|

|

Missouri Civil War Battles and Timeline of Events

February 6, 1861 - Seize, Control, Enforce. In 1861, the U.S. arsenal

at St. Louis, Missouri, housed 60,000 stands of arms, a number of cannon and large stores of munitions of war. Both Union

and secessionists looked with longing eyes upon the arsenal. Each realized that whichever side gained possession of the arsenal

would control St. Louis, and the side that controlled St. Louis would eventually control the state. Then opposing sides, during

a series of calculated events, vied for control of said arsenal. The arsenal, however, was located in the southern

part of the city, which was occupied almost exclusively by a German population, which was staunchly pro-Union. On February

6, 1861, Captain Nathaniel Lyon marched unopposed into St. Louis at the head of his company from Kansas and secured the

St. Louis Arsenal by direction of President Lincoln. On March 13, Lyon was placed in nominal command of the arsenal.

With an increasing Union presence daily and as a result of martial law that had been imposed in April, the

St. Louis Massacre erupted on May 10. Subsequently there was no longer neutrality; citizens were either Union or Confederate.

March 4-21, 1861 - Missouri

Declares Neutrality. On March 4 the Missouri State Convention begins its meetings in St. Louis, under the presidency of Sterling

"Pap" Price, to consider the secession of the State of Missouri from the Union. On March 5 a military bill, giving the Governor

sweeping military empowerment is proposed, but it is rejected by the Missouri legislature at Jefferson City. On March

9 the Committee on Federal Relations at the Convention in St. Louis issued its report that in a "military aspect secession

and connection with a Southern Confederacy is annihilation for Missouri." It also resolved that 1) "No adequate cause for

the withdrawal of Missouri from the Union." 2) Belief that all the "seceded States would return to the Union if the Crittenden

proposition were adopted". 3) It would "entreat the Federal Government not employ force against the seceding States . . ."

March 11, 1861 - Take that Arsenal! On March 11, Union Gen.

Frank P. Blair requests that Capt. Nathaniel Lyon take command of the troops at the St. Louis Arsenal. On March 21 the Missouri

State Convention adjourns after voting against Secession, stating "no adequate cause [existed] to impel Missouri to dissolve

her connections with the Federal Union." The final vote was 98-1. Missouri attempts neutrality but the Federal invasion

in May pushed many Unionists into the Confederate camp. As in Kentucky, pro-Union and pro-Confederate governments were

established, the latter run in exile by Governor Claiborne F. Jackson. Missouri became a Confederate state in November

1861. Its thriving prewar economy was devastated and its people terrorized by brutal guerrilla warfare.

April 14-17, 1861 - An Unholy Crusade. This

was the situation when on April 14, 1861: Fort Sumter fell before the Confederate guns, and Lincoln issued his proclamation

on the 15th, calling for 75,000 men to quell the rebellion. Missouri's quota was fixed at four regiments, which Gov. Jackson

was requested to furnish. Instead of complying he sent the following reply to Secretary of War, Simon Cameron, on the 17th:

"Your despatch of the 15th inst., making a call on Missouri for four regiments of men for immediate service, has been received.

There can be, I apprehend, no doubt but these men are intended to form a part of the president's army to make war upon the

people of the seceded states. Your requisition, in my judgment, is illegal, unconstitutional, and revolutionary in its objects,

inhuman and diabolical, and cannot be complied with. Not one man will the State of Missouri furnish to carry on such an unholy

crusade."

| Missouri Civil War Timeline Map |

|

| Secession of States and Readmission to Union Dates |

April 19-30, 1861 - President Lincoln Responds. Gov. Jackson's refusal

to furnish the troops called for by the Federal administration gave Gen. Blair his opportunity. On the 19th, he sent

a telegram to Secretary Cameron, advising him to authorize Capt. Lyon by telegraph to muster Missouri's quota into Federal

service. The suggestion was promptly acted upon by the U.S. War Department, and thus the arms and munitions in the arsenal

passed into Lyon's control and were used to equip the Home Guards, which were mustered into the service of the United States. Lyon

assumed temporary command of the Department of the West. A week later (April 30), he received this order from Secretary Cameron:

"The president of the United States directs that you enroll in the military service of the United States loyal citizens of

St. Louis and vicinity, not exceeding, with those heretofore enlisted, 10,000 in number,

for the purpose of maintaining the authority of the United States and for the

protection of the peaceable inhabitants of Missouri; and you will, if deemed necessary, proclaim martial law in the city

of St. Louis." By said direction of the president, Union officials proclaim martial law in the city of St. Louis

on April 30.

May

10, 1861 - Capture the Missouri State Government! On May 10, the state capital was in "receipt of a telegram announcing

that 2,000 Union troops were on their way to Jefferson City to capture the governor, state officers and members of the legislature."

Lincoln had responded to Gov. Jackson by dispatching Union forces to Missouri and imposing martial law on its citizens. The

state government, from legislatures to the governor, was also to be arrested, and a pro-Union provisional government of the

State of Missouri was to be created. Outnumbered and outgunned, members

of the state government fled. Some limited resistance, however, from the citizens of the state was soon silenced by Union

guns. From Union occupation to martial law, many Missourians saw the acts as declaring war on a sovereign state that

had not seceded. This, according to many Missourians, was unconstitutional and tyrannical. One citizen proclaimed: "They [Union]

may seize everything, only to be left with nothing." The citizen was referring to bloody guerrilla warfare to come, which

included burning property, pillaging and killing. Guerrilla warfare, furthermore, was nothing new, because Missouri and Kansas

had experienced it since 1854 with the Border War, aka Bleeding Kansas. Military force, martial law, and an unconstitutional,

unelected pro-Union government was the "rallying call for many who had considered themselves neutral."

May 10-12, 1861 - The St. Louis Massacre began on May 10, 1861, when Union

forces clashed with civilians on the streets of St. Louis, Missouri, resulting in the deaths of at least 28 and injuries

of roughly 100. The events began when Union Captain Nathaniel Lyon, a Radical Republican known for his brazenness, used a

newly mustered force of roughly 3,000 men, many of them German immigrants and members of the Wide Awakes organization,

to arrest a Missouri State Militia encampment located outside of the city. It was widely rumored that the militia intended to

take possession of the hotly contested St. Louis Arsenal, which both Union and Confederate forces desired. After surrounding

the militia encampment Lyon decided to march his prisoners through downtown St. Louis before providing them with a parole

and ordering them to disperse. This march was widely viewed as humiliation for the state forces and immediately angered

citizens who had gathered to watch the commotion. Tensions mounted quickly on the streets as civilians hurled fruit, rocks,

and insults at Lyon's troops and some of the soldiers returned the favor. Nobody knows exactly what happened to provoke

the massacre, but the standard report says that a drunkard stumbled into the path of the marching soldiers and got into

an altercation with some of them. Weapons were drawn by both the soldiers and civilians and shots rang out. Some of the

soldiers formed a line and fired into the nearby crowd. Violence continued for the next two days resulting in the death of

at least 7 more civilians, who were shot by federal troops patrolling the streets. The St. Louis Massacre, as it came

to be called, quickly sparked an outcry across the state of Missouri. Prior to that point most Missourians had been moderate

Unionists who were opposed to secession and war. Popular opinion transformed overnight, causing many former Unionists

including former Governor Sterling Price to advocate secession and producing a state that was bitterly divided between

Union and Confederate sympathizers.

