives on the History of the South) (Hardcover) (288 pages) (University Press of Florida). Description: Zebulon B. Vance, governor of North

Carolina during the devastating years of the Civil War, has long sparked controversy and spirited

political comment among scholars. He has been portrayed as a loyal Confederate, viciously characterized as one of the principal

causes of the Confederate defeat, and called “the Lincoln

of the South.” Joe A. Mobley clarifies the nature of Vance’s leadership, focusing on the young governor’s

commitment to Southern independence, military and administrative decisions, and personality clashes with President Jefferson

Davis. Continued below.

As a confirmed

Unionist before the outbreak of the war, Vance endorsed secession reluctantly. Elected governor in 1862, Vance managed to

hold together the state, which was divided over support for the war and for a central government in Richmond.

Mobley reveals him as a man conflicted by his prewar Unionist beliefs and the necessity to lead the North Carolina war effort

while contending with widespread fears created by Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and such issues as the role of

women in the war, lawlessness and desertion among the troops, the importance of the state’s blockade-runners, and the

arrival of Sherman’s troops. While the governor’s temperament and sensitivity to any perceived slight to him -

or his state - made negotiations between Raleigh and Richmond

difficult; Mobley shows that in the end, Vance fully supported the attempt to achieve southern independence.

Recommended Reading: North Carolinians in the Era of the Civil War and Reconstruction (The University of North Carolina Press). Description: Although North Carolina was a "home front" state rather than a battlefield state for most of the

Civil War, it was heavily involved in the Confederate war effort and experienced many conflicts as a result. North

Carolinians were divided over the issue of secession, and changes in race and gender relations brought new controversy.

Blacks fought for freedom, women sought greater independence, and their aspirations for change stimulated fierce resistance

from more privileged groups. Republicans and Democrats fought over power during Reconstruction and for decades thereafter

disagreed over the meaning of the war and Reconstruction. Continued below.

With contributions

by well-known historians as well as talented younger scholars, this volume offers new insights into all the key issues of

the Civil War era that played out in pronounced ways in the Tar Heel State.

In nine fascinating essays composed specifically for this volume, contributors address themes such as ambivalent whites, freed

blacks, the political establishment, racial hopes and fears, postwar ideology, and North Carolina women. These issues of the

Civil War and Reconstruction eras were so powerful that they continue to agitate North Carolinians today.

Recommended

Reading: Bluecoats and Tar Heels: Soldiers and Civilians

in Reconstruction North Carolina (New Directions

in Southern History) (Hardcover). Description: In Bluecoats and Tar Heels: Soldiers and Civilians in Reconstruction

North Carolina, Mark L. Bradley examines the complex relationship between U.S. Army soldiers and North Carolina civilians

after the Civil War. Continued below...

Postwar violence and political instability led the federal government to deploy elements of the U.S. Army

in the Tar Heel State,

but their twelve-year occupation was marked by uneven success: it proved more adept at conciliating white ex-Confederates

than at protecting the civil and political rights of black Carolinians. Bluecoats and Tar Heels is the first book to focus

on the army’s role as post-bellum conciliator, providing readers the opportunity to discover a rich but neglected chapter

in Reconstruction history.

Recommended Reading: Confederate

Military History Of North Carolina: North Carolina

In The Civil War, 1861-1865. Description:

The author, Prof. D. H. Hill, Jr., was the son of Lieutenant General Daniel Harvey Hill (North

Carolina produced only two lieutenant generals and it was the second highest rank in the army)

and his mother was General “Stonewall” Jackson’s wife's sister. In Confederate

Military History Of North Carolina, Hill discusses North Carolina’s massive task of preparing and mobilizing

for the conflict; the many regiments and battalions recruited from the Old North State; as well as the state's numerous

contributions during the war. Continued below...

During Hill's Tar Heel State

study, the reader begins with interesting and thought-provoking statistical data regarding the 125,000 "Old North State"

soldiers that fought during the course of the war and the 40,000 that perished. Hill advances with the

Fighting Tar Heels to the first battle at Bethel, through numerous bloody campaigns

and battles--including North Carolina’s contributions at the "High Watermark" at Gettysburg--and concludes with Lee's surrender at Appomattox.

Highly recommended!

|