|

|

Civil War Charleston and the Citadels of the Sea

In Defense of Charleston: The Coastal Defenses

Coastal Defenses

Inventions and innovations employed in the Charleston area during the Civil War (1861-1865)

would usher onto the world stage a new era of warfare.

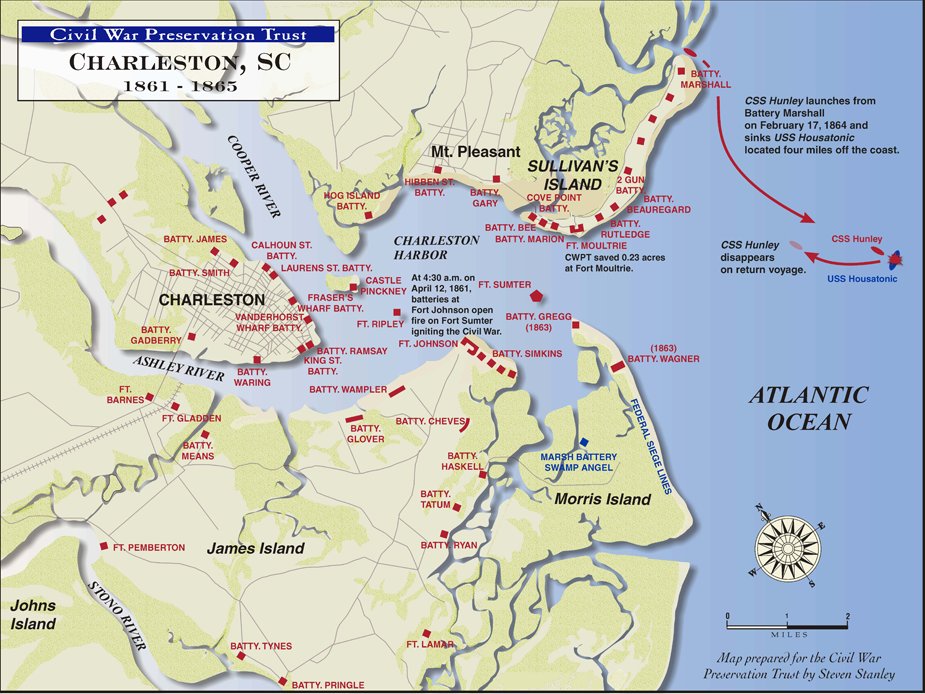

The Civil War defenses of Charleston consisted of a system of defensive

perimeters around the port city of Charleston from 1861 to 1865. Three of the structures were permanent fortifications constructed

in the early nineteenth century, but most of the structures were field works constructed by slaves between 1861 and 1865.

There were seventy-two major defensive positions and structures protecting Charleston during the Civil War. Excluding Fort

Sumter, Fort Moultrie, and Castle Pinckney, these batteries were all constructed of earth.

The field works defending Charleston varied in size from small one—gun

batteries for field pieces to large positions covering several acres and mounting twenty or more heavy siege cannons. Although

the more complex batteries included such details as powder magazines, bombproofs, covered ways, and sunken batteries, virtually

every work followed the basic plans of the post-Napoleonic period and utilized common profile elements. These plans included

a ditch which acted as an obstacle to attackers, a parapet which used the earth from the ditch for protective relief, a terreplein

or gun platform, and an embrasure in the parapet for cannons to fire. More specialized profile elements occurred in many heavy

batteries, and all were derived from the European practices of military engineering.

Charleston‘s defensive works followed the practice taught at West

Point, which included natural obstacles such as impassable marshes, river bends, and the mouths of estuaries carefully utilized

to place the attacking party at a disadvantage and to protect isolated positions. Batteries were also skillfully situated

in combination to provide crossing fields of fire, particularly in defense against naval attack. Fort Sumter, named in

honor of General Thomas Sumter, Revolutionary War hero, was built following the War of 1812, as one of a series of fortifications

on the Southern U.S. coast. Fort Sumter, the last bastion of resistance, was finally abandoned after the evacuation of Charleston

in February 1865.

| Civil War Charleston |

|

| Charleston and the Coastal Defenses |

|

|

|

|

|

Defending Charleston

General Robert E. Lee was appointed to the command of the South Carolina

coastal defenses in November 1861. Lee‘s responsibility from then until March 1862 resulted in the adoption of an overall

plan that stressed the use of earthworks and fortified defensive positions out of the range of heavy naval batteries.