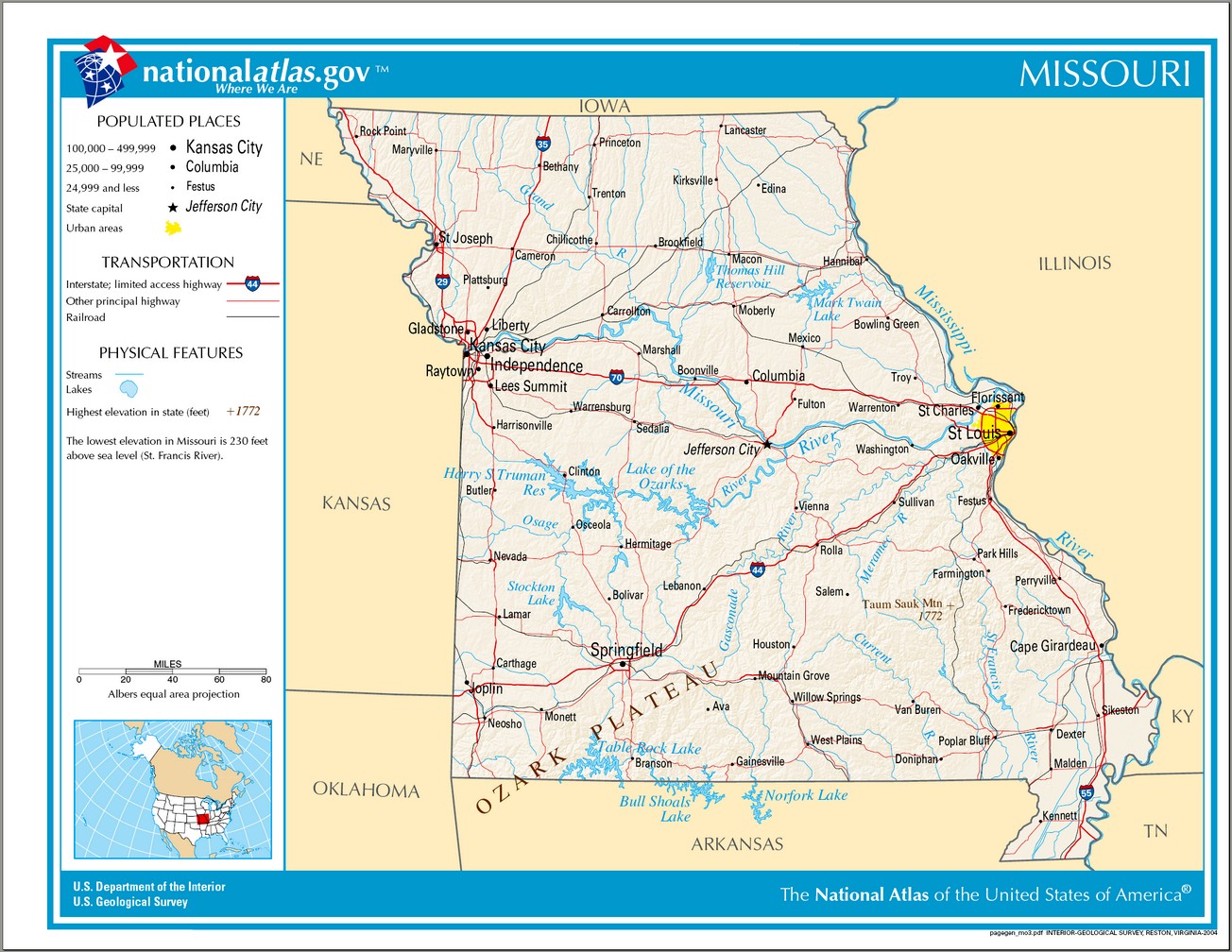

| Missouri Civil War Battle Map |

|

| Map of Missouri Civil War Battles and Battlefields |

June 17, 1861 - Battle of Boonville (aka First Battle of Boonville). Claiborne

Jackson, the pro-Southern Governor of Missouri, wanted the state to secede and join the Confederacy. Union Brig. Gen. Nathaniel

Lyon set out to suppress Jackson's Missouri State Guard, commanded by Sterling Price. Reaching Jefferson City, the state capital,

Lyon discovered that Jackson and Price had retreated towards Boonville. Lyon reembarked on steamboats, transported his men

to below Boonville, marched to the town, and engaged the enemy. In a short fight, Lyon dispersed the Confederates, commanded

on the field by Col. John S. Marmaduke, and occupied Boonville. This early victory established Union control of the Missouri

River and helped douse attempts to place Missouri in the Confederacy. Estimated Casualties: 81 total (US 31; CS 50).

July 5, 1861 - Battle of Carthage. Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon had chased

Missouri Governor Jackson and approximately 4,000 State Militia from the State Capital at Jefferson City and from Boonville,

and pursued them. Col. Franz Sigel led another force of about 1,000 into southwest Missouri in search of the governor

and his loyal troops. Upon learning that Sigel had encamped at Carthage, on the night of July 4, Jackson took command

of the troops with him and formulated a plan to attack the much smaller Union force. The next morning, Jackson closed

up to Sigel, established a battle line on a ridge ten miles north of Carthage, and induced Sigel to attack him. Opening

with artillery fire, Sigel closed to the attack. Seeing a large Confederate force—actually unarmed recruits—moving

into the woods on his left, he feared that they would turn his flank. He withdrew. The Confederates pursued, but Sigel conducted

a successful rearguard action. By evening, Sigel was inside Carthage and under cover of darkness; he retreated to Sarcoxie.

The battle had little meaning, but the pro-Southern elements in Missouri, anxious for any good news, championed their first

victory. Estimated Casualties: 244 total (US 44; CS 200).

August 10, 1861 - Battle of Wilson's Creek (aka Battle of Oak Hills).

The Battle of Wilson's Creek, fought on August 10, 1861, was the first major Civil War engagement west of the Mississippi

River, involving about 5,400 Union troops and 12,000 Confederates. Union Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon's Army of the West

was camped at Springfield, Missouri, with Confederate troops under the commands of Brig. Gen. Ben McCulloch and Sterling "Pap"

Price, commander of the Missouri secessionist militia, approaching. On August 9, both sides formulated plans to attack

the other. About 5:00 a.m. on the 10th, Lyon, in two columns commanded by himself and Col. Franz Sigel, attacked the

Confederates on Wilson's Creek about 12 miles southwest of Springfield. Rebel cavalry received the first blow and fell back

away from Bloody Hill. Confederate forces soon rushed up and stabilized their positions. The Confederates attacked the Union

forces three times that day but failed to break through the Union line. Lyon was killed during the battle (the first

Union general to be killed in combat) and Maj. Samuel D. Sturgis replaced him. Meanwhile, the Confederates had routed Sigel's

column, south of Skegg's Branch. Following the third Confederate attack, which ended at 11:00 am, the Confederates withdrew.

Sturgis realized, however, that his men were exhausted and his ammunition was low, so he ordered a retreat to Springfield.

The Confederates were too disorganized and ill-equipped to pursue. This Confederate victory buoyed southern sympathizers in

Missouri and served as a springboard for a bold thrust north that carried Price and his Missouri State Guard as far as

Lexington. Wilson's Creek, the most significant 1861 battle in Missouri, gave the Confederates control of southwestern Missouri. The

battle led to greater federal military activity in Missouri, and set the stage for the Battle of Pea Ridge in March 1862.

Estimated Casualties: 2,330 total (US 1,235; CS 1,095).

August-September, 1861 - Frémont's Emancipation Proclamation. On August

30, Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont, commander of the Union Army in St. Louis, proclaimed that all slaves owned by Confederates

in Missouri were "forever free." He had not informed President Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln was furious when he heard the

news as he feared that this action would force slave-owners in Border States to help the Confederates. Lincoln asked Frémont to modify his proclamation to conform to official

policy, which under the Confiscation Act of 1861, freed only those slaves used by Confederates to aid the war effort and did

not extend to general abolition. Frémont refused. This placed the president, who later called Frémont's act "dictatorial",

in a very difficult political position. He could not risk alienating the conservatives in this crucial Border State;

yet he did not wish to upset the Radical Republicans who were pressing for abolition. The president felt he needed to be cautious;

at this stage of the war, Union victories were not numerous enough to justify bold political actions.

Lincoln wrote to Frémont: "Can it be pretended that it is any longer

the government of the U.S.—any government of Constitution and laws—wherein a General, or a President, may make

permanent rules of property by proclamation." The President revoked Frémont's proclamation on September 11. On October 24,

Frémont was relieved of his command and replaced by Gen. Henry W. Halleck, who assumed command of the Department of the Missouri

on November 19, 1861, and issued an order forbidding runaway slaves from seeking permission to be protected by the Union Army.

Radical Republicans were furious with Lincoln for sacking Frémont. The Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, William P.

Fessenden, described Lincoln's actions as "a weak and unjustifiable concession in the Union men of the Border States." Charles

Sumner wrote to Lincoln complaining about his actions and remarked how sad it was "to have the power of a god and not use

it godlike".

September 2, 1861 - Battle of Dry Wood Creek (aka Battle of Big Dry Wood Creek or

Battle of the Mules). Col. J.H. Lane’s cavalry, comprising about 600 men, set out from Fort Scott to learn the whereabouts

of a rumored Confederate force. They encountered a Confederate force, about 6,000-strong, near Big Dry Wood Creek. The Union

cavalry surprised the Confederates, but their numerical superiority soon determined the encounter’s outcome. They forced

the Union cavalry to retire and captured their mules, and the Confederates continued on towards Lexington. The Confederates

were forcing the Federals to abandon southwestern Missouri and to concentrate on holding

the Missouri Valley. Estimated Casualties: Total unknown (US 14; CS unknown).

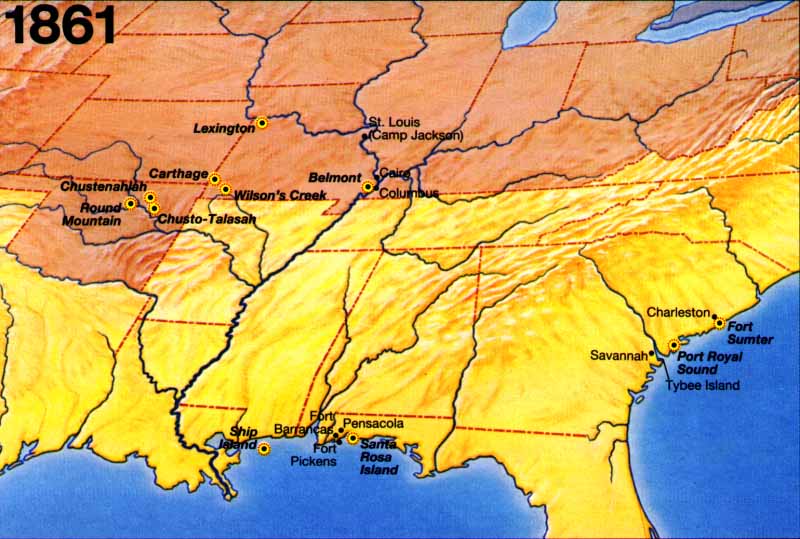

| Map of Civil War Western Theater in 1861 |

|

| Map of Civil War and Western Theater in 1861 |

September 13-20, 1861 - Battle of Lexington (aka First Battle of Lexington

or Battle of the Hemp Bales). Following the victory at Wilson’s Creek, the Confederate Missouri State Guard, having

consolidated forces in the northern and central part of the state, marched, under the command of Maj. Gen. Sterling Price,

on Lexington. Col. James A. Mulligan commanded the entrenched Union garrison of about 3,500 men. Price’s men first encountered

Union skirmishers on September 13 south of town and pushed them back into the fortifications. Price, having bottled the Union

troops up in Lexington, decided to await for his ammunition wagons, other supplies, and reinforcements before assaulting

the fortifications. By the 18th, Price was ready and ordered an assault. The Missouri State Guard moved forward amidst heavy

Union artillery fire and pushed the enemy back into their inner works. On the 19th, the Rebels consolidated their positions,

kept the Yankees under heavy artillery fire and prepared for the final attack. Early on the morning of the 20th, Price’s

men advanced behind mobile breastworks, made of hemp, close enough to take the Union works at the Anderson House in a final

rush. Mulligan requested surrender terms after noon, and by 2:00 pm his men had vacated their works and stacked their arms.

This Unionist stronghold had fallen, further bolstering southern sentiment and consolidating Confederate control in the Missouri

Valley west of Arrow Rock. Estimated Casualties: 1,874 total (US 1,774; CS 100).

September 17, 1861 - Battle

of Liberty (aka Battle of Blue Mills Landing or Battle of Blue Mills). General D.R. Atchison left Lexington on September

15, 1861, and proceeded to Liberty where he met the Missouri State Guard. On the night of September 16-17, his force crossed

the Missouri River to the south side and prepared for a fight with Union troops reported to be in the area. At the same time,

Union Lt. Col. John Scott led a force of about 600 men from Cameron, on the 15th, towards Liberty. He left his camp in Centreville, at 2:00 am on the 17th. He arrived in Liberty, sent scouts out to find the enemy,

and, about 11:00 am, skirmishing began. At noon, Scott marched in the direction of the firing, approached Blue Mills Landing

and, at 3:00 am, struck the Confederate pickets. The Union force began to fall back, though, and the Rebels pursued for some

distance. The fight lasted for an hour. The Confederates were consolidating influence in northwestern Missouri. Estimated

Casualties: 126 total (US 56; CS 70).

October 21, 1861 - Battle of Fredericktown. Two Union columns, one

under Col. J.B. Plummer and another under Col. William P. Carlin, advanced on Fredericktown to overtake Brig. Gen. M. Jeff

Thompson and his men. On the morning of October 21, Thompson’s force left Fredericktown headed south. About twelve miles

out, Thompson left his supply train in a secure position and returned toward Fredericktown. He then learned that Union forces

had occupied Fredericktown, so Thompson spent the morning attempting to discern the enemy numbers and disposition. Unable

to do so, he attacked anyway, around noon. Plummer, with his force and a detachment of Col. William P. Carlin’s troops,

met the Rebel forces outside town and a two-hour fight ensued. Overwhelming Union forces took their toll, and Thompson’s

men retreated. Union cavalry pursued. Fredericktown cemented Union control of southeastern Missouri. Estimated Casualties:

Total unknown (US unknown; CS 62).

October 25, 1861 - Battle of Springfield (aka First Battle of Springfield

or Battle of Zagonyi’s Charge). Having accomplished little since taking command of the Western Department, with

headquarters in St. Louis, Missouri, Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont formulated a plan to clear Maj. Gen. Sterling Price’s

Rebels from the state and then, if possible, carry the war into Arkansas and Louisiana. Leaving St. Louis on October 7, 1861,

Frémont’s combined force eventually numbered more than 20,000. His accompanying cavalry force, numbering 5,000 men and

other mounted troops, included Maj. Frank J. White’s Prairie Scouts and Frémont's Body Guards under Maj. Charles Zagonyi.

Maj. White became ill and turned his command over to Zagonyi. These two units operated in front of Frémont’s army to

gather intelligence. As Frémont neared Springfield, the local state guard commander, Col. Julian Frazier, sent out requests

to nearby localities for additional troops. Frémont camped on the Pomme de Terre River, about 50 miles from Springfield. Zagonyi’s

column, though, continued on to Springfield, and Frazier’s force of 1,000 to 1,500 prepared to meet it. Frazier set

up an ambush along the road that Zagonyi travelled, but the Union force charged the Rebels, sending them fleeing. Zagonyi’s

men continued into town, hailed Federal sympathizers and released Union prisoners. Leery of a Confederate counterattack, Zagonyi departed Springfield before night, but Frémont’s army returned, in force, a

few days later and set up camp in the town. In mid-November, after Frémont was sacked and replaced by Maj. Gen. Hunter, the

Federals evacuated Springfield and withdrew to Sedalia and Rolla. Federal troops reoccupied Springfield in early 1862 and

it was a Union stronghold from then on. This engagement at Springfield was the only Union victory in southwestern Missouri

in 1861. Estimated Casualties: 218 total (US 85; CS 133).

October 28, 1861 - Missouri Joins the Confederacy. Deposed Missouri Governor

Claiborne F. Jackson Jackson convenes a rump convention in Neosho, MO., which passes an ordinance of secession. Missouri joins

the Confederate States of America in November 1861.

November

7, 1861 - Battle of Belmont. On November 6, 1861, Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant leaves Cairo, Illinois, by steamers, in conjunction

with two gunboats, to make a demonstration against Columbus, Kentucky. The next morning, Grant learns that Confederate

troops had crossed the Mississippi River from Columbus to Belmont, Missouri, to intercept two detachments sent in pursuit

of Brig. Gen. M. Jeff Thompson and, possibly, to reinforce Maj. Gen. Sterling Price's force. Grant lands on the Missouri

shore, out of the range of Confederate artillery at Columbus, and starts marching to Belmont. At 9:00 a.m. an engagement begins.

The Federals rout the Confederates out of their Belmont cantonment, destroying the Rebel supplies and equipment since they

did not have the means to carry them off. The scattered Confederate forces reorganize and receive reinforcements from

Columbus. Counterattacked by the Confederates, the Union force withdraws, reembarks, and returns to Cairo. Grant did

not accomplish much in this operation, but, at a time when little Union action occurred anywhere, many were heartened by any

activity. Estimated Casualties: 1,464 total (US 498; CS 966).

December 28, 1861 - Battle of Mount Zion Church. Brig. Gen. Benjamin

M. Prentiss led a Union force of 5 mounted companies and 2 companies of Birge’s sharpshooters into Boone County to protect

the North Missouri Railroad and overawe secessionist sentiment there. After arriving in Sturgeon on December 26, Prentiss

learned of a band of Rebels near Hallsville. He sent a company to Hallsville the next day that fought a Confederate force

under the command of Col. Caleb Dorsey and suffered numerous casualties, including many taken prisoner, before retreating

to Sturgeon. On the 28th, Prentiss set out with his entire force to meet Dorsey’s Rebels. He routed one company of Confederates

on the road from Hallsville to Mount Zion and learned that the rest of the force was at Mount Zion Church. Prentiss headed

for the church. After a short battle, the Confederates retreated, leaving their killed and wounded on the battlefield and

abandoning many animals, weapons, and supplies. This action and others curtailed Rebel recruiting activities in Central Missouri.

Estimated Casualties: 282 total (US 72; CS 210).

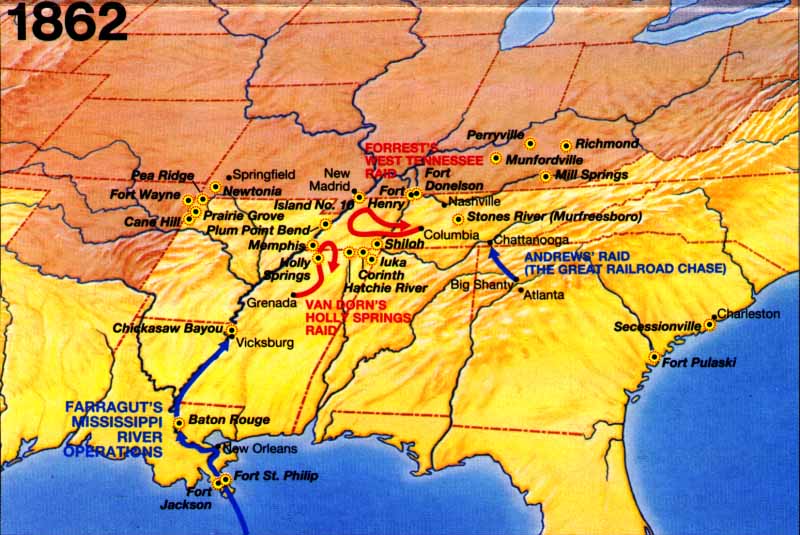

| Map of Civil War Western Theater in 1862 |

|

| Map of Civil War and Western Theater in 1862 |

January 8, 1862 - Battle of Roan's Tan Yard (aka Battle of Silver Creek).