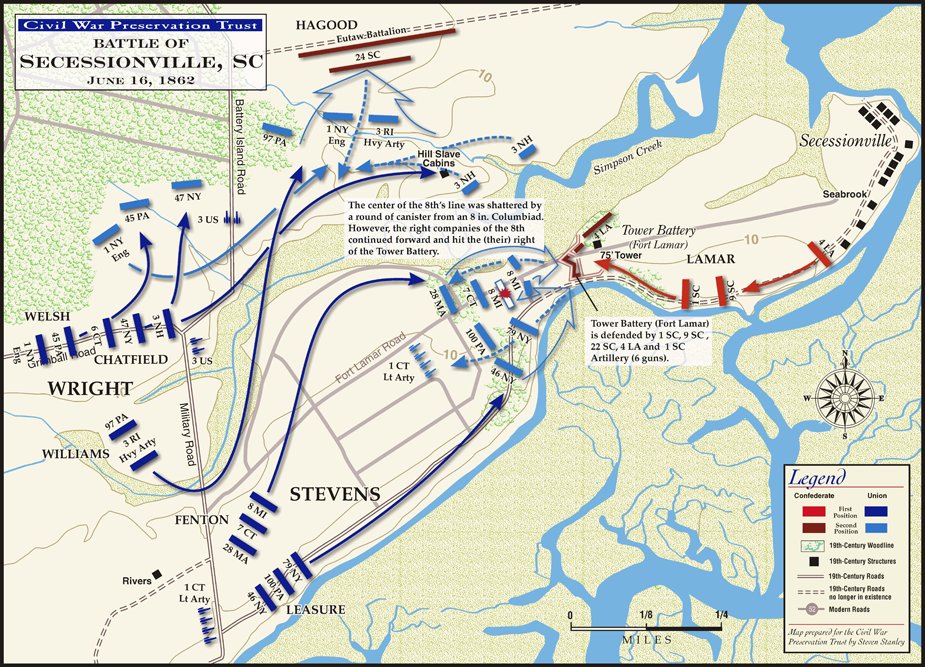

General J. C. Pemberton assumed command of the Charleston defenses from

March 1862 to August 1862. Pemberton abandoned the Cole's Island fortifications at the mouth of the Stono River, which opened

James Island and Morris Island to amphibious assault by the Federal forces. In June 1862 a Federal force landed on James Island

and advanced against the earthworks which General Pemberton was erecting. An assault on Fort Lamar at Secessionville on June

16 was repulsed.

| Battle of Secessionville Map |

|

| Battle of Secessionville |

General Beauregard was recalled to Charleston in August 1862,

and he immediately strengthened and redefined the defensive perimeter. Beauregard's defenses included, in addition to the

harbor and field fortifications, torpedoes, mines, harbor obstructions, and inonclad gunboats. On January 30, 1863, two Confederate

gunboats, the Chicora and the Palmetto State, temporarily drove off the blockading fleet.

In January 1863 a large Federal fleet under the command of Du Pont, including

the ironclad warship New Ironsides and four ironclad Monitor-class warships, was ordered to assault Charleston. This fleet

made its assault on April 7, bombarding the harbor defenses and attempting to establish a land assault. Fort Sumter and Fort