Rumors and sightings of a Confederate force in the Howard County area had circulated for more than a week, but the Union troops

could not locate them. On January 7, 1862, information came to hand that Col. J.A. Poindexter and his Confederate force were

camped on Silver Creek. Detachments from various Union units came together and headed towards the Confederate camp which was

about 14 miles northwest of Fayette. After finding the camp, the force attacked, routing the enemy and sending those that

were not killed, wounded, or captured fleeing for safety. Afterwards, the Union force destroyed the camp to prevent its further

use. The Confederates could no longer use their Randolph County base for recruiting and raiding. Estimated Casualties: 91

total (US 11; CS 80).

February 28-April 8, 1862 - Battle of New Madrid and Island Number Ten.

Confederate forces under Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow started construction of these two positions in April 1861, to block

Federal navigation of the Mississippi. When Leonidas Polk withdrew from Columbus, Ky., during the period February 29-March

2, 1862, in the preliminary moves of the Shiloh campaign, he sent the 5,000-man division of John P. McCown to reinforce the

2,000 then occupying these two river positions. On a peninsula 10 miles long by three miles wide the defenses consisted

of a two-regiment redoubt at New Madrid, and land batteries on a floating battery at Island No. 10. The latter was covered

by land batteries on the Tennessee shore. Federal forces had to reduce these forts in connection with their general offensive

down the Mississippi (the Henry-Donelson and Shiloh campaigns). Gen. Henry W. Halleck had sent some of John Pope's force

in central Missouri to reinforce Ulysses S. Grant's attack on Donelson; he also told Pope to organize a corps from the

remaining troops in Missouri and to capture New Madrid. Pope realized that the 50 heavy guns and the small fleet of gunboats

the Confederates had in and near the position necessitated a regular siege operation. He sent for siege artillery and

started a bombardment and the construction of approaches on March 13. On this same date McCown ordered the evacuation of New

Madrid and moved the garrison across the river to the peninsula in order to avoid being isolated. For this action he was

relieved of command and succeeded by William Mackall. Pope now decided to cross the river south of New Madrid and turn the

defense of Island No. 10. Since his supporting naval transports were upstream, he had a canal cut through the swamps so that

boats could by-pass the defenses of Island No. 10. The canal was finished on April 4. Two Federal gunboats ran the Confederate

batteries to support the river crossing, and on April 7 four regiments were ferried across the Mississippi to cut the Confederate

line of retreat at Tiptonville. According to Confederate records, Mackall surrendered 3,500 men (over 1,500 of whom were

sick) and 500 escaped through the swamps. The defeat of the Confederates opened the river for the capture of Memphis,

Tennessee two months later in the Battle of Memphis. Pope's victory opened the Mississippi to Fort Pillow, and gave him a

reputation which led to his being selected by Lincoln two months later to command the Army of Virginia (Second Bull Run

Campaign). (Island Number Ten has since disappeared as a result of erosion from the Mississippi River).

The Union and Confederate reports offer different perspectives for the Battle

of Island No. 10. Although the outcome was the same, the difference was noted in the number of men that surrendered.

The National Park Service, nevertheless, officially indicates the casualties as "unknown."

April 7, 1862 - Battle of Island No. 10. According to the Union Army report,

the battle was fought in and around Island Number Ten in the Mississippi River, near New Madrid, Missouri which was simultaneously

attacked. In order to continue down the Mississippi, the Union found that it had to capture the heavily defended island.

The Confederates fortifications consisted of land batteries on the island and a floating battery off the coast of the island.

On March 16, 1862, Union gunboats started shelling the island fortifications, while Confederates were returning fire from

land batteries. On April 4 at night, the gunboat USS Carondelet managed to pass by the island. On April 7, the USS Pittsburg

managed to join her. Then, under cover of these gunboats, Union troops under the command of Gen. John Pope crossed the Mississippi

River and landed below the island, crossing a Confederate withdrawal route. On April 7, 1862, the Confederate garrison, of

7,000 men surrendered. (The preceding total is almost certainly an exaggeration. Confederate records, although incomplete,

indicate that not more than 5,350 men were present.) The defeat of the Confederates, however, opened the river for the

capture of Memphis on June 6, 1862.

March 8-9, 1862 - Battle of Pea Ridge (aka Battle of Elkhorn Tavern).

The Battle of Pea Ridge occurred on March 8-9, 1862, at Pea Ridge in northwest Arkansas, near Bentonville. In the battle,

Union forces led by Brig. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis defeated Confederate troops under General Earl Van Dorn. The outcome of the

battle essentially cemented Union control of Missouri. Union forces in Missouri, during the latter part of 1861 and early

1862, had effectively pushed Confederate forces out of Missouri. By the spring of 1862 Union Brig. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis determined

to pursue the Confederates back into Arkansas with his Army of the Southwest. Curtis moved his approximately 10,250 Union

soldiers and 50 artillery pieces into Benton County, Arkansas along a small stream called Sugar Creek. Union forces consisted

primarily of soldiers from Iowa, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, and Ohio. Over half of the Federal army were German immigrants.

Curtis found an excellent defensive position on the north side of the creek and proceeded to fortify it and place artillery

for an expected Confederate assault from the south. Confederate Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn had been appointed overall commander

of the Trans-Mississippi District to quell a simmering conflict between competing generals Sterling Price of Missouri and

Brig. Gen. Ben McCulloch of Texas. Van Dorn's Army of the West totaled approximately 16,000 men including 800 Cherokee Indian

troops, Price's Missouri State Guard, Texas Rangers, and regular Confederate troops from Arkansas and Louisiana. Van Dorn

was aware of the Union movements into Arkansas and was intent on destroying Curtis's Army of the Southwest and reopening the

gateway into Missouri. Prelude: General Van Dorn did not wish to attack Curtis's entrenched position head on. On March 4 he

split his army into two divisions under Price and McCulloch and ordered them to march north along the Bentonville Detour with

the hopes of getting behind Curtis and cutting off his lines of communication. Van Dorn left his supply trains behind in order

to make better speed, a decision which would later prove to be a crucial one. The Confederates made an arduous three day forced

march down the Bentonville Cutoff from Fayetteville in the midst of a freezing storm. Many of the Confederate soldiers were

ill-equipped and barefoot and it was said that one could find the army by following the bloody footprints in the snow. The

Confederates arrived at their destination strung out along the road, hungry, and tired. Compounding the Confederate problems

was the late arrival of McCulloch which led Van Dorn to split his forces in two. Van Dorn ordered McCulloch to circle around

the western end of Pea Ridge, turn east along the south face and meet Price's division at Elkhorn Tavern. Van Dorn and

Price would travel east along the north face of the ridge, secure Elkhorn Tavern, and wait for McCulloch. These delays

allowed Curtis to begin repositioning his Army to meet the unexpected attack from his rear and get his forces between the

two wings of Van Dorn's forces. Left wing: McCulloch's troops consisted of Confederate troops under Brig. Gen. James McQueen

McIntosh and two divisions of Cherokee Indians under Brig. Gen. Albert Pike. McCulloch's troops swung westward around

Pea Ridge and plowed into elements of the Federal Army at a small village named Leetown where a fierce firefight erupted.

McCulloch and McIntosh were killed in action soon after the clash began and Colonel Louis Hébert was captured. These events

effectively shattered the command structure and the Confederates were unable to organize an effective attack in the resulting

chaos. Right wing: On the other side of Pea Ridge Van Dorn and Price encountered the Federals near Elkhorn Tavern. Van Dorn

ordered an attack and by nightfall the Confederates succeeded in pushing the Union forces back. They seized the Telegraph

and Huntsville Roads and succeeded in cutting Curtis's lines of communication at Elkhorn Tavern. The survivors from McCulloch's

command joined Van Dorn at the Tavern during the night. Federal counterattack: On the morning of March 8, Curtis massed

his artillery near the Tavern and launched a counterattack in an attempt to recover his supply lines. Leading the attack was

Curtis' second-in-command Franz Sigel. The massed artillery combined with cavalry and infantry attacks began to crumple

the Confederate lines. By noon Van Dorn realized that he was low on ammunition and that his supply trains were miles away

with no hope of arriving in time to resupply his men. Despite outnumbering his opponent, Van Dorn had no choice but to withdraw

down the Huntsville Road. Aftermath: Approximately 4,600 Confederates fell in battle at Pea Ridge including a large number

of officers. Federal forces suffered approximately 1,400 casualties. With the defeat

at Pea Ridge the Confederates never again seriously threatened the state of Missouri. Within weeks Van Dorn's army would be

transferred across the Mississippi River to bolster the Army of Tennessee leaving Arkansas virtually defenseless. With his

victory, Curtis proceeded to move farther into undefended Arkansas with the hope of capturing Little Rock. (See also

Arkansas Civil War History.)

| Map of Civil War Western Theater in 1863 |

|

| Map of Civil War and Western Theater in 1863 |

June 6, 1862 -

Capture of Memphis. The Battle of Memphis was a naval battle fought on the Mississippi River on June 6, 1862, resulting in

the Union fleet capturing the city of Memphis, Tennessee. After the Confederate River Defense Fleet, commanded by Capt.

James E. Montgomery and Brig. Gen. M. Jeff Thompson (Missouri State Guard), bested the Union ironclads at Plum Run Bend, Tennessee,

on May 10, 1862, they retired to Memphis. Confederate Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard ordered troops out of Fort Pillow and Memphis

on June 4, after learning of Union Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck's occupation of Corinth, Mississippi. Thompson's few troops,

camped outside Memphis, and Montgomery's fleet were the only force available to meet the Union naval threat to the city. From

Island No. 45, just north of Memphis, Flag-Officer Charles H. Davis and Col. Charles Ellet launched a naval attack on Memphis

after 4:00 am on June 6. Arriving off Memphis about 5:30 am, the battle began. In the hour and a half battle, the Union boats

sank or captured all but one of the Confederate vessels; General Earl Van Dorn escaped. Immediately following the battle,

Col. Ellet's son, Medical Cadet Charles Ellet, Jr., met the mayor of Memphis and raised the Union colors over the courthouse.

Later, Flag-Officer Davis officially received the surrender of the city from the mayor. The Indiana Brigade, commanded

by Col. G.N. Fitch, then occupied the city. Memphis, an important commercial and economic center on the Mississippi River,

had fallen, opening another section of the Mississippi River to Union shipping.

August 6-9, 1862 - Battle of Kirksville. Col. John McNeil and his troops,

numbering about 1,000, had been pursuing Col. Joseph C. Porter and his Confederate Missouri Brigade of 2,500 men for more

than a week. Before noon on August 6, McNeil attacked Porter in the town of Kirksville, where his men had hidden themselves

in homes and stores and among the crops in the nearby fields. After almost three hours of fighting, the Yankees secured the

town, captured numerous prisoners, and chased the others away. Three days later, another Union force met and finished the

work begun at Kirksville, destroying Porter’s command. Kirksville helped consolidate Union dominance in northeastern

Missouri. Estimated Casualties: 456 total (US 88; CS 368).

August 11, 1862 - Battle of Independence (aka First Battle of Independence).

On August 11, 1862, Col. J.T. Hughes’s Confederate force, including William Quantrill, attacked Independence, at dawn,

in two columns on different roads. They drove through the town to the Union Army camp, capturing, killing, and scattering

the Yankees. Lt. Col. James T. Buel, commander of the garrison, attempted to hold out in one of the buildings with some of

his men. Soon the building next to them was on fire, threatening them. Buel then, by means of a flag of truce, arranged a

meeting with the Confederate commander, Col. G.W. Thompson, who had replaced Col. J.T. Hughes, killed earlier. Buel surrendered

and about 150 of his men were paroled, the others had escaped, hidden, or been killed. Having taken Independence, the Rebel

force headed for Kansas City. Confederate dominance in the Kansas City area continued, but not for long. Estimated Casualties:

Total unknown (US approx. 344; CS unknown).

August 15-16, 1862 - Battle of Lone Jack. Maj. Emory S. Foster, under orders,

led an 800-man combined force from Lexington to Lone Jack. Upon reaching the Lone Jack area, he discovered 1,600 Rebels under

Col. J.T. Coffee and prepared to attack them. About 9:00 pm on the 15th, he and his men attacked the Confederate camp and

dispersed the force. Early the next morning, Union pickets informed Foster that a 3,000-man Confederate force was advancing

on him. Soon afterwards, this force attacked and a battle ensued that involved charges, retreats, and counterattacks. After

five hours of fighting and the loss of Foster, Coffee and his 1,500 men reappeared, causing Foster’s successor, Capt.

M.H. Brawner to order a retreat. The men left the field in good order and returned to Lexington. This was a Confederate victory,

but the Rebels had to evacuate the area soon afterward, when threatened by the approach of large Union forces. Except for

a short period of time during Price’s Raid, in 1864, the Confederacy lost its clout in Jackson County. Estimated Casualties:

270 total (US 160; CS 110).

September 30, 1862 - Battle of Newtonia (aka First Battle of Newtonia).

Following the Battle of Pea Ridge, in March 1862, most Confederate and Union troops left northwestern Arkansas and southwestern

Missouri. By late summer, Confederates returned to the area, which caused much apprehension in nearby Federally-occupied Springfield,

Missouri, and Fort Scott, Kansas. Confederate Col. Douglas Cooper reached the area on the 27th and assigned two of his units

to Newtonia where there was a mill for making breadstuffs. In mid-September, two brigades of Brig. Gen. James G. Blunt’s

Union Army of Kansas left Fort Scott for Southwest Missouri. On the 29th, Union scouts approached Newtonia but were chased

away. Other Union troops appeared in nearby Granby where there were lead mines, and Cooper sent some reinforcements there.

The next morning, Union troops appeared before Newtonia and fighting ensued by 7:00 am. The Federals began driving the enemy,

but Confederate reinforcements arrived, swelling the numbers. The Federals gave way and retreated in haste. As they did so,

some of their reinforcements appeared and helped to stem their retreat. The Union forces then renewed the attack, threatening

the enemy right flank. But newly arrived Confederates stopped that attack and eventually forced the Federals to retire again.

Pursuit of the Federals continued after dark. Union gunners posted artillery in the roadway to halt the pursuit. As Confederate

gunners observed the Union artillery fire for location, they fired back, creating panic. The Union retreat turned into a rout

as some ran all the way to Sarcoxie, more than ten miles away. Although the Confederates won the battle, they were unable

to maintain themselves in the area given the great numbers of Union troops. Most Confederates retreated into northwest Arkansas.

The 1862 Confederate victories in southwestern Missouri at Newtonia and Clark’s Mill were the South’s apogee in

the area; afterwards, the only Confederates in the area belonged to raiding columns. Estimated Casualties: 345 total (US 245;

CS 100).

| Map of Civil War Western Theater in 1864 |

|

| Map of Civil War and Western Theater in 1864 |

November 7, 1862 - Battle of Clark's Mill (aka Battle of Vera Cruz). Having

received reports that Confederate troops were in the area, Capt. Hiram E. Barstow, Union commander at Clark’s Mill,

sent a detachment toward Gainesville and he led another southeastward. Barstow’s men ran into a Confederate force, skirmished

with them and drove them back. His column then fell back to Clark’s Mill where he learned that another Confederate force

was coming from the northeast. Unlimbering artillery to command both approach roads, Barstow was soon engaged in a five-hour

fight with the enemy. Under a white flag, the Confederates demanded a surrender, and the Union, given their numerical inferiority,

accepted. The Confederates paroled the Union troops and departed after burning the blockhouse at Clark’s Mill. Clark’s

Mill helped the Confederates to maintain a toehold in southwest Missouri. Estimated Casualties: Total unknown (US 113; CS

unknown).

January 8, 1863 - Battle of Springfield (aka Second Battle of Springfield).

Brig. Gen. John S. Marmaduke’s expedition into Missouri reached Ozark, where it destroyed the Union post, and then approached

Springfield on the morning of January 8, 1863. Springfield was an important Federal communications center and supply depot

so the Rebels wished to destroy it. The Union army had constructed fortifications to defend the town. Their ranks, however,

were depleted because Francis J. Herron’s two divisions had not yet returned from their victory at Prairie Grove on

December 7. After receiving a report on January 7 of the Rebels’ approach, Brig. Gen. Egbert B. Brown set about preparing

for the attack and rounding up additional troops. Around 10:00 am, the Confederates advanced in battle line to the attack.

The day included desperate fighting with attacks and counterattacks until after dark, but the Federal troops held and the

Rebels withdrew during the night. Brown had been wounded during the day. The Confederates appeared in force the next morning

but retired without attacking. The Federal depot was successfully defended, and Union strength in the area continued. Estimated

Casualties: 403 total (US 163; CS 240).