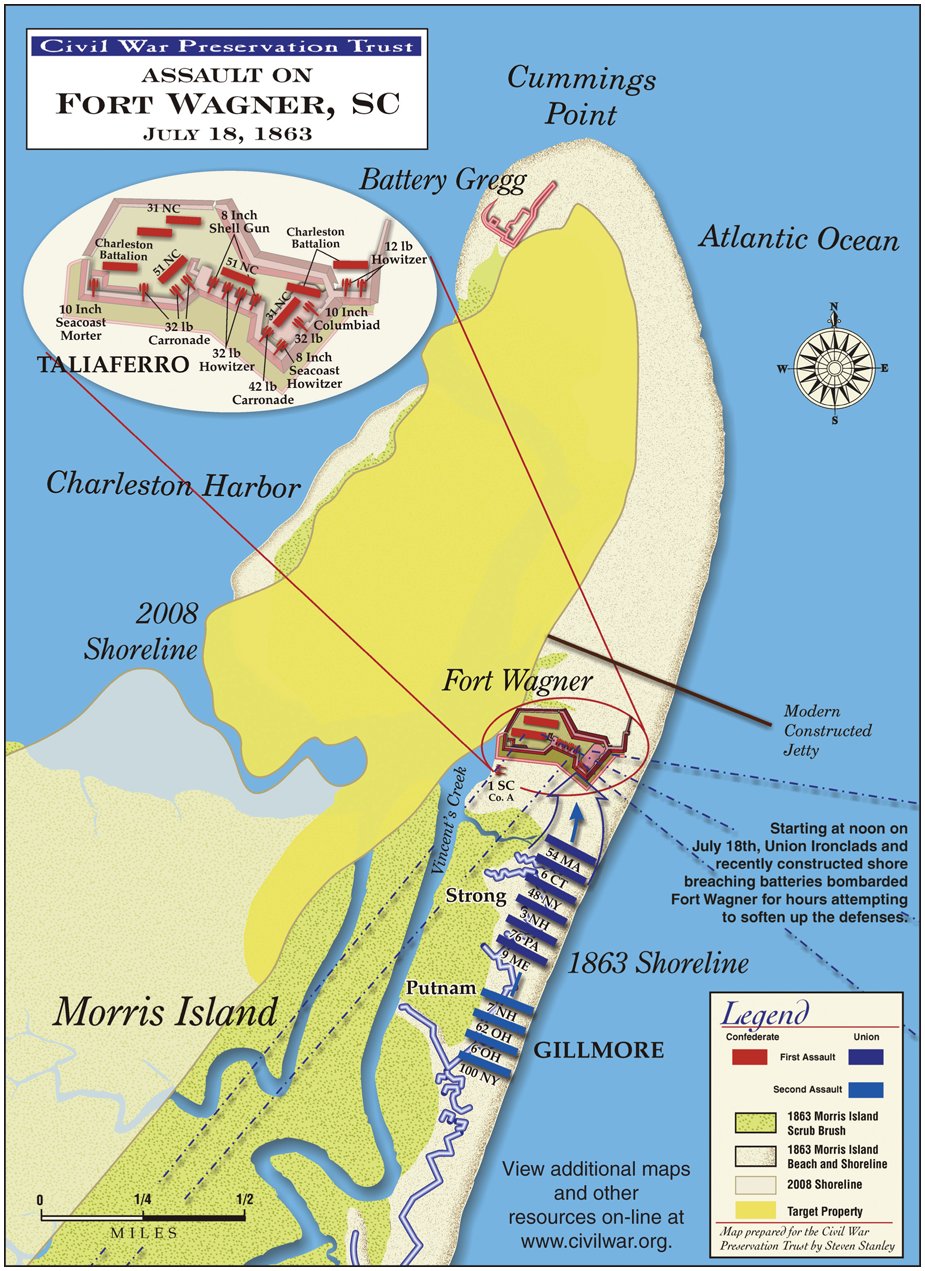

Moultrie bore the brunt of this attack. The attack was repulsed, with heavy damage to the invading fleet. In July 1863 a new

assault under the command of Brigadier General Q. A. Gillmore and Admiral Dahlgren was launched. This assault sought to capture

Fort Wagner on Morris Island.

After the July 11 assault on Fort Wagner

failed, Gillmore reinforced his beachhead on Morris Island. At dusk July 18, Gillmore launched an attack spearheaded by the

54th Massachusetts Infantry, an all black volunteer regiment led by white officers. The unit’s colonel, Robert

Gould Shaw, was killed. Members of the Union brigade scaled the parapet but after brutal hand-to-hand combat were repulsed

with heavy casualties. The Federals resorted to siege operations to reduce the fort. This was the fourth time in the war that

black troops played a crucial combat role, proving to skeptics that they would fight bravely if only given the opportunity.

| Assault on Battery Wagner |

|

| Assault on Fort Wagner, aka Battery Wagner |

Diversionary attacks on James Island and a continuous naval bombardment

against Fort Wagner and the harbor defenses were included. After a fifty-eight day assault,

Fort Wagner was evacuated on September 7. Morris Island served as a base for the continuing Federal siege on Charleston, including

its use of the legendary Swamp Angel. Federal batteries on Morris Island began bombarding the harbor forts

and the city proper. On September 8 an amphibious assault on Fort Sumter was repulsed. The land and naval bombardment of the

defensive positions continued through the year. The Confederate defenders utilized numerous tactics to stymie the assault,

including torpedoes, rams and the submarine Hunley, which on February 17, 1864, sank the Federal sloop Housatonic. In June