January 9-11, 1863 - Battle of Hartville. John S. Marmaduke led a Confederate

raid into Missouri in early January 1863. This movement was two-pronged. Col. Joseph C. Porter led one column, comprising

his Missouri Cavalry Brigade, out of Pocahontas, Arkansas, to assault Union posts around Hartville, Missouri. When he neared

Hartville, on January 9, he sent a detachment forward to reconnoiter. It succeeded in capturing the small garrison and occupying

the town. The same day, Porter moved on toward Marshfield. On the 10th, some of Porter’s men raided other Union installations

in the area before catching up with Marmaduke’s column east of Marshfield. Marmaduke had received reports of Union troops

approaching to surround him and prepared for a confrontation. Col. Samuel Merrill, commander of the approaching Union column,

arrived in Hartville, discovered that the garrison had already surrendered and set out after the Confederates. A few minutes

later, fighting began. Marmaduke feared being cut off from his retreat route back to Arkansas so he pushed Merrill’s

force back to Hartville, where it established a defense line. Here, a four-hour battle ensued in which the Confederates suffered

many casualties but compelled the Yankees to retreat. Although they won the battle, the Confederates were forced to abandon

the raid and return to friendly territory. Estimated Casualties: 407 total (US 78; CS 329).

April 26, 1863 - Battle of Cape Girardeau (aka Battle of Cape Girardeau

City). Brig. Gen. John S. Marmaduke sought to strike Brig. Gen. John McNeil, with his combined force of about 2,000 men, at

Bloomfield, Missouri. McNeil retreated and Marmaduke followed. Marmaduke received notification, on April 25, that McNeil was

near Cape Girardeau. He sent troops to destroy or capture McNeil’s force, but then he learned that the Federals had

placed themselves in the fortifications. Marmaduke ordered one of his brigades to make a demonstration to ascertain the Federals’

strength. Col. John S. Shelby’s brigade made the demonstration which escalated into an attack. Those Union forces not

already in fortifications retreated into them. Realizing the Federals’ strength, Marmaduke withdrew his division to

Jackson. After finding the force he had been chasing, Marmaduke was repulsed. Meant to relieve pressure on other Confederate

troops and to disrupt Union operations, Marmaduke’s expedition did little to fulfill either objective. Estimated Casualties:

337 total (US 12; CS 325).

| 1864 Price's Raid Map |

|

| Map of Price's Raid in 1864 |

September 19-October 28, 1864 - Price's Missouri Raid. From January through August small skirmishes

and guerrilla activity had unsettled Missouri. In late summer Confederate General Sterling Price was ordered to lead

a raid on the state. Price's initial goal was St. Louis, but he delayed at Pilot Knob to attack a small contingent of Union

soldiers led by General Thomas Ewing, Jr. The Federals barricaded themselves inside Ft. Davidson, an earthwork fortification

in the Arcadia Valley. Expecting a quick victory, General Price's army was hurt badly in series of headlong assaults

on September 27. Remarkably, the Federals escaped by making a forced march to Leasburg and Rolla. The delay cost Price an

opportunity to attack St. Louis, so he turned west to install a Confederate governor in Jefferson City. The Confederate raiders

discovered that the capitol was stoutly defended, and after their losses at Ft. Davidson the Confederates decided an attack

was unwise. The 10,000-man raid advanced into the most pro-Confederate portion of the state, the western Missouri River valley.

To forage better General Price divided his army and they fanned out across west central Missouri moving toward Kansas.

This portion of the raid was marked by victories over small Federal detachments at Sedalia and Warrensburg. The Confederate

raiders captured a Federal supply depot and steamboat, after some significant fighting, at Glasgow on October 15. As Price's

army slowed to forage, the Federals mounted a vigorous pursuit from the east led by General William S. Rosecrans.

In Kansas, General Curtis and General James Blunt rallied the militia in defense of the Sunflower

State. Without realizing it General Price was slowly being squeezed between two Union armies. The slow moving Confederates

finally collided with General Blunt's Kansas militiamen at Lexington on October 19, but Shelby's Iron Brigade, of Price's

army, forced General Blunt to retreat. The two armies clashed again at the Little Blue River on October 21 and in the main

square of Independence the next day. Each time General Blunt was compelled to fall back. The Kansans tried to establish

a defensive line along the Big Blue River at Byram's Ford on October 22, but the result was the same with the Union men

routed, and in retreat to the town of Westport. The Confederates retreated south of Westport and awaited the Federals next

move. On a cold October 23 morning they were attacked by the Federals, led by Generals Blunt and Curtis. After severe

fighting at close range the Southern line gave way only to be saved by a series of stubborn rearguard actions by General Shelby's

men. General Price decided to head for Indian Territory and save his large, ponderous wagon train. While Generals Shelby and

Price were pushing westward, Generals James Fagan and John S. Marmaduke were struggling to fight a strong rearguard action

against General Rosecran's Federals advancing from the east. The Southerners fought a significant delaying action on October

23 at Byram's Ford on the Big Blue River where the previous day General Price's portion of the army had forged across the

river. They had no better luck than Shelby and Price at Westport, and were forced to join the Southern retreat. A small

pause by the Federal pursuers allowed General Price to gain a modest advantage in his retreat. Unwilling to follow the advice of

his subordinates General Price refused to burn his wagons, and use the time gained to make good his escape. Instead, the slow

moving Confederate rear guard was attacked at the small village of Trading Post (aka Battle of Battle of Marais

de Cygnes or Battle of Osage), on October 25, just across the Missouri border into Kansas. Later that afternoon, the

steep crossing of Mine Creek slowed the bulk of Price's army. The Confederates were greeted in Kansas with an artillery bombardment,

that began at 4:00 am, and Union cavalry. Attacked by Federal cavalry just north of the Mine Creek crossing General

Price's army could not halt the charge, and his army disintegrated only to be saved by General Shelby's Iron Brigade. Once

reorganized, General Price burned the bulk of his wagons, and struggled through Missouri. General Shelby's troopers stopped

the Federal pursuit with a running fight at Newtonia on October 28. The Confederates limped back into Arkansas and Texas

defeated and demoralized.

Needing to avoid Fort Smith, Arkansas, Price swung west into Indian Territory

and Texas before returning to Arkansas on December 2 with only 6,000 survivors from an original force of 12,000, including

thousands of guerrillas who joined him later. He reported to Kirby Smith that he "marched 1,434 miles, fought 43 battles and

skirmishes, captured and paroled over 3,000 Federal officers and men, captured 18 pieces of artillery ... and destroyed Missouri

property ... of $10,000,000 in value." Price's actions had caused the Union army to spend resources and manpower that

it could easily replace, but, on the other hand, the Confederates couldn't afford to lose a single man. Nevertheless,

Price's mission had been a failure and contributed, along with Union successes in Virginia and Georgia, to the re-election

of President Lincoln. Price, consequently, had completed the Union's task: he cleared Missouri of the Guerrillas,

and many who joined him were either killed or vacated the state with him. Price's Raid proved to be the final Confederate

offensive in the Trans-Mississippi region during the war.

1865 - Guerrillas. Although the war was practically over in late

1865, fragmentary bands of guerrillas — remnants of Price's army of the preceding year — continued to infest some

portions of the state, and the militia was kept in service for some time after hostilities elsewhere had entirely ceased.

Thus Missouri was one of the last as well as one of the first states to feel the curse of civil war. During the contest she

furnished to the Federal government a total of 109,111 men, exclusive of the militia she maintained

to keep peace within her borders and protect her people from the raids of the guerrillas, jayhawkers and other predatory bands

who were actuated more by the prospect of plunder than by principles or patriotism. On July 21, 1865, in the market square of Springfield, Missouri, James Butler ("Wild Bill") Hickok shoots Dave Tutt dead in what is regarded as the first true western showdown.

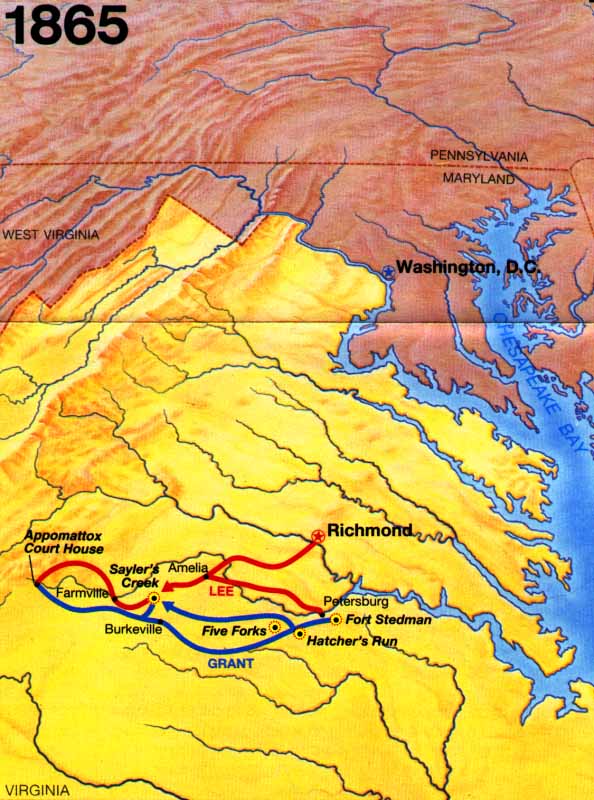

| Map of Civil War Western Theater in 1865 |

|

| Map of Civil War and Western Theater in 1865 |

| Civil War in 1865 |

|

| 1865 Appomattox Campaign Map |

April 1-9, 1865 - The Appomattox Campaign. The Confederate retreat began

on April 1 southwestward as Robert E. Lee sought to use the still-operational Richmond & Danville Railroad. At its western

terminus at Danville he would unite with Gen. Joseph E. Johnston's army, which was retiring up through North Carolina. Taking

maximum advantage of Danville's hilly terrain, the two Southern forces would make a determined stand against the converging

armies of Ulysses S. Grant and Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman. But Grant moved too fast for the plan to materialize, and Lee

waited 24 hours in vain at Amelia Court House for trains to arrive with badly needed supplies. Federal cavalry, meanwhile,

sped forward and cut the Richmond & Danville at Jetersville. Lee had to abandon the railroad, and his army stumbled across

rolling country in an effort to reach Lynchburg, another supply base that could be defended. Union horsemen seized the vital

rail junction at Burkeville as Federal infantry continued to dog the Confederates. On April 6 almost one-fourth of Lee's army

was trapped and captured at Sayler's Creek. Lee, at Farmville. Most surrendered, including Confederate generals Richard S.

Ewell, Barton, Simms, Joseph B. Kershaw, Custis Lee, Dubose, Eppa Hunton, and Corse. This action was considered the death

knell of the Confederate army. Upon seeing the survivors streaming along the road, Lee exclaimed "My God, has the army dissolved?"

Lee led his remaining 30,000 men in a north-by-west arc across the Appomattox River and toward Lynchburg. In the meantime,

Grant, with four times as many men, sent Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan's cavalry and most of two infantry corps on a hard,

due-west march from Farmville to Appomattox Station. Reaching the railroad first the Federals blocked Lee's only line of advance.

April 9, 1865 - Surrender at Appomattox. Early on April 9, the remnants

of John B. Gordon's corps and Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry formed a line of battle at Appomattox Court House. Gen. Robert E. Lee

determined to make one last attempt to escape the closing Union pincers and reach his supplies at Lynchburg. At dawn the Confederates

advanced, initially gaining ground against Philip H. Sheridan's cavalry. The arrival of Union infantry, however, stopped the

advance in its tracks. Lee's army was now surrounded on three sides. Lee's options were gone. That afternoon, Palm Sunday,

Lee met Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in the front parlor of Wilmer McLean's home to discuss peace terms. After

agreeing terms, Lee surrendered his army. The actual surrender of the Confederate Army occurred April 12, an overcast Wednesday.

As Southern troops marched past silent lines of Federals, a Union general noted "an awed stillness, and breath-holding, as

if it were the passing of the dead." Grant issued a brief statement: "The war is over; the rebels are our countrymen again

and the best sign of rejoicing after the victory will be to abstain from all demonstrations in the field." Grant allows Rebel

officers to keep their sidearms and permits soldiers to keep horses and mules. Lee tells his troops: "After four years of

arduous service marked by unsurpassed courage and fortitude the Army of Northern Virginia has been compelled to yield to overwhelming

numbers and resources".

April 10, 1865 - Celebrations break out in Washington D.C. (known as Washington

City at the time).

April 14, 1865 - Assassination of Lincoln. The Stars and Stripes is ceremoniously

raised over Fort Sumter. That night, Abraham Lincoln and his wife Mary see the play "Our American Cousin" at Ford's Theater.

At 10:13 p.m., during the third act of the play, John Wilkes Booth shoots the president in the head. As he leaps to the stage

(breaking a shinbone), Booth shouts, Sic Semper Tyrannis (Thus Always to Tyrants). Doctors attend to the president in the

theater then move him to a house across the street. He never regains consciousness. Abraham Lincoln died the next morning

(April 15) at 7:22 a.m. in the Petersen Boarding House. He was 56 years old. Vice President Andrew Johnson assumes the presidency.

Secretary of State William H. Seward was stabbed in his Washington home on April 14, 1865, the same night President Lincoln

was shot in the Ford Theater. The attacker, Louis Powell, a co-conspirator with Booth, injured five people in the nighttime

action. Seward recovered from his injuries and continued to serve as Secretary of State for President Andrew Johnson.

April 18, 1865 - Surrender of Johnston. Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnston

in North Carolina succeeds in delaying the advance of General William T. Sherman at Bentonville in March. But lack of men

and supplies forced Johnston to order continued withdrawal, and he surrendered to Sherman at Durham Station, N.C., on April

26.

| 1865 Civil War Map of Battlefields |

|

| Map of Civil War Battles in 1865 |

April 26, 1865 - John Wilkes Booth Killed. Union cavalry corner John Wilkes

Booth in a tobacco barn in Bowling Green, Virginia. Cavalryman Boston Corbett shoots the assassin dead.

April 27, 1865 - Sinking of the Sultana. The steamboat Sultana, carrying

2,300 passengers, explodes and sinks in the Mississippi River, killing 1,700. Most were Union survivors of the Andersonville

Prison.

May 4, 1865 - Burial of Lincoln. Abraham Lincoln is laid to rest in Oak

Ridge Cemetery, outside Springfield, Illinois.

May 4, 1865 - Surrender of Taylor. Confederate General Richard Taylor, commanding

all Confederate forces in Alabama, Mississippi, and eastern Louisiana, surrenders his forces to Union General Edward Canby

at Citronelle, Alabama.

May 5, 1865 - First Train Robbery in U.S. In North Bend, Ohio (a suburb

of Cincinnati), the first train robbery in the United States takes place. About a dozen men tore up tracks to derail an Ohio

& Mississippi train that had departed from Cincinnati. (Some reports identify the train as belonging to the Union Pacific

Railroad). More than 100 passengers were robbed at gunpoint of cash and jewelry. The robbers then blew open safes of the Adams

Express Co. that were said to contain thousands of dollars in U.S. bonds. The robbers fled across the Ohio River into Kentucky.

Lawrenceburg, Indiana officials were notified by telegraph of the robbery and in turn notified military authorities. Troops

were sent to hunt down the robbers. The outlaws were traced through Verona, Kentucky, but were never captured.

May 10, 1865 - Capture of Jefferson Davis. Jefferson Davis, president of

the Confederacy, fleeing to Georgia, is captured on May 10 and imprisoned at Fortress Monroe, on the coast of Virginia, on

May 19. Davis was indicted for treason in May 1866, but in 1867 he was released on bail which was posted by prominent citizens

of both northern and southern states, including Horace Greeley and Cornelius Vanderbilt who had become convinced he was being

treated unfairly. He visited Canada, and sailed for New Orleans, Louisiana, via Havana, Cuba. In 1868, he traveled to Europe.

That December, the court rejected a motion to nullify the indictment, but the prosecution dropped the case in February of

1869.

May 12-13, 1865 - Battle of Palmito Ranch was fought on May 12-13, 1865,

and in the kaleidoscope of events following the surrender of Robert E. Lee's army, was nearly ignored. It was the last major

clash of arms in the war. Early in 1865, both sides in Texas agreed to a gentlemen's agreement that there was no point to

further hostilities. Why the needless battle even happened remains something of a mystery—perhaps Union Colonel Theodore

H. Barrett had political aspirations (he certainly had little military experience). Barrett instructed Lieutenant Colonel

David Branson to attack the rebel encampment at Brazos Santiago Depot near Fort Brown outside Brownsville. By that time, most

Union troops had pulled out from Texas for campaigns in the east. The Confederates were concerned to protect what ports they

had for cotton sales to Europe, as well as importation of supplies. Mexicans tended to side with the Confederates due to a

lucrative smuggling trade. Union forces marched upriver from Brazos Santiago to attack the Confederate encampment, and were

at first successful but were then driven back by a relief force. The next day, the Union attacked again, again to initial

success and later failure. Ultimately, the Union retreated to the coast. There were 118 Union casualties. Confederate casualties

were "a few dozen" wounded, none killed. Nothing was really gained on either side; like the war's first big battle (First

Bull Run to the Union, First Manassas to the Confederates), it is recorded as a Confederate victory. It is worth noting that

private John J. Williams of the 34th Indiana Volunteer Infantry was the last man killed at the Battle at Palmito Ranch, and

probably the last of the war. Fighting were white, African, Hispanic and native troops. Reports of shots from the Mexican

side are unverified, though many witnesses reported firing from the Mexican shore.