1864 a new amphibious assault on the James Island defensive line was repulsed. An amphibious assault on Fort Johnson on July

2—3 was also repulsed. At the same time, a concentrated naval assault on the James Island defenses, especially Fort

Pringle, was begun; this assault lasted eight days before it was terminated. The land and naval bombardment of the defenses

and the city itself were intensified through the year. On December 21, 1864, Savannah was evacuated in the face of General

William T. Sherman's advancing troops. The Federal forces besieging Charleston intensified their assaults. The advance of

General Sherman demanded that Charleston be evacuated, and on February 17, 1865, the Confederate defenders left the city.

| Fort Sumter, South Carolina |

|

| View of Fort Sumter ruins in 1865 from a sandbar |

Conclusion

Both the Confederate and the Federal governments realized the strategic importance of the

port of Charleston. General Beauregard organized the defense of the city to repel attack from five different routes: land

attack through Christ Church Parish north of Charleston; land attack from the south through St. Andrew's Parish to capture

the city from the rear; combined land and naval attack through James Island; combined land and naval attack through Sullivan's

Island and the harbor; combined land and naval attack through Morris Island.

The defensive perimeter established by Beauregard followed the plans of General

Lee to place the inland defenses out of range of the heavy naval batteries. The abandonment of Cole's Island by General Pemberton

opened the Stone River to the Federal gunboats, and allowed for an amphibious attack on James Island and Morris Island. Beauregard

recognized James Island as the key to the siege and emphasized the defenses on the island accordingly. The Federal assault

on the city lasted from l863 to l865, involving nearly continuous naval bombardment. Beauregard‘s defenses were able

to resist the Federal attack until the advance of General Sherman demanded the abandonment of the city.

Charleston, South Carolina, ushered onto the world stage a new ere of warfare.

Coastal masonry fortifications were no longer citadels of peace, because rifled-artillery

made them obsolete structures that had been born out of paranoia and excess. Primitive earthworks proved to be bastions

of resilience, until the siege and mortar guns worked in concert to subdue them. Inventions and innovations employed

in the Charleston area during the Civil War had ushered onto the world stage a new era of warfare.

From 1861 to 1865, the nations had witnessed in the Charleston area the

employment of the multi-personnel submarine as well as ironclads in combat, technological improvements in mines and torpedoes, heavily

constructed platforms in marshes and swamps supporting 8-ton artillery guns as they engaged in siege warfare, siege

trains commandeering behemoth artillery pieces with ease, and determined, yet hastily constructed mosquito fleets unleash

havoc on a naval power.

See also

Sources: Library of Congress, National Archives, National Park Service, Official Records of the

Union and Confederate Armies, Civil War Trust online civilwartrust.org; Burton, E. Milby. The

Siege of Charleston, 1861-1865. Columbia, University of South Carolina Press, 1972; Coulter, E. Merton. The Confederate

States of America, 1861-1865. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1950; Freeman, Douglas Southall. R.E. Lee,

A Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1934; Gillmore, Q.A. Engineer and Artillery Operations Against the Defenses

of Charleston Harbor in 1863. New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1865; Supplementary Report to Engineer and Artillery Operations

Against the Defenses of Charleston Harbor in 1863. New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1868; Hagood, Johnson. Memoirs of the War

of Secession. Columbia, S.C.: The State Co. 1910; Johnson, John. The Defense of Charleston Harbor. Charleston, S.C.:

Walker, Evans and Cogswell Co. 1890; Jones, Samuel. The Siege of Charleston. New York: Neale Publishing Co., 1911; Mahan,

D.H. A Treatise on Field Fortification. New York: John Wiley, 1860; Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies

in the War of the Rebellion, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1882; Official Records of the Union and Confederate

Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series 1, Vol. 16. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1903; Ripley,

R.J. “Charleston and Its Defenses" in Year Book - 1885, City of Charleston. 1885; Ripley, Warren. Artillery and

Ammunition of the Civil War. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co. 1975; Roman, Alfred. The Military Operations of General

Beauregard. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1884; Simons, Grange. "List of Fortifications of James Island and for Whom Named."

Charleston, S.C. Washington Light Infantry Collection, Charleston; Whitelaw, Robert N. S. and Alice F. Levkoff. Charleston

Come Hell or High Water; Columbia, S.C.: R.L. Bryan Co., 1975.

Return to American Civil War Homepage

|

|

|