May 23-24, 1865 - Grand Review in Washington, D.C. Over a two-day period

in Washington, D.C., the immense, exultant victory parade of the Union's main fighting forces in many ways brought the Civil

War to its conclusion. The parade's first day was devoted to George G. Meade's force, which, as the capital's defending army,

was a crowd favorite. May 23 was a clear, brilliantly sunny day. Starting from Capitol Hill, the Army of the Potomac marched

down Pennsylvania Avenue before virtually the entire population of Washington, a throng of thousands cheering and singing

favorite Union marching songs. At the reviewing stand in front of the White House were President Andrew Johnson, General-in-Chief

Ulysses S. Grant, and top government officials. Leading the day's march, General Meade dismounted in front of the stand and

joined the dignitaries to watch the parade. His army made an awesome sight: a force of 80,000 infantrymen marching 12 across

with impeccable precision, along with hundreds of pieces of artillery and a seven-mile line of cavalrymen that alone took

an hour to pass. One already famous cavalry officer, George Armstrong Custer, gained the most attention that day-either by

design or because his horse was spooked when he temporarily lost control of his mount, causing much excitement as he rode

by the reviewing stand twice. The next day was William T. Sherman's turn. Beginning its final march at 9 a.m. on another beautiful

day, his 65,000-man army passed in review for six hours, with less precision, certainly, than Meade's forces, but with a bravado

that thrilled the crowd. Along with the lean, tattered, and sunburnt troops was the huge entourage that had followed Sherman's

on his march to the sea: medical workers, laborers, black families who fled from slavery, the famous "bummers" who scavenged

for the army's supplies, and a menagerie of livestock gleaned from the Carolina and Georgia farms. Riding in front of his

conquering force, Sherman later called the experience "the happiest and most satisfactory moment of my life." For the thousands

of soldiers participating in both days of the parade, it was one of their final military duties. Within a week of the Grand

Review, the Union's two main armies were both disbanded.

May 26, 1865 - Surrender of Kirby Smith. General Kirby Smith, with 43,000

soldiers, surrenders to Gen. Edward Canby in Shreveport, Louisiana.

May 29, 1865 - Amnesty Proclamation. Andrew Johnson presents his "restoration"

plan, which is at odds with Congress' reconstruction plan. He also announces a general pardon for everyone involved in the

"rebellion," except for a few Confederate leaders.

June 23, 1865 - Surrender of Stand Watie. At Fort Towson in the Choctaw

Nations' area of Oklahoma Territory, Brig. Gen. Stand Watie surrendered the last significant rebel army, becoming the last

Confederate general in the field to surrender.

July 5, 1865 - Secret Service Established. The Secret Service was commissioned

on July 5, 1865 in Washington, D.C., to suppress counterfeit currency, which is why it was established under the United States

Department of the Treasury. After the assassination of President William McKinley in 1901, Congress informally requested Secret

Service presidential protection. A year later, the Secret Service assumed full-time responsibility for protection of the President.

July 5, 1865 - William Booth founds the Christian Mission (later renamed

to the Salvation Army).

July 21, 1865 - In the market square of Springfield, Missouri, James Butler

("Wild Bill") Hickok shoots Dave Tutt dead in what is regarded as the first true western showdown.

August 2, 1865 - Surrender of the Shenandoah. C.S.S. Shenandoah learns the

war is over The captain and crew of the C.S.S. Shenandoah, still prowling the waters of the Pacific in search of Yankee whaling

ships, is finally informed by a British vessel that the South has lost the war. The Shenandoah sails from the northern Pacific

all the way to Liverpool, England, without stopping at any ports. Arriving on November 6, Capt. James I. Waddell surrendered

his ship to British officials.

October 10, 1865 - First Petroleum Pipeline. The first successful metal

pipeline was completed in 1865 and transported 80 barrels per hour of crude oil over a 5 mile route in Western Pennsylvania.

Samuel Van Syckel, an oil buyer, began construction on a two-inch wide pipeline designed to span the distance to the railroad

depot five miles away. The teamsters, who had previously transported the oil, didn't take to kindly to Syckel's plan, and

they used pickaxes to break apart the line. Eventually Van Syckel brought in armed guards, finished the pipeline, and made

a ton-o-money. By 1865 wooden derricks were bled 3.5 million barrels a year out of the ground. Such large scale production

caused the price of crude oil to plummet to ten cents a barrel.

October 14, 1865 - Treaty with the Southern Cheyenne. The Southern Cheyenne

chiefs sign a treaty agreeing to cede all the land they formerly claimed as their own, most of Colorado Territory, to the

U.S. government. This was the desired end of the Sand Creek massacre.

November 10, 1865 - Execution of Capt. Wirz. Confederate Capt. Henry Wirz,

commandant of Andersonville, Georgia, prison camp, was tried by a military commission presided over by General Lew Wallace

from August 23 to October 24, 1865. Accused of ordering prisoners shot on sight, of sending bloodhounds after escaped prisoners,

and injecting prisoners with deadly vaccines, Wirz is convicted and hanged on November 10, 1865 for war crimes.

November 18, 1865 - Mark Twain published "Jim Smiley and his Jumping Frog"

in the New York Saturday Press. The story was immediately picked up nationally and then internationally, giving Twain his

first fame and the centerpiece for his first book "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, and Other Sketches."

| Missouri in the Civil War |

|

| High Resolution Missouri Map |

November 24, 1865 - Black Code Enacted in Mississippi. Mississippi becomes

the first state to establish a system of black codes to sharply limit the rights of freed blacks. Black codes have been described

thus: "Negroes must make annual contracts for their labor in writing; if they should run away from their tasks, they forfeited

their wages for the year. Whenever it was required of them they must present licenses (in a town from the mayor; elsewhere

from a member of the board of police of the beat) citing their places of residence and authorizing them to work. Fugitives

from labor were to be arrested and carried back to their employers. Five dollars a head and mileage would be allowed such

negro catchers. It was made a misdemeanor, punishable with fine or imprisonment, to persuade a freedman to leave his employer,

or to feed the runaway. Minors were to be apprenticed, if males until they were twenty-one, if females until eighteen years

of age. Such corporal punishment as a father would administer to a child might be inflicted upon apprentices by their masters.

Vagrants were to be fined heavily, and if they could not pay the sum, they were to be hired out to service until the claim

was satisfied. Negroes might not carry knives or firearms unless they were licensed so to do. It was an offence, to be punished

by a fine of $50 and imprisonment for thirty days, to give or sell intoxicating liquors to a negro. When negroes could not

pay the fines and costs after legal proceedings, they were to be hired at public outcry by the sheriff to the lowest bidder....

"In South Carolina persons of color contracting for service were to be known as "servants," and those with whom they contracted,

as "masters." On farms the hours of labor would be from sunrise to sunset daily, except on Sunday. The negroes were to get

out of bed at dawn. Time lost would be deducted from their wages, as would be the cost of food, nursing, etc., during absence

from sickness. Absentees on Sunday must return to the plantation by sunset. House servants were to be at call at all hours

of the day and night on all days of the week. They must be "especially civil and polite to their masters, their masters' families

and guests," and they in return would receive "gentle and kind treatment." Corporal and other punishment was to be administered

only upon order of the district judge or other civil magistrate. A vagrant law of some severity was enacted to keep the negroes

from roaming the roads and living the lives of beggars and thieves." The Black Codes outraged public opinion in the North

because it seemed the South was creating a form of quasi-slavery to evade the results of the war. President Andrew Johnson

supported the Black Codes, but the Radical Republicans who controlled Congress resisted furiously. They were never put into

effect in any state. Instead Congress passed the Civil Rights law of 1866. Congress also passed the Fourteenth Amendment to

the United States Constitution, but Johnson blocked it. After winning large majorities in the 1866 elections, the Republicans

put the South under military rule, and held new elections in which the Freedmen could vote. The new governments repealed all

the Black Codes, and they were never reenacted.

December 1, 1865 - Habeas Corpus Restored. The Writ of Habeas Corpus is

restored.

December 6, 1865 - The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution,

passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, by the House on January 31, 1865, and ratified on December 6, 1865, abolished slavery

as a legal institution. The Constitution, although never mentioning slavery by name, refers to slaves as "such persons" in

Article I, Section 9 and "a person held to service or labor" in Article IV, Section 2. The Thirteenth Amendment, in direct

terminology, put an end to this. The amendment states: "Section 1: Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a

punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place

subject to their jurisdiction. Section 2: Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation." The

thirteenth amendment to the Constitution of the United States was proposed to the legislatures of the several States by the

38th Congress, on the January 31, 1865, and was declared, in a proclamation of the Secretary of State of December 18, 1865,

to have been ratified by the legislatures of twenty-seven of the thirty-six States. Ratification was completed on December

6, 1865, with the vote to ratify in Georgia.

December 24, 1865 - The Ku Klux Klan is founded in Pulaski, Tenn. Confederate

Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest is appointed the first Grand Wizard. In its original incarnation, the Ku Klux Klan sought to protect

Whites in the South from dangers both real and imagined, and opposed the reforms enforced on the South by federal troops regarding

the treatment of former slaves, often using violence to achieve its goals. The first Klan was destroyed by President Ulysses

S. Grant's vigorous action under the Klan Act and Enforcement Act of 1871.

Sources: National Park Service; Official Records of the Union and Confederate

Armies; National Archives; Library of Congress; US Census Bureau; The Union Army (1908); Fox, William F. Regimental Losses

in the American Civil War (1889); Dyer, Frederick H. A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion (1908); Hardesty, Jesse. Killed

and died of wounds in the Union army during the Civil War (1915): Wright-Eley Co.; United States Army

Center of Military History; publications.usa.gov.

|

|

|